Japan-Malaysia Cooperation in the New Security Landscape of the Indo-Pacific

Sumathy Permal (Maritime Institute of Malaysia) argues there is room to enhance the strategic direction and scope of cooperation between the Japan and Malaysia and that, given the major security challenges and the role of Japan in balancing changing power relations in the Indo-Pacific, Japan and Malaysia should focus on increasing security cooperation in order to address challenges arising from strategic changes in the maritime domain.

The year 2017 marks the 60th anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic relations between Malaysia and Japan. Relations between the two countries have remained robust since Malaysia’s adoption of its “Look East policy” in the 1980s, which has sent thousands of Malaysian students to receive education and training in Japan. In addition, Japan has contributed to safety of navigation initiatives in the Strait of Malacca since the early 1970s and participated in regional and international efforts to combat piracy and armed robberies at sea.

Japan has also been keen on promoting cooperation in other areas such as maritime security, peacekeeping, and humanitarian assistance and disaster relief. In 2015, Japan and Malaysia concluded an agreement to enhance relations through a strategic partnership to promote peace and stability, economic development, maritime security, people-to-people ties, and regional and global cooperation on issues such as search and rescue, peacekeeping through the UN Development Programme, and the security of sea lines of communications. More recently, they stepped up cooperation on law enforcement at sea after Malaysia’s coast guard received a second patrol vessel from Japan.

A Malaysian Police Special Forces Unit rappels down a Eurocopter AS355 chopper onto the Japanese Coast Guard ship Yashima during a joint anti-piracy exercise off western Thailand, February 2, 2007. (Tengku Bahar/AFP/Getty Images)

Together with the continuation of various forms of ad hoc cooperation, however, there is room to enhance the strategic direction and scope of cooperation between the two countries. Given the major security challenges and the role of Japan in balancing changing power relations in the Indo-Pacific, Japan and Malaysia should focus on increasing security cooperation in order to address challenges arising from strategic changes in the maritime domain.

THE NEW LANDSCAPE AS SEEN FROM KUALA LAMPUR

A key challenge is that growing naval capabilities among the militaries in Asia, and particularly in Southeast Asia, could generate regional instability in the mid to long term. Another is to ensure that the safety and security of sea lanes in the Strait of Malacca and environmental protections in the South China Sea are not compromised. Malaysia, as a littoral state, and Japan, as a major user of the Malacca Strait, will need to evaluate the impact of new forms of traditional and nontraditional threats in the strait as well as assess the need for regional countries to cooperate in preserving the safety, security, and well-being of the region. A third challenge is to ensure that the principles of international law are upheld in the maritime domain. Recent years have seen many threats to international norms and commonly agreed-on principles due to the heightened interests of the various stakeholders in the region. Japan and Malaysia, together with their Southeast Asian friends, can provide ideas and initiatives on how countries with territorial disputes can uphold the rule of law without comprising their respective national interests.

In 2017, notable changes have also occurred in the geopolitical and geostrategic landscape, where global issues have both a direct and an indirect impact on the Indo-Pacific. The shifting positions of the new U.S. administration, developments in Europe and the United Kingdom, and the threat posed by North Korean nuclear and missile tests all pose major challenges. Given this backdrop, countries in Southeast Asia are searching for new strategies to cope with changing scenarios. Some countries have adopted a mid-term approach of playing it safe in global affairs, while others are seeking long-term strategies of embracing new powers by aligning national interests to jointly address the challenges arising from dynamic changes taking shape in Asia that will have significant political, economic, strategic, technological, and cultural impacts on future maritime cooperation.

Malaysia, in this respect, has not made major changes to its approach toward major-power relations. Instead, it is adjusting itself to the changing dynamics by adopting new initiatives on maritime activities on a higher strategic and operational level. Recent efforts in this direction include an exchange of opinions on defense cooperation and exchanges between Japan’s ambassador to Malaysia, Makio Miyagawa, and Malaysia’s minister of defense, Hishammuddin Hussein, in May 2017. On September 13, 2017, Prime Minister Najib Razak and President Donald Trump issued a joint statement on issues concerning the South China Sea, which emphasized the obligation to uphold a rules-based maritime order, avoiding the use of force, intimidation, and coercion. The leaders also called on disputing parties to avoid militarization and other activities that could increase tension in the South China Sea. Although the joint statement reflects Malaysia’s general approach to the South China Sea, it gains special significance in light of the territorial disputes, particularly after the ruling of the Permanent Court of Arbitration in July 2016.

China’s claims in the South China Sea remain a strategic threat for other claimants, as the People’s Liberation Army has declared that “China always remains vigilant and keeps effective surveillance over the military activities of the related countries in the South China Sea,” and that “the Chinese military will resolutely safeguard national sovereignty and security.” This strong position underscores China’s interests in enforcing its territorial claims in the South China Sea. Although a strategic partnership with the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) remains in the cards as long as China tries to derive synergies from the interaction of its Belt and Road Initiative and ASEAN’s integration and connectivity programs, tensions from overlapping claims may be an obstacle to achieving many of the proposed cooperative initiatives. The flare-up in June 2017 between China and Vietnam driven by their maritime dispute is a case in point. The most pressing issue for ASEAN-China cooperation in the South China Sea is the negotiation of a code of conduct (CoC), which is expected to be finalized by the end of 2017. What is yet to be seen is how the CoC will operate in practice and contribute to the avoidance of dangerous encounters at sea.

In this regard, ASEAN, China, and interested parties such as Japan should continue efforts to promote energy connectivity, energy security, accessibility, and sustainability of the use of the sea for all. To those ends, since 1969, Japan has been a primary contributor to the maintenance and improvement of safety of navigation in the Strait of Malacca through its participation in the Malacca Strait Council. That contribution continues: Japan and littoral states are starting a joint hydrographic survey in 2017–20. Perhaps a joint effort of this type to promote maritime safety and security could be considered in the littoral areas of the South China Sea.

FUTURE COOPERATION BETWEEN MALAYSIA AND JAPAN

Japan is an important strategic partner to many Southeast Asian countries, and Malaysia in particular is cognizant of the policy direction of Tokyo, which emphasizes the “importance of maintaining peace, security and stability, freedom of navigation in and over-flight above the South China Sea while reiterating the principles of non-militarization.” This strategic direction provides some level of comfort in ensuring that peace and stability are maintained and that the balance of power remains somewhat manageable in the Indo-Pacific. In this regard, bilateral efforts will continue to be focused on shaping security cooperation in the region and enhancing maritime security, safety of navigation, maritime transportation, and environmental protection, as well as facilitating an exchange of dialogue on issues of common interest.

Foreign ministers from ASEAN, South Korea, Japan, and China join hands during the 18th ASEAN Plus Three Foreign Ministers’ Meeting in Manila on August 7, 2017. (Mohd Rasfan/AFP/Getty Images)

For example, Japan and Malaysia may need to examine the various consultative initiatives adopted in the East and South China Seas for mitigating conflict in areas with overlapping claims and explore the operational and political scenarios that could challenge the effective implementation of such initiatives. This could provide ideas for moving forward on new mechanisms such as simulation tools for crises and diplomatic and nonmilitary channels. Other measures could include continuing the promotion of dialogue on ensuring rule of law, especially for countries with territorial disputes such as Japan and Malaysia. There are several platforms that leverage Japan-ASEAN relations, such as the East Asia Summit, ASEAN Regional Forum, ASEAN +3, and ASEAN Defence Ministers’ Meeting-Plus, that could be useful forums for bringing these issues to the attention of policy planners and practitioners.

Sumathy Permal is a Fellow and Head of the Centre for the Straits of Malacca at the Maritime Institute of Malaysia.

Download a pdf version of this analysis piece here.

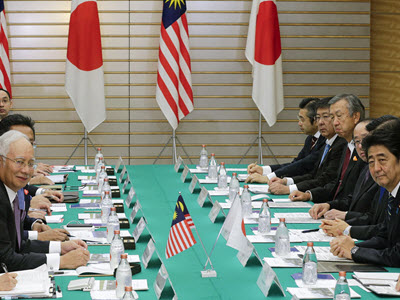

Banner Image: © Kimimasa Mayama/AFP/Getty Images. Malaysian Prime Minister Najib Razak talks with Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe (2nd R) at the start of bilateral talks at the latter’s official residence in Tokyo on November 16, 2016.