Australia and the Quad

A Watering Can or a Hammer?

This commentary is part of the roundtable “Quad Cooperation in the Indo-Pacific: Regional Security Challenges and Prospects for Greater Coordination.”

Any discussion of current geopolitical issues must begin with the two great pillars on which Australia’s strategic situation rests: history and geography. From the earliest days of European settlement, Australia has experienced a deep-seated and unsettling sense of national insecurity. The colony established at Sydney Cove in 1788 struggled to survive and clung desperately to the very edge of a topsy-turvy world where the seasons ran back to front on the calendar, where swans were black, and mammals laid eggs. But more importantly, Australia was a very long way from the “mother country”—or any other potential ally or savior.

Then, just as the new colony began to put down slightly deeper roots, to achieve self-sufficiency and to spread inland during the latter years of the eighteenth century, the country experienced the first of what would become a long history of perceived existential threats (mostly imaginary). These threats were first posed by France, then Spain, and finally by Irish rebels exiled to New South Wales following the Irish rebellion of 1798. In the nineteenth century, France was again perceived to be a threat, then Russia, and ultimately challenges emanating from north Asian countries with much larger populations and military capabilities, which was the beginning of what would become a constant in Australian strategic calculations. Taken together, these all added up to a deep sense of environmental, cultural, and geographic isolation that has in many respects continued through the subsequent centuries of European settlement.

In the twentieth century, the dark shadow that loomed over Australia was cast by imperial Japan. As the century reached middle age, the long-held concerns about Japanese militarism took concrete form. The threat from Japan became very real on February 19, 1942, when the northern Australian city of Darwin was bombed in a raid by 242 Japanese aircraft, resulting in the deaths of at least 235 people. Attacks on northern Australian towns and airfields continued until November 1943, as well as miniature submarine attacks on Newcastle and Sydney. Australian casualties in the Pacific during World War II totaled more than 30,000, with 17,500 of those being killed in action or dying of wounds.[1]

All of these formative national experiences have led Australia to a point of acceptance (reflected in the recent Defence Strategic Review) that it cannot realistically expect to defend its homeland alone and friendless against a major-power adversary. Australia has found in multilateralism and transnational agreements the promise of a variety of deterrents that mean it will never have to do so.

Australia’s Commitment to Multilateralism

Since the creation of the new nation in 1901, Australia’s response to its deep-seated sense of national insecurity has been to seek protection inside larger international groupings. It continues to be an enthusiastic joiner of—indeed advocate for—enhanced multilateral security arrangements. Australia was a founding member of the League of Nations, United Nations, World Trade Organization, Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation, Southeast Asia Treaty Organization Five Power Defence Arrangements, Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) Regional Forum, and Australia, New Zealand and United States Security (ANZUS) Treaty, among others. More recently, it has contributed to a cascading torrent of agreements, treaties, arrangements, and dialogues, including the AUKUS partnership with the United Kingdom and the United States, Partners in the Blue Pacific, Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership, Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, and Indo-Pacific Economic Framework.

Each one of those arrangements forms a series of concentric circles, which has at its hard center the 5-4-3-2-1 countdown of the Five Eyes, the Quad, the trilaterals ANZUS and AUKUS, and the bilateral arrangements with the United States and Japan. In fact, if we consider all those arrangements not as concentric circles but as a Venn diagram, with all the large and small configurations overlapping in their various permutations and combinations, only one flag is hoisted at the intersectional sphere at the center of it all—Australia. Not even the United States sits alongside Australia in this segment since it abandoned the Trans-Pacific Partnership.

Of course, Australia’s history of engagement with the Quad has been, like the curate’s egg, good in parts. The decision by then prime minister Kevin Rudd to withdraw Australia from the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue in 2008 led to the dissolution of the Quad until its resurrection in 2017. Rudd’s decision was the result of a cost-benefit analysis that ranked trade relations with China as being of greater strategic significance than the Quad. That calculus changed irrevocably when China unilaterally imposed a series of rolling trade sanctions on Australian exports beginning in 2020, apparently to punish Australia for a range of offences against China’s national pride. Since then, the Quad has gone from strength to strength with reinvigorated quadripartite naval exercises (Malabar) and an expanded agenda of cooperative international ventures.

The Role of the Quad in Australia’s Geostrategic Calculus

For Australia, the Quad is significant both for what it does and for what it represents. When painting with broad strategic brush strokes, Australia cleaves to the Quad’s oft-repeated aim of maintaining a “free and open Indo-Pacific” (as well as the unstated priority of providing a restorative balance to China’s growing reach and grasp). But on a more granular level, the Quad provides a number of enhancements to Australia’s strategic position.

First, the Quad locates Australia at the center of the Indo-Pacific. Australia’s geography puts the country there. The east-west axis runs from New Delhi to Perth, from Perth to Sydney, and onto Pearl Harbor and Washington; the north-south axis runs from Adelaide (the future location for Australia’s construction program for nuclear-powered submarines) through Darwin and onto Tokyo.

Second, the Quad is an arrangement that connects East and West, global North and global South, and in particular “Indo” and “Pacific.” The Quad frames Australia as an Indo-Pacific nation looking beyond its traditional Anglosphere connections in the Five Eyes partnership and the critical trilateral agreements of AUKUS and ANZUS.

Third, the Quad engages the strategic attention of both India and the United States. It enables India to engage in a manner and at a pace with which New Delhi is comfortable, and there is no “Indo-Pacific” without India. The Quad also ensures that the United States remains focused on the Indo-Pacific even as events in Europe, including Russia’s aggression in Ukraine, threaten to pull its focus away. While countries in Southeast Asia and the Pacific do not wish to be forced to choose between the United States and China, most do not wish to see China with a monopoly on regional power and influence either.

Fourth, the Quad is not a formal, or even an informal, defense pact. The lack of a hard edge has provoked sneering remarks about a “toothless tiger” in some quarters, but its emphasis on the soft-power elements of international strategic policy—ranging from cooperation on pandemic response, emergency planning, and cybersecurity to counterterrorism, maritime domain awareness, and environmental issues—enables the Quad partners, and India in particular, to demonstrate the partnership’s role beyond being a mere strategic counterweight to China. This allows the group to be viewed as a force for building and maintaining partnerships in the contested spaces of the Asia-Pacific.

It is worth reiterating that the Quad is not a formal treaty alliance. Its binding connection rests on its claims to a shared set of values in relation to respect for international law and the critical principles of freedom of navigation, respect for territorial integrity and national sovereignty, and peaceful dispute resolution. The power of the Quad currently rests in its ability to demonstrate to China, as well as other regional partners, that like-minded countries can and will work in concert to push back against the inclination of powerful countries to use coercion rather than cooperation.

In response to the evolution of the Quad, China has expressed concern about the threat the arrangement poses to regional stability and accused the member nations of attempting to build an Indo-Pacific version of NATO to contain China’s legitimate aspirations for regional influence. At the annual Raisina Dialogue in New Delhi, the commander of the U.S. Indo-Pacific Command, Admiral John Aquilino, flatly rejected that claim, though he noted that he expected there would certainly be “increased multilateral events between partners.”[2] It is precisely that “strategic ambiguity” concerning the future of the Quad that worries China. As former secretary of state Michael Pompeo put it, the Quad grouping could be a vehicle “to begin to build out a true security framework,” a “fabric” that can “counter the challenge that the Chinese Communist Party presents to all of us.”[3]

From the Australian perspective, the Quad has also provided a forum within which new bilateral security arrangements have flourished, particularly in relation to Japan. Australia and Japan—countries that the late Japanese prime minister Shinzo Abe described as “neighbours at a longitude of 135 degrees east”—form the north-south anchor points for the Quad.[4] For Japan, the Quad has provided a safe environment in which it can assert a more “forward leaning” international security posture, one which includes a new series of defense arrangements with Australia.

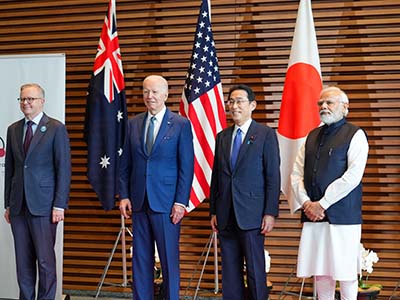

At a meeting in Perth in October 2022, Australian prime minister Anthony Albanese and Japanese prime minister Fumio Kishida released the Joint Declaration on Security Cooperation, which reaffirmed the two countries’ enthusiasm for an enhanced defense and security partnership. Nestled within the broad Quad aspirations restated in the declaration (a “free and open Indo-Pacific region that is inclusive and resilient”) lie harder-edged commitments. The two governments have now agreed to identify ways to “enhance interoperability,” including through an expanded program of military exercises and training exchanges. Building on the Reciprocal Access Agreement signed in January 2022, Japan and Australia are developing programs for increased “defence activities in each other’s territories” and recommitted to “deepening bilateral collaboration in space, cyber, information sharing, and regional capacity-building.”

In the Pacific, that regional capacity building is finding expression in the Partners in the Blue Pacific initiative, which aims to be “an inclusive, informal mechanism to support Pacific priorities more effectively and efficiently” by connecting the small nations of the Pacific to a partnership of larger countries (Australia, the United States, Japan, New Zealand, and the UK) that blends AUKUS, ANZUS, and the Quad (sans India) in a nonthreatening “informal” arrangement.

For Australia, Japan has become an ally in all but name, a key pillar in its regional engagement strategy. For Japan, Australia represents both a valuable strategic partner in its own right, but also a welcome point of entry to AUKUS (pillar two, in particular) and even the Five Eyes intelligence partnership. Both countries have been on the wrong end of Chinese targeted coercion and intimidation, and that is surely no coincidence.

Conclusion

Not every tool in the national security toolbox needs to be able to do the same job. There are times when a watering can is needed, and at other times a hammer. The point is to have a sufficient range of tools available to deal with the variety of national security tasks to be addressed.

The recently released Australian Defence Strategic Review makes the point that the Indo-Pacific is “defined by a large population, unprecedented economic growth, major power competition and an emerging multipolar distribution of power, but without an established regional security architecture.” Could an enhanced Quad provide the basis for that “regional security architecture” to realize Pompeo’s vision of the Quad as a “true security framework”?

That seems an unlikely prospect unless and until India concludes that China poses an unacceptable threat not only to India’s regional sphere of influence in the Bay of Bengal, but to its territorial integrity. So for now the Quad provides a “watering can” for soft-power programs to develop a coherent regional response to China’s regional aggression. But if China overplays its hand, perhaps the Quad could provide a hammer as well.

Mark R. Watson is the Director of the Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI) Office in Washington, D.C.

Endnotes

[1] Gavin Long, The Final Campaigns (Canberra: Australia War Memorial, 1963).

[2] Emma Connors, “NATO a Good Model for Indo-Pacific: U.S. Military Commander,” Australian Financial Review, April 27, 2022, https://www.afr.com/world/asia/nato-a-good-model-for-indo-pacific-us-military-commander-20220427-p5agm4.

[3] Hiroyuki Akita and Eri Sugiura, “Pompeo Aims to ‘Institutionalize’ Quad Ties to Counter China,” Nikkei Asia, October 6, 2020, https://asia.nikkei.com/Editor-s-Picks/Interview/Pompeo-aims-to-institutionalize-Quad-ties-to-counter-China.

[4] Kei Hakata and Brendon J. Cannon, “Stage Is Set for Australia and Japan to Play a Decisive Role in the Indo-Pacific,” Australian Strategic Policy Institute, Strategist, April 3, 2023, https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/stage-is-set-for-australia-and-japan-to-play-a-decisive-role-in-the-indo-pacific.