China-Russia Naval Cooperation in East Asia

Implications for Japan

To what extent does increased China-Russia naval cooperation pose a threat to Japan? Additionally, what has been Japan’s response? This essay addresses these questions and considers the implications for regional stability.

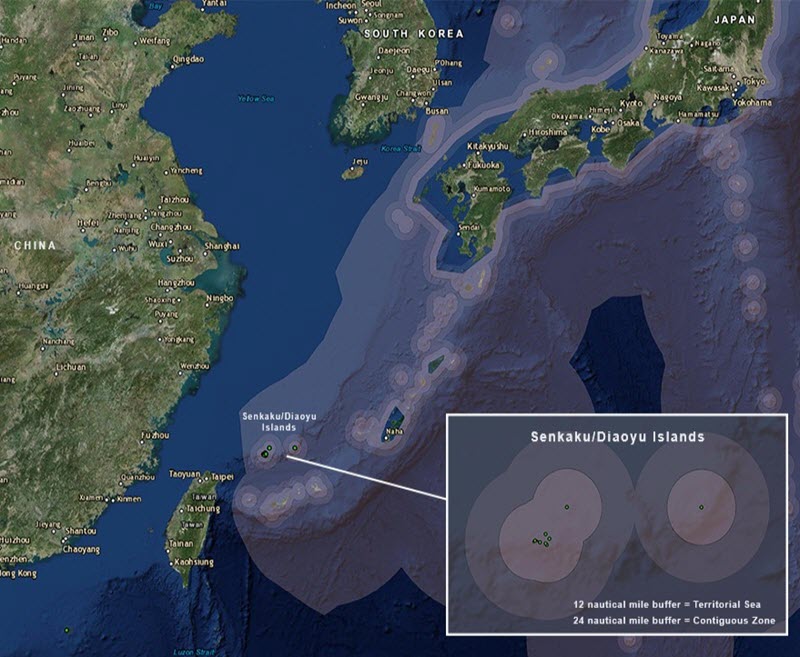

During the evening of June 8, 2016, three Russian naval vessels, including a destroyer, entered the contiguous zone around the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands in the East China Sea. Shortly afterward, a Chinese frigate also entered the area and proceeded toward the Russian ships, as if intending to meet with them. This represented the first instance of a Chinese military vessel entering the contiguous zone around the Japanese-administered Senkaku Islands, which are claimed by China as the Diaoyu Islands. Just as worrying, it appeared to show that Russia, which officially remains neutral with regard to the territorial dispute, had begun to coordinate its actions with China.

Map showing the contiguous zone around the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands where Russian and Chinese naval vessels transited in June 2016. Visit our full Interactive Map.

This incident drew attention to the expanding scale of China-Russia naval activities within East Asia. The centerpiece of this cooperation is Joint Sea, a series of bilateral drills that have been held annually since 2012, including in the Yellow Sea, East China Sea, and South China Sea. Joint Sea 2017 took place in the Sea of Japan and Sea of Okhotsk, with the main focus on submarine rescue and antisubmarine warfare. [1]

According to material provided to the author by the Russian Ministry of Defense, the Joint Sea exercises “are organized on the basis of the principles of relations of strategic partnership between Russia and the People’s Republic of China.” Their overall aim “is to increase mutual trust and understanding between the fleets of the two countries in the interests of the peaceful use of the oceans and to jointly counter threats to maritime security at sea.”

The Russian ministry’s document also specifies that the annual exercises have each included 10 to 25 ships of various classes as well as planes, helicopters, and personnel and equipment from the countries’ marine corps. Each exercise is overseen by a joint command headquarters, which alternates between Russian and Chinese territory. More specifically, the exercises have concentrated on improving interoperability by addressing questions about the organization of communications, as well as by conducting drills in the areas of anti-aircraft and antisubmarine defense, the convoying of ships, search and rescue training, and the freeing of pirated ships.

To what extent does this increased China-Russia naval cooperation pose a threat to Japan? Additionally, what has been Japan’s response? This essay addresses these questions and considers the implications for regional stability.

Staff check on a helicopter before lifting off the amphibious transport dock Kunlun Shan during China-Russia naval drill Joint Sea 2016 on September 17, 2016 in Zhanjiang, Guangdong Province, China. (VCG/Getty Images)

A THREAT TO JAPAN?

Officially, the Russian Ministry of Defense states that naval cooperation with China “is not directed against a third party and is not connected with the political situation in the region.” [2] This claim was not accepted by the interviewees, including former and current members of the Japan Maritime Self-Defense Forces (JMSDF), who were consulted during the preparation of this essay. At the same time, however, the predominant view of these Japan-based experts was that China-Russia naval cooperation does not, at present, represent a leading threat to Japan.

In terms of the motivations driving closer naval ties between China and Russia, the primary factor is considered to be China’s desire to gain access to Russian technology and expertise. This is because, despite the progress made by the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) in recent years, Russia retains a lead in key areas. In particular, Bonji Ohara of the Sasakawa Peace Foundation in Tokyo emphasizes China’s need for Russian assistance to improve the quality and effectiveness of its submarine forces. [3] In terms of the surface fleet, China is moving away from reliance on Russian technology, yet Russia is still seen as having the greater expertise in this area. Emphasizing this point, retired JMSDF vice admiral Fumio Ota states that, while Russia’s naval capabilities may have declined since 1991, its knowledge base regarding operations has been retained and will be of value to China. [4] He also points to the Russian Navy’s firing of cruise missiles from the Caspian Sea to strike Islamic State targets in Syria in October 2015 as an example of Russia’s impressive expertise and combat experience.

In addition to these operational factors, China-Russia naval cooperation is judged to be motivated by broader strategic considerations. Indeed, Tuan Pham, who is a strategic planner for the U.S. Navy but was speaking in a personal capacity, makes the point that China-Russia naval exercises have greater political than operational significance. [5] According to this line of thinking, China and Russia have been pushed together by shared tensions with the United States, and the naval drills are therefore a symbolic means of demonstrating their common stance against U.S. pressure. Making a similar point, retired JMSDF vice admiral Yoji Koda describes the joint exercises as “psychological warfare” by Russia. That is, they are a means for Moscow to signal to Washington what will happen if U.S. pressure on Russia continues. [6] For this same reason, Ohara argues that Russia became more enthusiastic about naval cooperation with China after the downturn in relations with the West that followed the outbreak of the Ukraine crisis in 2014.

China and Russia have therefore been brought together by certain shared interests. Yet their capacity to cooperate closely at sea, and thereby pose a potential joint threat to Japan and the U.S.-Japan alliance, remains seriously restricted. In part, this is due to technical factors. For instance, according to Ohara, after having initially considered relying on destroyers of the Russian type, China ultimately opted to prioritize destroyers that have more in common with Western models. Added to this, China’s pursuit of network-centric warfare and the use of its own BeiDou satellite navigation system also make interoperability with Russian forces more difficult.

Such technical issues could be resolved, but a much bigger obstacle is the lack of trust that exists between the two sides. All interviewees made this argument. Some highlighted historical tensions between China and Russia and the prospect that China may one day seek to recover “lost territory” in the Russian Far East. Others pointed to more contemporary factors, arguing that Russia is deeply concerned about China’s growing presence in Central Asia and the Arctic. Ota also claimed that Russia remains suspicious due to China’s record of allegedly stealing Russian military technology. Pham further noted that Moscow and Beijing do not share a common understanding of fundamental issues of maritime law, since Russia accepts the right of a military to conduct activities in a foreign country’s exclusive economic zone, whereas China resolutely does not.

There are several examples that appear to demonstrate this lack of trust. In July 2012, China’s icebreaker, the Xuelong, entered the Sea of Okhotsk without the Chinese authorities having paid the courtesy of informing Russia in advance. [7] This is significant because the Sea of Okhotsk, which is almost entirely surrounded by Russian territory, is of strategic importance due to its use by Russia’s ballistic missile submarines. Additionally, following the Joint Sea drills in the Sea of Japan in July 2013, five Chinese warships did not return directly to their home port but passed through La Pérouse Strait and into the Sea of Okhotsk, marking the first instance of Chinese military vessels entering this body of water. At the same time, Russia ordered snap inspections to be held throughout its Eastern Military District, as well as combat exercises in the Sea of Okhotsk. According to Ohara, Russia’s actions were intended to send the message that Moscow does not welcome China’s presence in these waters. This interpretation is not directly confirmed by Russian sources, though independent Russian media did express misgivings about this unprecedented Chinese action. [8]

A further example is Vostok 2018. This military exercise, which was held in Russia’s eastern regions in September, was presented as a landmark in China-Russia military cooperation since China contributed 3,200 troops, as well as tanks, infantry fighting vehicles, armored personnel carriers, self-propelled artillery, 6 aircraft, and 24 helicopters. Yet this appearance of harmony was disturbed when it was revealed that during the drills China had sent a Dongdiao-class surveillance ship to gather intelligence about Russia’s naval maneuvers. [9]

Chinese troops and military equipment parade at the Vostok 2018 military drills at Tsugol training ground near the Russian border with China and Mongolia on September 13, 2018. (Mladen Antonov/AFP/Getty Images)

These mutual suspicions are viewed as hindering cooperation between the Chinese and Russian fleets. Serving members of the JMSDF, who preferred to remain anonymous, stressed that in terms of interoperability, China and Russia are still at an “early stage” and that their level of cooperation is in no manner comparable to that between Japan and the United States. [10] Pham makes a similar point, arguing that, while the quantity of China-Russia naval activities has increased, the quality in terms of the sophistication of the joint drills remains limited. Illustrating this point, he observes that while the U.S. Navy and JMSDF routinely practice fighting together, China and Russia are still just learning how to sail together.

As for the incident near the Senkaku Islands in June 2016, opinions are varied. Ota takes the view that the Chinese frigate took advantage of the passage of the Russian ships to opportunistically enter the contiguous zone, thereby giving the appearance of coordination. He also stresses that Russia has nothing to gain by abandoning its neutral position on the dispute. However, the serving JMSDF officers interviewed were more mistrustful, noting that the Russian ships had the choice of any number of routes, yet deliberately chose to pass through the islands’ contiguous zone. Overall though, they remain relatively relaxed about the incident, reassured by the fact that, so far, it has been a one-off.

JAPAN’S MARITIME ENGAGEMENT WITH CHINA AND RUSSIA

Although Japanese experts consider China-Russia naval cooperation to be at the early stages of development, Japan evidently cannot ignore the challenges presented by China’s and Russia’s naval activities. First, the serving JMSDF officers candidly stated that they trust neither country. Even if the Chinese and Russian navies do not achieve significant interoperability, each individually represents a capable force. Moreover, as Pham notes, there is the potential for the two countries to simply coordinate their actions in order to conduct diversionary activities aimed at Japan and its U.S. ally.

The increased resources and activities of the PLAN have received ample attention, yet it is worth noting that Russia’s naval capabilities in East Asia have also been upgraded in recent years. This looks set to continue with the announcement in May 2018 that the Pacific Fleet is to receive more than 70 naval ships and support vessels by 2027. [11]

Of more immediate concern to Japan was Russia’s deployment of Bal and Bastion anti-ship missiles to the disputed islands of Kunashir and Iturup (Kunashiri and Etorofu in Japanese) in November 2016. [12] Russia has also been developing infrastructure on Matua. This island, which is situated in the central part of the Kuril chain, was the site of a Japanese military facility until 1945 but is no longer claimed by Japan. The Russian military has been working to reopen the airstrip on Matua for use by light military transport aircraft and helicopters, and there is discussion of the Pacific Fleet basing forces on the island. [13] This would reinforce Russia’s control over the Sea of Okhotsk and increase its ability to project force over the eastern end of the Northern Sea Route.

Japan does therefore need to take account of both Russian and Chinese naval activities in its vicinity. As always, the linchpin of Japan’s security remains close cooperation with the United States. Yet, when it comes to addressing maritime issues with China and Russia, Japan’s approach diverges from that of its main ally. In particular, while the U.S. National Security Strategy of 2017 does nothing to hide the fact that China and Russia are viewed as adversaries, Japan places more emphasis on engagement and confidence building. In justifying this approach, the serving members of the JMSDF emphasized geography, stressing that Japan is surrounded by authoritarian states with which it has no option but to deal. In the words of one officer, “the United States can leave if they want to leave, but Japan cannot leave.” For this reason, Japan has to prioritize “coexistence,” meaning, in this case, the need to pursue at least a certain level of maritime cooperation with China and Russia.

Security engagement has progressed furthest with Russia. This is encouraged by Japan’s National Security Strategy of 2013, which states that “it is critical for Japan to advance cooperation with Russia in all areas, including security and energy, thereby enhancing bilateral relations as a whole.” [14]

In accordance with this goal, Japan has initiated “2+2” meetings with Russia. These bilateral talks, which take place between foreign and defense ministers, have usually been reserved by Japan for countries that are considered close security partners, such as the United States and Australia. The first Japan-Russia 2+2 was conducted in November 2013 and reached agreement, among other things, on establishing navy-to-navy staff talks. There was a pause in these meetings on account of the Ukraine crisis, but the format was resumed in March 2017 and a third meeting was held in July 2018.

These political discussions have been supplemented by reciprocal visits by the heads of the countries’ armed forces. Specifically, General Valerii Gerasimov, the chief of general staff, traveled to Japan in December 2017 in a visit that raised eyebrows in Europe due to his presence on the European Union’s sanctions list for his role in the Ukraine crisis. His counterpart, chief of staff Admiral Katsutoshi Kawano, made a return visit to Russia in October 2018.

Specifically in the maritime realm, Japan and Russia are signees to the long-standing Agreement on Prevention of Incidents at Sea. Since 1998, they have also regularly conducted joint search and rescue exercises. The most recent of these was in July 2018, when three ships of the Russian Pacific Fleet visited Maizuru in Kyoto Prefecture to engage in a training exercise with the JMSDF. It is also common for the countries’ naval vessels to make other port visits, such as in October 2018 when three ships of the Pacific Fleet visited Hakodate in Hokkaido.

These aspects of the Japan-Russia naval relationship have existed for some years, but there are also newer features. For instance, when Admiral Kawano visited Russia in October 2018, he traveled to the Admiralty in St. Petersburg to meet the commander in chief of the Russian Navy, Admiral Vladimir Korolev. The two admirals discussed the continuation of bilateral cooperation to maintain maritime security in the Asia-Pacific, and Admiral Korolev was invited to visit Japan in 2019. Even more strikingly, in November 2018 the JMSDF and Russia’s Northern Fleet conducted their first joint antipiracy exercises in the Gulf of Aden. This drill included Japan and Russia flying helicopters off the decks of each other’s destroyers.

According to Ota, the main reason for Japan’s increased emphasis on cooperation is the aim of drawing Russia away from China, since Japan cannot take the risk of facing two major military threats at the same time. Having said this, none of the interviewees believed that maritime cooperation would proceed beyond a low level of pragmatic interaction. For instance, while flying helicopters off each other’s ships may seem like an impressive level of cooperation, Ohara stresses that it is not difficult since all that is needed is sufficient space.

Serving members of the JMSDF also emphasized that maritime cooperation between Japan and Russia will be limited by a lack of mutual trust. In particular, they highlighted Russia’s announcement of live-fire drills on the disputed Southern Kuril Islands just a matter of hours after the conclusion of Admiral Kawano’s visit to Russia. They described this as indicative of Russia’s tendency to “shake your hand and kick you at the same time.”

Japan’s maritime cooperation with China is even more limited, yet this is not to say that Japan wishes to take a confrontational approach. Instead, even as China is clearly viewed as representing the largest naval threat, Japan continues to seek means of ensuring that maritime tensions do not escalate into crises. This involves establishing a minimal level of shared confidence.

Following the ship collision incident near the Senkaku Islands in September 2010 and the Japanese government’s subsequent nationalization of several of the islands in 2012, even the most modest forms of maritime cooperation between Japan and China proved impossible. Yet, as the political atmosphere has gradually improved since 2017, talks about confidence-building mechanisms at sea have been revived. Most significantly, during Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s visit to Beijing in October 2018, the two sides agreed on the importance of making concrete progress in the area of maritime security. Specifically, they announced the first annual meeting of the Maritime and Aerial Communication Mechanism between their defense authorities. The sides also signed a maritime search-and-rescue agreement. Additionally, they agreed to promote reciprocal visits by the defense ministers as well as to conduct further exchanges between the defense authorities and reciprocal port visits by naval vessels. [15] In line with this agreement, Japan will send a destroyer to China in April 2019 to join a fleet review marking the 70th anniversary of the founding of the PLAN. [16] This will be the first JMSDF vessel to visit China in over seven years.

These efforts are not expected to fundamentally change the nature of the strategic relationship between Japan and China. It is hoped, however, that they will help bring a degree of stability and predictability to maritime interactions.

CONCLUSION

Overall, while China-Russia naval cooperation in East Asia has grown in prominence in recent years, the countries are still regarded as being in the early stages of their relationship. As such, they are not currently judged to represent a joint maritime threat to Japan or the U.S.-Japan alliance. What is more, given the level of mistrust that is assumed to prevail between China and Russia, this situation is not expected to change in the short term.

This lack of interoperability does not change the fact that China and Russia individually possess naval forces that can challenge Japan’s interests in the region. However, rather than taking a directly confrontational approach to these perceived threats, Japan has prioritized “coexistence.” This has entailed developing a basic level of maritime cooperation with both countries, especially with Russia. In this way, Japan is seeking to guarantee stability in its maritime vicinity, while also looking to ensure that the superficial level of naval cooperation that currently exists between China and Russia does not develop into something more strategically significant over time.

James D.J. Brown is an Associate Professor at Temple University’s Japan Campus in Tokyo.

Download a pdf version of this analysis piece here.

Endnotes

[1] “Vuchenii ‘Morskoye vzaimodeystviye–2017’ budet zadeystvovano 11 korabley VMF Rossii i VMS Kitaya” [11 Ships from the Russian and Chinese Navies to Cooperate in “Joint Sea 2017” Exercises], Ministry of Defense (Russia), September 17, 2017, https://function.mil.ru/news_page/country/more.htm?id=12142569@egNews.

[2] “V Novorossiyske otkrylis’ ucheniya RF i KNR ‘Morskoye vzaimodeystviye–2015’” [“Joint Sea 2015” Exercises between Russia and China Opened in Novorossiysk], TASS, March 11, 2015, https://tass.ru/armiya-i-opk/1960989.

[3] Author’s interview with Bonji Ohara, senior fellow at Sasakawa Peace Foundation, Tokyo, November 12, 2018.

[4] Author’s interview with Fumio Ota, a retired JMSDF vice admiral, Tokyo, November 5, 2018.

[5] Author’s interview with Tuan Pham, U.S. Navy strategic planner, Yokohama, November 5, 2018.

[6] Author’s interview with Yoji Koda, a retired JMSDF vice admiral, Tokyo, November 30, 2018.

[7] Mihoko Kato, “Japan and Russia at the Beginning of the Twenty-First Century: New Dimension to Maritime Security Surrounding the ‘Kuril Islands,’” Research Unit on International Security and Cooperation (UNISCI), UNISCI Discussion Paper, no. 32, May 2013.

[8] Vasilii Golovnin, “Kitayskiy flot vyshel v Okhotskoye more” [Chinese Navy Enters Sea of Okhotsk], Echo of Moscow, July 25, 2013, https://echo.msk.ru/blog/golovnin/1122382-echo.

[9] Sam LaGrone, “China Sent Uninvited Spy Ship to Russian Vostok 2018 Exercise Alongside Troops, Tanks,” U.S Naval Institute, USNI News, September 17, 2018, https://news.usni.org/2018/09/17/china-sent-uninvited-spy-ship-russian-vostok-2018-exercise-alongside-troops-tanks.

[10] Author’s interview with members of JMSDF, Tokyo, October 25, 2018.

[11] “Tikhookeanskiy flot poluchit boleye 70 korabley i sudov k 2027 godu” [Pacific Fleet to Receive More than 70 Naval and Other Ships by 2027], RIA Novosti, May 21, 2018, https://ria.ru/20180521/1520967307.html.

[12] Aleksei Ramm and Nikolai Surkov, “Rossiya razmestila na Kurilakh sverkhzvukovyye ‘Bastiony’” [Russia Has Deployed Supersonic ‘Bastions’ on the Kurils], Izvestia, November 22, 2016, https://iz.ru/news/646043.

[13] Kurokawa Nobuo, “Chishima retto de Roshia ga kanshin yoseru matoua shima” [Russia Shows Interest in Matua Island in the Kuril Chain], Sankei Shinbun, July 19, 2017, https://www.sankei.com/world/news/170719/wor1707190025-n1.html.

[14] National Security Strategy (Tokyo, December 17, 2013), https://www.cas.go.jp/jp/siryou/131217anzenhoshou/nss-e.pdf.

[15] “Prime Minister Abe Visits China,” Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Japan), October 26, 2018, https://www.mofa.go.jp/a_o/c_m1/cn/page3e_000958.html

[16] “Japan to Send SDF Vessel to China Fleet Review,” NHK, March 8, 2019, https://www3.nhk.or.jp/nhkworld/en/news/20190308_17.

Banner Image: © Japan Pool/AFP/Getty Images. This photo taken on October 13, 2011 shows a P-3C patrol plane of the Japan Maritime Self-Defense Forces flying over the disputed East China Sea islets known as the Senkaku Islands in Japan and the Diaoyu Islands in Chin