Commentary from People's Liberation Army Conference

China’s Police Security in the Pacific Islands

Peter Connolly examines China’s use of police advisers to advance its grand strategy in the Pacific Islands and identifies several important implications for policymakers.

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) has delivered its grand strategy in the Pacific Islands with comprehensive whole-of-nation statecraft to increase its geopolitical influence, develop geostrategic access, and accumulate resources since 2017.[1] To achieve these objectives, it has actively employed security statecraft (both military and police) to develop its access, presence, and posture in the Pacific Islands through competition short of conflict. China uses internal security means to project security statecraft in areas of nontraditional security—a technique for which most Western countries are not well equipped to compete.[2] This commentary examines the growing phenomenon of Chinese police advisers in the Pacific Islands.[3]

A New Security Strategy

The PRC is employing police to pursue its security interests in Pacific Island countries, particularly those that do not have a military. This has several important implications for policymakers. Deployed PRC Ministry of Public Security police advisers are executors of China’s strategic intent. They should be considered part of a holistic security system, along with the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), China Coast Guard, and People’s Armed Police. A police presence is more easily normalized than a military one, can affect the local rule of law, and can generate greater influence and access within the host nation. Furthermore, the expansion of China’s police assistance could exacerbate unrest or cede sovereignty to the PRC. Finally, civil unrest and climate-related crises could also be used as vectors for Chinese security statecraft.

China’s Military Strategy, the PRC’s 2015 defense white paper, directed two new tasks: to secure overseas interests and to conduct security cooperation with foreign security forces. The broader agenda for security was then embraced by the PRC and coordinated by the National Security Commission in accordance with Xi Jinping’s comprehensive national security concept. This approach combined the 2006 policy of “overseas citizen protection” with the need to secure the PRC’s expanding overseas assets under the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) using all means available. Such integration of statecraft was then enabled by legislation demanding civil-military integration under the new coordinating power of ambassadors in-country.[4] Protection of interests and security cooperation were incorporated into nonmilitary security statecraft, formalized by the PRC’s Global Security Initiative of 2023.[5] The concept paper for the initiative observes that “traditional and non-traditional security threats have become intertwined” and identifies the Pacific Island countries as potentially in need of the PRC’s nontraditional security cooperation.[6] China has employed internal security means to project security statecraft in areas of nontraditional security with ease.[7]

PRC Police in the Pacific

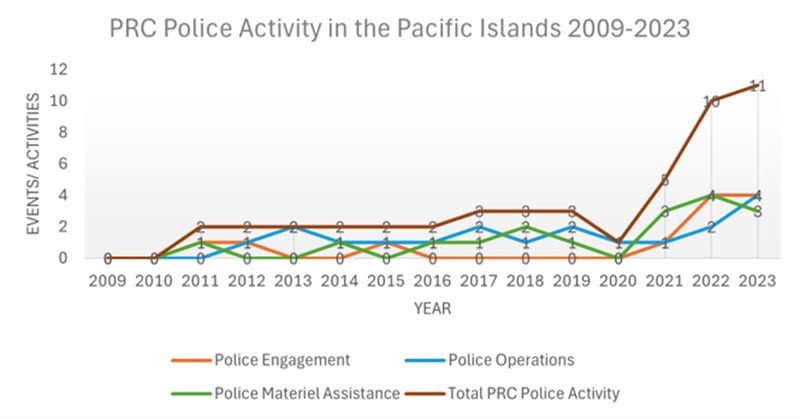

It could be argued that advisers from China’s police forces are more effective than their military counterparts at engaging and influencing the elite, law enforcement, the Chinese diaspora, and the grassroots population in a developing country. In a state with no military, police advisers are often the only means for delivering security statecraft. China’s police presence in the Pacific has attracted attention in the last two years but started quietly a decade earlier (see Figure 1), with China and Fiji signing a memorandum of understanding in 2011.[8]

Source: Figure 1 is based on a timeline of open-source events in the Pacific from 2009 to 2023 compiled by the author. Each event is recorded with a single unweighted value in a given year.

This agreement instituted an annual six-month police exchange, through which senior provincial police were embedded with the Fiji Police Force, while Fijians were trained in China.[9] This relationship enabled several extraditions of Chinese suspects from Fiji, including a sizable “joint” operation in Nadi in 2017.[10] The PRC’s first permanent police adviser in the Pacific was Lu Lingzhen, who was appointed the police liaison officer for Suva in September 2021.[11] This permanent police presence in Fiji established a precedent for police advisers to deliver security statecraft in Pacific nations that did not have militaries. However, the police relationship was called into question when Sitiveni Rabuka was elected prime minister in 2023.

77 alleged “cyber fraud” suspects extradited by PRC Ministry of Public Security police from Nadi (Fiji) to Changchun (PRC) on August 5, 2017. (Xinhua / Alamy Stock Photo)

The November 2021 riots in Honiara, the capital of Solomon Islands, presented an opportunity for the PRC’s police, who were on the ground within two months. The PRC had initially been prevented from sending an armed security detachment to protect its embassy but succeeded in deploying a China–Solomon Islands police liaison team of nine on January 26, 2022.[12] The team, originally pledged as two officers to conduct training for three months, started as nine and grew to twelve over a series of four six-month rotations. It then doubled in size for the Pacific Games in October 2023.[13] The police liaison team presented equipment, signed a police-to-police memorandum of understanding with the Royal Solomon Islands Police Force (RSIPF), and began a series of courses for the RSIPF. In March 2022 a draft security framework agreement stated that “China may, according to its own needs,” replenish and transition military forces through Solomon Islands “to protect the safety of Chinese personnel and major projects in Solomon Islands.”[14]

Solomon Islands Prime Minister Manasseh Sogavare (L) looks on with Li Ming (2nd R), China’s ambassador to the Solomon Islands, as they listen to a Chinese police officer (R) during a ceremony in Honiara on November 4, 2022. (Gina Maka/AFP via Getty Images)

During the police liaison team’s first six months on the ground, the security framework agreement demonstrated the potential to increase domestic tensions rather than alleviate them. A potential rift developed between RSIPF elements trained by Australian police and Chinese police.[15] This concern remains apparent in 2024, exacerbated by reports of a large shipment of weapons illegally imported by the PRC embassy in 2022.[16] The fifth rotation of the police liaison team is now in Honiara, and the contingent was increased to 30 personnel for the National General Elections in 2024.[17] A public letter from officers of the RSIPF posted on X on May 9, 2024, claimed that the Solomon Islands police liaison team had transferred additional Chinese police from Kiribati and Vanuatu to bolster the PRC security for the country’s elections without the knowledge of the Solomons Islands government. Naturally this account was denied by the RSIPF hierarchy, which was criticized in the letter.[18] The potential for friction within Solomon Islands’ only security force is a sensitive topic given the memory of the “tensions” (1998–2003).

Police cooperation was discussed with the PRC’s Pacific Island BRI partners during the mid-2022 regional tour by Foreign Minister Wang Yi.[19] Kiribati and Vanuatu then received “scoping visits” from the Ministry of Public Security. Commissioner Li Tongde’s contingent arrived in Tarawa, Kiribati, in July 2023, followed by Shie Jilie’s team in Port Vila, Vanuatu, in August 2023.[20] These contingents are following the Solomon Islands model—starting with a similar size and nature, the teams rotated with fresh personnel in early 2024 and appear to be there to stay.[21]

The Ministry of Public Security deployments in the Pacific Islands have demonstrated the advantages of using police instead of military resources to deliver security statecraft. To strategists in the West, police deployments may seem less confrontational, and for this reason PRC police are a lower-profiled vector for achieving the same strategic goals. This has led to a broader phenomenon in which China provides internal security, while other partners (particularly the United States) provide external security for the same country.[22] Police can gather intelligence, understand security needs, deliver information operations to shape the narrative, support elite capture or regime survival, and normalize authoritarian political control over law enforcement. Other PRC internal security agencies are also likely to provide security cooperation in the Pacific Islands. An African commentator noted the “uncritical application of China’s model of absolute party control could undermine military and police professionalism and the idea of security for all citizens,” posing a risk to human rights.[23]

Pacific Agency

However, statecraft is not a one-way street. The senior officials I have met in Papua New Guinea (PNG), Timor-Leste, Fiji, Vanuatu, and Solomon Islands over the last decade have been cautious and clear-eyed when considering their national interests in relation to external powers. After the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) Summit in 2018, one senior PNG official explained that “BRI follows a similar pattern to Japanese military expansion, but Chinese expansion uses economic methods to seek control.”[24] There was a similar awareness in Fiji based on its relationship with China in the previous decade. A Fijian security official explained: “They want to secure a foothold over here in the Pacific, and they failed in Vanuatu, so what’s the next best option?” Fiji chose to pursue an Australian offer to fund the Blackrock training camp instead. At the inception of the “switch,” a Solomon Islands official predicted the relationship with the PRC would place the country at the “fault line of U.S.-China geopolitical competition,” and it has. Most states find BRI economically attractive but hedge strategically in response to geopolitical competition.

Before Wang Yi’s 2022 regional tour, the PRC circulated a draft joint communique and a five-year action plan proposing the integration of political, economic, and security cooperation between ten Pacific states and China. The president of the Federated States of Micronesia, David Panuelo, observed that the document sought to “acquire access and control of our region.”[25] China’s Common Development Vision was not ratified, but police cooperation remained on the agenda in bilateral discussions. China’s subsequent position paper proposed a disaster management cooperation center, emergency supply reserves, and sub-reserves in the Pacific Islands.[26] In February 2023 the China–Pacific Island Countries Center for Disaster Risk Reduction Cooperation was opened in Jiangmen, Guangdong Province, and sub-reserves arrived in Vanuatu on a PLA Navy amphibious ship in April. These initiatives could be an alternate vector for security statecraft as China’s police relationships grow with Pacific Island countries.

Since then, PNG has sought to separate China’s security initiatives from a strong economic relationship, signing a status of forces agreement with the United States in May 2023 and a bilateral security agreement with Australia in December. China sought a policing and security agreement with PNG in September 2023, and it subsequently used the risk to overseas Chinese caused by riots across PNG’s major population center as a pretext for such an arrangement.[27] Prime Minister Rabuka cut Fiji’s police relationship with China, explaining that “our system of democracy and justice systems are different, so we will go back to those that have similar systems with us.”[28] When the second Ministerial Dialogue on Police Capacity Building and Cooperation between China and Pacific Island countries was held in Beijing at the end of the year, Fiji did not send a representative.[29] Although Fiji eventually restored the policing relationship after a thirteen-month review, the minister responsible stated that no Chinese police would be embedded with the Fiji Police Force, as they had been from 2012 to 2022.[30] This sentiment was echoed less diplomatically by the RSIPF public letter from May 9, 2024, which states: “To the Chinese officers who have broken our laws, we remind them that we only welcome respectful cooperation with China…. We will not be pushed around.”

Perhaps of greater significance than state-level pushback in the Pacific is the interest-based response at subnational levels. In particular, pushback at the grassroots level can occur when a strong local community chooses to evict Chinese small businesses or creates laws to protect the microeconomy from domination by Chinese interests. This is a localized form of protecting interests where tribal power structures could resort to force in securing livelihoods and customary land. Such agency at the local level is often misunderstood by external actors and is likely to result in violence if handled poorly. However, the prospect of unrest is increasingly being employed as an opportunity for China’s security statecraft and a vector of Chinese law-enforcement support. This invites greater risk of instability, which is not in the national interest of the host nation but could be in the interest of a small elite.

Conclusion

The PRC has actively employed security resources to pursue strategic objectives in the Pacific Islands. A key adaptation that all stakeholders should recognize is the significant and growing role of police forces as part of China’s security statecraft in the Pacific. Nations with no military that rely on their police force for national security are most susceptible to this influence. The PRC offers its internal security forces to Pacific Island states as a “public good,” and they have become China’s weapon of choice for competing in the gray zone of the Pacific Islands. It is important that all states recognize this reality to avoid “losing without fighting.”

The PRC has found that its police adviser contingents are more capable of influencing local authorities, maintaining a persistent presence, and propagating China’s narrative to the population on the ground. By offering a means to support regimes against instability (which frequently involves grassroots anti-China sentiment), police liaison teams are the more natural security instrument for PRC political and economic statecraft in Pacific countries, particularly within the framework of BRI and the rationale of the Global Security Initiative. Nonetheless, recent developments have demonstrated that the governments and people of the Pacific Island states have the ultimate say in whether China’s police advisers are welcome in their country.

Peter Connolly is an Adjunct Fellow at the University of New South Wales and the Center for Strategic and International Studies. He has 37 years of experience as an officer in the Australian Army and completed a PhD on Chinese statecraft in Melanesia.

Endnotes

[1] Grand strategy is the comprehensive employment of statecraft to achieve long-term national goals, whereas statecraft is the application of national political, economic, or security means to influence other states.

[2] Sheena C. Greitens, “China’s Use of Nontraditional Strategic Landpower in Asia,” Parameters 54, no. 1 (2024): 38, 43.

[3] This commentary draws on the author’s presentation at the 2023 PLA Conference “Preparing for Conflict? The PLA’s Strategy and Posture in a Complex Security Environment,” held in Charlottesville on June 10–11, 2023.

[4] Andrea Ghiselli, Protecting China’s Interests Overseas: Securitization and Foreign Policy (London: Oxford University Press, 2021), 173.

[5] Greitens, “China’s Use of Nontraditional Strategic Landpower in Asia,” 38.

[6] See principle 6 and priority 10 in Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China (PRC), “The Global Security Initiative Concept Paper,” February 21, 2023, https://www.mfa.gov.cn/eng/wjbxw/202302/t20230221_11028348.html.

[7] Sheena Chestnut Greitens and Isaac Kardon, “Playing Both Sides of the U.S.-Chinese Rivalry: Why Countries Get External Security from Washington—and Internal Security from Beijing,” Foreign Affairs, March 15, 2024, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/united-states/playing-both-sides-us-chinese-rivalry.

[8] Kitione Toroca, “Fiji Reinforces Security Relations with China,” Pacific Islands Development Program, Pacific Islands Report, December 4, 2012.

[9] Cameron Hill, “China’s Policing Assistance in the Pacific: A New Era?” Australian Parliament House Library, April 6, 2018, https://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Parliamentary_Departments/Parliamentary_Library/FlagPost/2018/April/china-pacific-police.

[10] “A Joint Statement by the Fiji Police Force and the Embassy of the People’s Republic Of China,” Fiji Sun, August 8, 2017, http://fijisun.com.fj/2017/08/08/a-joint-statement-by-the-fiji-police-force-and-the-embassy-of-the-peoples-republic-of-china.

[11] “Enhancing Collaboration,” Fiji Police Force, Press Release, September 10, 2021, http://www.police.gov.fj/view/1537.

[12] “China Boosts RSIPF,” Solomon Star, February 25, 2022, https://www.solomonstarnews.com/china-boosts-rsipf.

[13] Stephen Dziedzic, “China Sending More Police, Donating Equipment Including Drones to Solomon Islands for Pacific Games,” ABC News (Australia), October 31, 2023, https://www .abc.net.au/news/2023-11-01/china-sending-more-police-to-solomon-islands-for-pacific-games/103048778.

[14] “(Draft) Framework Agreement Between the Government of the People’s Republic of China and the Government of the Solomon Islands on Security Cooperation,” March 24, 2022, available from https://x.com/AnnaPowles/status/1506845794728837120.

[15] Wilson Saeni, “Security Pact Could Split RSIPF,” Solomon Star, April 2, 2022, https://www.solomonstarnews.com/security-pact-could-split-rsipf.

[16] John Power and Erin Hale, “China’s ‘Replica’ Guns for Solomon Islands Likely Real, U.S. Cable Claimed,” Al Jazeera, September 1, 2023, https://www.aljazeera.com/economy/2023/9/1/china-likely-shipped-real-guns-to-solomon-islands-not-replicas-us-claimed.

[17] A copy of document was provided to the author by a Solomon Islands observer.

[18] “Police Denied Letter Published on Media and It Is Misleading,” Solomon Islands government, May 11, 2024, https://solomons.gov.sb/police-denied-letter-published-on-media-and-it-is-misleading.

[19] Hu Yuwei and Bai Yunyi, “China Ready to Boost Kiribati’s Law Enforcement Ability, Unaffected by Hyping of ‘Failed Security Deal’: Envoy,” Global Times, June 1, 2022, https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202206/ 1267096.shtml.

[20] “Ambassador Zhou Limin Attended the Handover Ceremony of China’s Aid to the Police in Kiribati,” Embassy of the PRC in the Republic of Kiribati, November 27, 2023, http://ki.china-embassy.gov.cn/sgdt/202311/t20231129_11189071.htm; and “Ambassador to Vanuatu Li Minggang Attended the Launching Ceremony of the First Batch of China’s Police Experts,” Embassy of the PRC in Vanuatu, August 25, 2023, http://vu.china-embassy.gov.cn/ sgxx_132387/sgxw_132388/202308/t20230825_11132730.htm.

[21] Kirsty Needham, “Exclusive: Chinese Police Work in Kiribati, Hawaii’s Pacific Neighbour,” Reuters, February 23, 2024, https://www.reuters.com/world/china/chinese-police-work-kiribati-hawaiis-pacific-neighbour-2024-02-23.

[22] Greitens and Kardon, “Playing Both Sides of the U.S.-Chinese Rivalry”.

[23] Paul Nantulya, “China’s Policing Models Make Inroads in Africa,” Africa Center for Strategic Studies, May 22, 2023, https://africacenter.org/spotlight/chinas-policing-models-make-inroads-in-africa.

[24] Quotes in this paragraph are from the author’s interviews in 2019–21.

[25] Letter from President David W. Panuelo to Pacific Island leaders, May 20, 2022, 3, published in Stephen Dziedzic, “China Seeks Region-Wide Pacific Islands Agreement, Federated States of Micronesia Decry Draft as Threatening ‘Regional Stability,’” ABC News (Australia), May 25, 2022, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2022-05-25/china-seeks-pacific-islands-policing-security-cooperation/101099978.

[26] Ministry of Foreign Affairs (PRC), “China’s Position Paper on Mutual Respect and Common Development with Pacific Island Countries,” May 30, 2022, https://www.mfa.gov.cn/mfa_eng/zxxx_662805/202205/t20220531_10694923.html.

[27] Kirsty Needham, “China, Papua New Guinea in Talks on Policing, Security Cooperation—Minister,” Reuters, January 39, 2024, https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/china-papua-new-guinea-talks-policing-security-cooperation-minister-2024-01-29; and Ben Westcott, “China Urges Papua New Guinea to Protect Its Citizens after Riots,” Bloomberg, January 12, 2024, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2024-01-12/china-urges-papua-new-guinea-to-protect-its-citizens-after-riots.

[28] “‘Our Systems Differ’: Fiji PM Rabuka Ends MoU with China, Asks Chinese Cops to Return,” News18.com, January 28, 2023, https://www.news18.com/news/world/our-systems-differ-fiji-pm-rabuka-ends-mou-with-china-asks-chinese-cops-to-return-6929335.html.

[29] Stephen Dziedzic, “Pacific Island Police Ministers, Delegates Enter High-Level Security Talks with China in Beijing,” ABC News (Australia), December 11, 2023, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2023-12-11/pacific-islands-police-ministers-security-talks-beijing/103213960.

[30] Ivamere Nataro, “Fiji to Stick with China Police Deal after Review, Home Affairs Minister Says,” Guardian, March 15, 2024, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2024/mar/15/fiji-china-police-exchange-intelligence-deal.