Forecasting the South China Sea Arbitration Merits Award

Prediction is difficult—especially about the future. Niels Bohr’s words ring true when it comes to the case brought by the Philippines against the People’s Republic of China over their differences in the South China Sea. It is with caution, then, that this analysis forecasts the minimum findings likely to be reached by the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) in its decision on the merits in this case under Annex VII of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). The PCA decision in the jurisdictional phase of the proceedings, delivered last year, was refreshing in its straightforward legal simplicity. This approach suggests that in the merits phase of the case the court will once again ignore political and strategic factors and apply legal doctrine to the facts in the case. Thus, the legal decision will be reached in a vacuum devoid of the usual elements that make the issues in the South China Sea so vexing—the disparity of power between the Philippines and China, the hope of integrating China into a liberal order, and China’s intractable persistence in harnessing economic and political power to change the strategic balance in its favor.

China’s maritime claims are so audacious and disconnected from long-standing norms of customary international law and the text of UNCLOS that we should expect the PCA to deliver a “death blow” to Beijing’s efforts to create legal ambiguity and upend existing law. The arbitration decision will be legally binding on the Philippines and China and will provide guideposts for other states in the region. Since both states are members of UNCLOS, each has a duty to comply with the ruling under Part XV concerning mandatory dispute resolution. Other states will use the decision to assess the strengths of their own claims and to challenge opposing claims, especially China’s. The unanimous decision on award of jurisdiction by the tribunal suggests that the members will strive for agreement on the merits. While this process tends to reduce decisions to the lowest common denominator, it also strengthens the rule of law by avoiding split decisions that could generate controversy and dilute the authority of the court’s opinion. And while the case will be resolved over legal technicalities, it will produce strategic ramifications. A loss by China would further isolate it diplomatically and embolden other states to stand up to Beijing.

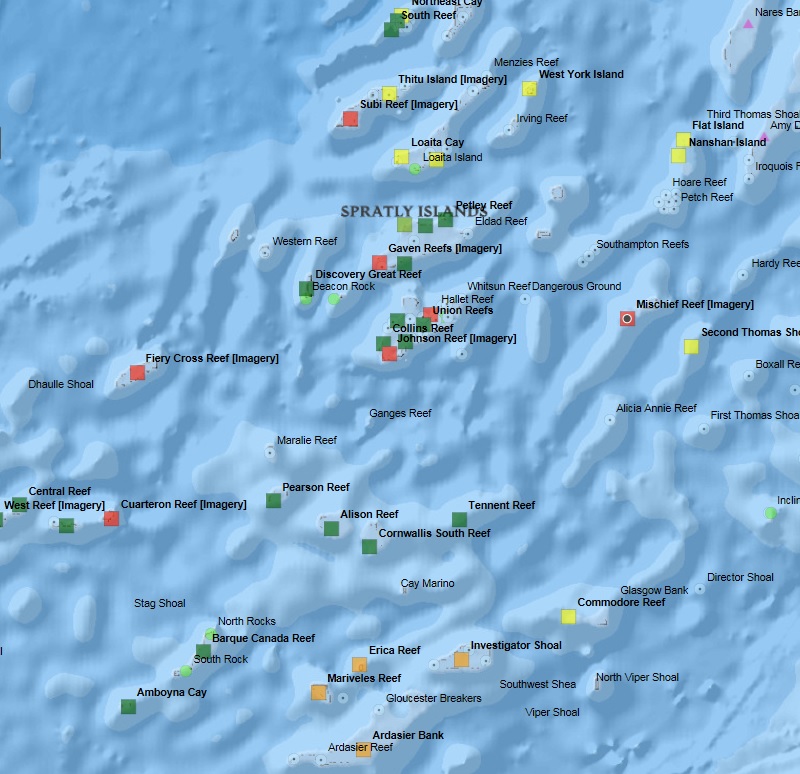

The PCA has agreed to address at least seven issues, mostly concerning the entitlements to specific features in the South China Sea—Mischief Reef, Second Thomas Shoal, Subi Reef, Gaven Reef, Hughes Reef (occupied by China and sometimes also mistaken for McKennan Reef), Johnson South Reef, Cuarteron Reef, and Fiery Cross Reef—as well as certain Chinese activities in the Philippine exclusive economic zone (EEZ). The PCA will follow the text of UNCLOS and prevailing international jurisprudence and likely limit drastically the maritime entitlements generated by these features.

Occupied Features in the Spratly Islands. Visit the Interactive Map to explore.

Any insular feature that remains above water at high tide is subject to appropriation or territorial title, and therefore may generate maritime entitlements through the provisions in UNCLOS. Such entitlements may include a territorial sea and contiguous zone for rocks and an EEZ and continental shelf for islands. Submerged banks are completely underwater and do not generate any maritime zones. When banks lie near the surface, they may create navigational hazards called “shoals,” on which low-tide elevations (LTE) or rocks may reside. Mid-ocean LTEs are not entitled to a territorial sea, contiguous zone, or EEZ.

Implicit in China’s claims is the belief that the features it occupies generate an EEZ and continental shelf. Recall that China’s 2009 note verbale to the UN Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf that distributed the nine-dash line to the international community was a rejoinder against an extended continental shelf claim by Vietnam and Malaysia and an affirmation of China’s territorial claims to the Spratly Islands. However, the PCA is likely to determine that none of the land features at issue are entitled to an EEZ or continental shelf, and that some are not entitled even to a territorial sea. This ruling will severely undercut China’s legal and therefore strategic position because it will legally isolate and enclose in enclaves China’s occupied features within the Philippine EEZ. Even if other states recognize China’s weak claim to historic title over the actual territorial features, the PCA will deny China the bonanza of maritime entitlements that its ambiguous claims imply. The court likely will reach this decision to tamp down excessive claims from insular features to prevent UNCLOS from unraveling. At the same time, the PCA will be compelled to protect the sanctity of the Philippine EEZ within which some of the contested features lie, since the principal legal basis for creation of the zone during the 1970s was to ensure subsistence fishing rights for developing countries.

Given the PCA’s uncomplicated and objective application of the law to the facts at hand, we can forecast with high confidence that the court will determine that Scarborough Shoal, Johnson South Reef, Cuarteron Reef, and Fiery Cross Reef do not generate an EEZ. These features are rocks that cannot sustain human habitation and generate at most a territorial sea of twelve nautical miles (nm). Scarborough Reef comprises a chain of reefs and submerged and dry rock outcroppings that form a 30-mile perimeter of outcroppings surrounding an atoll. The reef is located west of Subic Bay within the Philippine EEZ. Although no construction has occurred at Scarborough Shoal, China has cordoned off the lagoon to Philippine fishing vessels. Johnson South Reef has been built into an artificial island that has an area of 109,000 square meters (m2) and contains helipads, and Cuarteron Reef has been built into a 231,000 m2 island, also with helipads. China has developed Fiery Cross Reef into a massive 2.7 million m2 island with a 3,000-meter airstrip and deepwater harbor. But because all these features are rocks in their natural state and contain no indicia of natural capability to sustain human habitation or organic economic life, the PCA likely will declare that they are not islands and thus incapable of generating an EEZ.

The PCA is also likely to determine that Mischief Reef, Subi Reef, Gaven Reef, Hughes Reef (including McKennan Reef), and Second Thomas Shoal are all LTEs, which are not afforded any maritime zones in UNCLOS. The PCA will ignore the strategic significance that some of these features have acquired in recent years. Mischief Reef, for example, is 129 nm from Palawan Island but 599 nm from Hainan Island. China has reconfigured the LTE into an enormous artificial island spanning nearly 5.6 million m2. Subi Reef has likewise been reshaped into an artificial island expanse of nearly 4 million m2, with helipads, piers, and a potential 3,000-meter airstrip positioned only 14 kilometers from the Philippine Thitu Island. Hughes Reef has been built into a 76,000 m2 artificial island, and Gaven Reef is now an artificially constructed area spanning 136,000 m2. The decrepit Philippine warship BRP Sierra Madre, with eight Philippine Marines on board, is grounded on Second Thomas Shoal, another LTE in the Philippine EEZ. China has made repeated attempts to disrupt supply and maintenance of the ship, apparently in an effort to dislodge the garrison and claim the reef. By resolving the status of Second Thomas Shoal and other features as LTEs, the PCA will effectively eliminate their attraction to China because these features will be incapable of acquisition as territory.

The BRP Sierra Madre at Second Thomas Shoal (© JAY DIRECTO / AFP/Getty Images)

The PCA may disappoint those seeking greater clarity on some issues, however. The arbitrators are likely to avoid certain compelling questions and issue a narrow (and unanimous) decision. For example, the decision is likely to avoid altogether a direct repudiation of the nine-dash line. Although we can expect a ruling that restates that all claims must be “in accordance with UNCLOS and international law,” this language will fall short of taking on the nine-dash line directly. First, exactly what the line demarcates or claims is unclear, which leaves the PCA without any firm legal approach to address it. Second, the nine-dash line will be rejected anyway by implication of the territorial seas associated with the certain features. Although all eyes are fixed on the nine-dash line, the arbitrators likely will stick to the issues (and aforementioned features) at hand, avoid angering China any more than necessary, and deliver a narrow but unanimous ruling.

It is also unlikely that the arbitrators will address potential entitlements of Itu Aba under Article 121 of UNCLOS. While Itu Aba was mentioned by the Philippines in oral argument, it is not specifically referenced in Manila’s grounds for relief. Importantly, Itu Aba also was not identified in the award of jurisdiction. Since Itu Aba is the largest feature in the Spratly islands, it might appear that if the PCA clarifies that the feature is a rock not entitled to an EEZ, then no other feature enjoys such entitlement. But every feature or piece of territory is distinctive, and the metric for whether a feature is a rock or an island is not necessarily (or even principally) based on size. There is very little jurisprudence on Article 121, and it seems unlikely the PCA can craft a legal test while also holding together a unanimous panel.

Nonetheless, even with a limited decision, the PCA ruling will directly confront China’s strategic gambit in the region. Although Beijing has pledged to ignore the outcome, the follow-on effects from the decision will be devastating. First, China will lose face and the government will have to stretch legal logic even further to explain its position internally and overseas. China has responded to the case with continued denial, but the state’s more astute scholars and policymakers already realize that government pronouncements on the South China Sea have convinced no one outside China. The sheepishness of Chinese scholars and officials at innumerable meetings and conferences over the past decade may begin to penetrate into media accessible to the citizens of China.

Second, China is experiencing an education in the power of international law and its importance in the contemporary era. The moral or legal authority that arises from international law is often denigrated, and China lacks a tradition of the rule of law in which the law binds the strong as well as the weak. The decision will not make China walk back its claims or undo its island building, but it will challenge the country’s notion that the law is the instrument of the strong to control the weak. Ineffective as they are, international law and the moral authority of a liberal world order pose a central obstacle to Chinese ambitions.

Third, the case will embolden those who are on the fence on opposing China’s strategy in the South China Sea. States such as Cambodia, Indonesia, and Brunei that have been reticent to stand against China will have greater reason to do so. Domestic opposition to resisting China in Vietnam, Malaysia, and Indonesia will be weakened because the case will shift in these countries’ favor the cost-benefit calculus of standing up to China through arbitration.

Fourth, this legal and political dynamic makes it more likely that other states will initiate legal cases against China concerning the maritime entitlements under UNCLOS, and the effects will reverberate beyond the South China Sea. Both Vietnam and Japan are considering arbitration of their maritime disputes with China, and there will be little reason not to do so if the Philippines is successful, which is virtually assured. A ruling that denies an EEZ to any feature and limits entitlements to a territorial sea will affect other claimants—in particular, Vietnam and Malaysia, which also occupy tiny features. But like the Philippines, both states already possess extensive EEZs in the South China Sea by virtue of their mainland and large island entitlements, such as the EEZ generated from Sarawak. China is the only state dependent on extravagant island claims to assert jurisdiction over areas of the South China Sea. China now faces the prospect of a series of arbitrations in the South and East China Seas that will be a drawn-out process of cascading legal setback and embarrassments rather than a single, one-off case. The only way for the country to avoid compulsory dispute resolution for these types of cases is to withdraw from UNCLOS. Pandora’s box has been opened, and China will enter unsteady ground where adherence to the rule of law and good faith legal expertise by a vastly weaker state actually trumps a great power.

James Kraska is Howard S. Levie Professor of International Law in the Stockton Center for the Study of International Law at the U.S. Naval War College.

Download a pdf version of this analysis piece here.

Banner image source: © SAM YEH / AFP/Getty Images. [Editor’s note: Excavators at work on Itu Aba, an island controlled by Taiwan and claimed by multiple countries. It is the largest maritime feature in the Spratly Islands and the most likely to qualify as an island under UNCLOS.]