Inter-Korean Relations and Maritime Confidence-Building

Darcie Draudt (StratWays Group; Johns Hopkins University) explains why the porous maritime border on both sides of the Korean Peninsula has been a flashpoint for low-level provocations and maintains that leadership in Pyongyang, Seoul, and Washington will be necessary in order to overcome the impasse of the Korean Peninsula’s strategic environment.

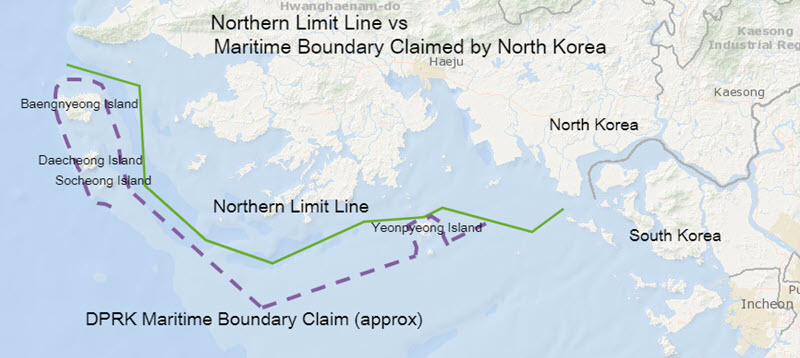

Since the Korean Armistice Agreement (KAA) was signed in 1953, the disputed maritime border has been a source of tension between the two Koreas as well as for their partners and allies in the region. Following the mutual agreement of the land border at the 38th parallel in the KAA, the UN Command stationed in the Republic of Korea (ROK, or South Korea) unilaterally drew a maritime boundary called the Northern Limit Line (NLL) as an extension of the land border. The two sides of the conflict had been unable to agree to a maritime border, and the UN commander at the time established the line to prevent inter-Korean clashes. To this day, both the UN Command and the United States continue to see the NLL as critical to fulfilling that function. South Korea has referred to the line as the maritime mechanism for maintaining the 1953 armistice as well as for practical security.[1] ROK strategists have also cited the political and strategic implications of including the disputed five Northwest Islands.[2]

By contrast, the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK, or North Korea) has never accepted the NLL. Since the 1970s, the North has more vocally contested the legality and legitimacy of the NLL. It declared its own demarcation line in 1999, which, as one North Korean researcher explained, was based on the KAA and the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea.[3] This line falls farther south of the NLL and gives the DPRK more control of the littoral West Sea (also known as the Yellow Sea) but leaves the Northwest Islands under South Korean control—practically speaking it carves out an awkward jagged maritime zone.

View of the Northern Limit Line (green) and the maritime boundary claimed by North Korea (purple) from the Maritime Awareness Project’s interactive map.

The United States, North Korea, and South Korea all view their side’s declared maritime boundaries as extensions of the Military Demarcation Line (MDL). As one ROK Army colonel wrote, the NLL has been a “practical sea demarcation line” since the KAA did not yield agreement on the maritime boundary, which in fact still remains in dispute to this day.[4] The United States and UN Command believe that the NLL has reduced the likelihood of a military clash between the two Korean military forces, even more so than at the time of the KAA signing. The UN Navy dominated the seas around the peninsula when the line was framed as a restraint on possible South Korean provocation or even irredentism. For its part, South Korea has been able to use the border to more effectively monitor Korean People’s Army (KPA) activity, hold off North Korean special forces that may come through the maritime border, and deter provocations.

Despite the utility of the NLL, the porous maritime border on both sides of the Korean Peninsula—at least relative to the highly militarized MDL—has been a flashpoint for low-level provocations. In addition to disputing the legality of the line, the North feels that its security is threatened because the NLL provides a strategic advantage to U.S.-ROK combined forces. South Korean strategists view it as important in the event of any contingency, as the Northwest Islands close to North Korean soil have been framed as a staging point for South Korean forces.[5]

Historically, North Korean provocations across the maritime border have increased the chances of escalation at sea. ROK military vessels regularly report North Korean civilian and military ships crossing into declared South Korean territory, and many are cautioned away with warning calls. However, depending on timing and the overall timbre of inter-Korean relations, seemingly low-level provocations can turn into national-level strategic issues. Two land-sea incidents in 2010 provide prime examples of the importance of de-escalation and arms control in the inter-Korean maritime domain.

In the lead-up to these incidents, a naval clash—the Battle of Daecheong—between ROK Navy and DPRK patrol vessels in November 2009 resulted in heavy damage to the North Korean vessel and eight North Korean casualties. The North Koreans had entered waters that South Korea claims according to the NLL and fired on the South Korean ship in response to warning shots. The North Korean navy established a “peacetime firing zone” that extended along the MDL into the waters of the Yellow Sea and said that it could not guarantee the safety of a military or civilian vessel crossing into these waters.[6]

A few months later, in March 2010, the sinking of the ROK’s Cheonan corvette in the Yellow Sea, just south of the NLL, led to a vitriolic series of accusations from both sides. An explosion near the ship caused it to break in half and sink, killing 46 South Korean personnel and injuring 56. Tensions were further exacerbated later that year in the area around South Korea’s Yeonpyeong Island. Joint U.S.-ROK forces conducted a scheduled large-scale joint exercise around the island, which butts up against the disputed maritime border. North Korea claimed that it would not tolerate any firing into what it viewed as its territorial waters.[7] Explaining that the maneuvers were a regular exercise and not an attack on the North, the allied forces fired 3,657 shells into contested waters near the NLL.[8] In response, North Korea fired artillery shells onto Yeonpyeong Island, which hosts South Korean military and civilian populations. The incident killed four South Koreans, including two civilians. Years later, former U.S. secretary of defense Robert Gates wrote that after the Yeonpyeong Island shelling, then president Lee Myung-bak was ready to retaliate in a manner that was “disproportionately aggressive, involving both aircraft and artillery,” but was persuaded by U.S. leaders to hold back.[9]

Official steps toward the most recent thaw in relations began with the inter-Korean summit between Moon Jae-in and Kim Jong-un in April 2018. This was the third meeting between Korean leaders. The others happened under the progressive administrations of Kim Dae-jung in 2000 and Roh Moo-hyun in 2007, both with the late North Korean leader Kim Jong-il. Steps toward demilitarization following those two meetings deteriorated due to a variety of factors. The North Korean leadership changed hands to Kim Jong-un in 2011 and continued its missile and nuclear weapons development and testing, while two successive conservative South Korean administrations took hard-line approaches toward the North.

In April 2018, as part of the Panmunjom Declaration coming out of the third inter-Korean summit, the two sides committed to “defuse the acute military tensions and to substantially remove the danger of a war on the Korean peninsula.” They agreed, among other commitments, to devise “a practical scheme to turn the area of the Northern Limit Line in the West Sea into a maritime peace zone to prevent accidental military clashes and ensure safe fishing activities.”

In September 2018, the DPRK and ROK defense ministers signed what is now known as the Comprehensive Military Agreement, or CMA (officially the Agreement on the Implementation of the Historic Panmunjom Declaration in the Military Domain). The CMA supplements the Pyongyang Joint Declaration signed between Kim Jong-un and Moon Jae-in in April 2018. The defense ministers set a goal to bolster the military element of the April agreement and to oversee halting “hostile acts” over land, sea, and air through a joint military committee. Measures to implement the agreement include setting up a 10-kilometer (km) buffer zone along the MDL (wider than the 4-km DMZ that runs along the MDL) in which artillery drills and field maneuvers will cease. In both the West Sea and the East Sea, the agreement calls for an 80-km wide “maritime hostile activities cessation area” to halt live-fire and maritime maneuver exercises.

Additional steps in the September 2018 CMA include inter-Korean joint patrol measures to ensure safe fishing activities for both South and North Korean fishermen and to prevent illegal fishing in the area. An annex to the agreement on establishing a maritime peace zone outlines specific rules and activities, including restricting entry to unarmed vessels; limiting entry hours to daylight times (7:00 a.m. to 6:00 p.m. from April through September and 8:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. from October through March); limiting vessels to their respective side of the agreed-on boundary line; prohibiting words or actions that may provoke the other side, including “psychological warfare” (unspecified); requiring both sides to fly a Korean Peninsula flag for the purpose of identification within the peace zone; and referring hostile or accidental clashes to inter-Korean working-level military consultations.

The movement to establish a peace zone has been augmented by an ROK proposal from the Ministry of Oceans and Fisheries, under consultation with the Ministry of Defense and Ministry of Unification, to create a joint fisheries zone along the NLL. This proposal would be contingent on relief of UN sanctions on North Korea. If an inter-Korean agreement on fisheries could be reached, fishermen from both the North and South could buy rights to enter the exclusive economic zone (EEZ).[10]

As of August 2019, both South and North Korea have abided by the spirit of the CMA. Both sides have rolled back artillery along the coastal areas on the West and East Seas, ceased psychological warfare broadcasts across the border, closed guard posts along the MDL, and abided by the stipulation of a no-fly zone. The ROK Coast Guard has also rescued several North Korean fishermen found adrift in South Korean waters. In mid-June 2019, two sets of fishermen were rescued after the ROK Coast Guard found their vessels adrift in the East Sea.[11] The six fishermen in the first group were all sent back to North Korea on humanitarian grounds. Of the second set of four, two claimed asylum in South Korea and two went back to North Korea. In July 2019, a Russian-flagged vessel that had two South Korean crewmen was detained in North Korean waters, and after ten days of detention the sailors were returned to the ROK.[12] These sorts of rescues and detentions are not unusual, but it is noteworthy that the decision to return the fishermen to their respective countries was both speedy and public.

Ultimately, the CMA’s goals in the inter-Korean maritime domain are more aspirational than practical. In a sense, the agreement and the annex establishing a peace zone are a reaffirmation of the KAA in an effort to reduce tension in the relationship. However, the CMA is not an arms control agreement, but a set of broad confidence-building measures. It will be difficult for North Korea to pursue the goals of the maritime annex because it disputes the NLL. The joint fisheries plan cuts into the competing EEZs on both coasts, and the practical considerations of civilian fishermen will make side-by-side operations difficult and potentially dangerous. Absent the dismantlement of North Korea’s nuclear program, U.S. sanctions relief, and (contingent on sanctions relief) ROK humanitarian assistance and economic investment, a true arms control agreement in the maritime domain is unlikely, if not impossible, at the strategic level.

Moon Jae-in has invested an immense amount of political capital on improving relations with Pyongyang. Although Kim Jong-un is feeling the crunch of a reportedly difficult economic outlook and is eager for normalized U.S.-DPRK relations and sanctions relief, he is unwilling to make any concessions on the North Korean nuclear weapons and missile programs without security guarantees that have been largely dismissed by U.S. strategists and policymakers. Donald Trump’s main goals ultimately come down to decreasing the burden of the United States’ military presence abroad (including with U.S. allies such as South Korea), finding new trade partners and areas for U.S. investment, and shoring up his administration’s reputation as a problem solver. All of these factors mean the stage has been set—after over two decades of inopportune triangle relations—for an unprecedented series of high-level inter-Korean and U.S.-DPRK meetings, including numerous leader-level summits. However, a workable maritime arms control process is contingent on a much broader set of demonstrated actions that require leadership in Pyongyang, Seoul, and Washington to overcome the impasse of the Korean Peninsula’s strategic environment.

Darcie Draudt is an Adviser at StratWays Group and a PhD Candidate in the Department of Political Science at Johns Hopkins University.

Download a pdf version of this analysis piece here.

ENDNOTES

[1] Moo Bong Ryoo, “The Korean Armistice and the Islands,” U.S. Army War College, Strategy Research Project, March 11, 2009.

[2] Terence Roehrig, “North Korea and the Northern Limit Line,” North Korean Review 5, no. 1 (2009): 8–22.

[3] Jong Kil Song, “Peace on the Korean Peninsula and the ‘Northern Limit Line,'” NK News, June 20, 2016, https://www.nknews.org/2016/06/peace-on-the-korean-peninsula-and-the-northern-limit-line.

[4] Ryoo, “The Korean Armistice and the Islands.”

[5] Ryoo, “The Korean Armistice and the Islands.”

[6] “KPA Navy Sets Up Firing Zone on MDL,” Korean Central News Agency (KCNA), December 21, 2009, available at https://kcnawatch.org/newstream/1451886777-84908937/kpa-navy-sets-up-firing-zone-on-mdl.

[7] “KPA Supreme Command Issues Communique,” KCNA, November 23, 2010, available at https://kcnawatch.org/newstream/1451888469-945036720/kpa-supreme-command-issues-communique.

[8] Ken E. Gause, “North Korea’s Provocation and Escalation Calculus: Dealing with the Kim Jong-un Regime,” CNA, August 2015, 14, https://www.cna.org/cna_files/pdf/COP-2015-U-011060.pdf.

[9] “GATES: America Prevented a ‘Very Dangerous Crisis’ in Korea in 2010,” Agence France-Presse, January 14, 2014, available at https://www.businessinsider.com/robert-gates-south-korea-airstrike-north-korea-2014-1.

[10] Kim Eun-jung, “Oceans Minister Proposes Joint Fishing Zone on Western Maritime Border,” Yonhap, August 16, 2018, https://en.yna.co.kr/view/AEN20180816007500320.

[11] “NK Fishermen Questioned for 2nd Day,” Yonhap, June 16, 2019, https://en.yna.co.kr/view/AEN20190616002800325.

[12] “Russian Boat Was Illegally Seized by North Korea: Russian Fishing Agency,” Reuters, July 24, 2019, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-northkorea-russia-ship-waters/russian-boat-was-illegally-seized-by-north-korea-russian-fishing-agency-idUSKCN1UJ1UO.

Image source: © AFP/Getty Images. South Korean Unification Minister Cho Myoung-gyon (3rd L) talks with his North Korean counterpart Ri Son-gwon (3rd R) during their meeting at the southern side of the border truce village of Panmunjom in the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) dividing the two Koreas on October 15, 2018.

South Korea in a Challenging Maritime Security Environment

South Korea in a Challenging Maritime Security Environment