Joint Development or Permanent Maritime Boundary

The Case of East Timor and Australia

Hong Thao Nguyen (Diplomatic Academy of Vietnam and the Vietnam National University) notes that both parties and the international legal community will have to reconsider the core issues underlying the disagreement in the Timor Sea case.

On January 9, 2017, Australia and Timor-Leste (also known as East Timor) entered a new chapter in their maritime disagreement with the release of a trilateral joint statement (PCA 2016-10) signed by the two relevant parties and the Conciliation Commission that was constituted pursuant to Annex V of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). In this new chapter, both the parties and the international legal community will have to reconsider the core issues underlying the disagreement, including those related to joint development, maritime boundary delimitation, the use of separate versus single lines, the validity of the agreements underlying the dispute, the status of newly independent states, state succession to international rights and obligations, the broader role of international law, and peaceful means for the settlement of disputes.

HISTORY

The maritime boundary issue in the Timor Sea dates to even before Timor-Leste first gained independence from Portugal. Indonesia, which annexed Timor-Leste in 1975 shortly after Portugal relinquished control, had claimed a continental shelf on the basis of the median line between the opposite coasts of Timor-Leste and Australia. The latter’s position was that the maritime boundary should follow the edge of the Timor Trough, 40 nautical miles (nm) from the southern shore of Timor and 250 nm from Australia. This position was based on the principle of the natural prolongation of the continental shelf, as endorsed by the International Court of Justice’s judgment in the North Sea Continental Shelf cases in 1969.

The development of the law of the sea in the years leading up to the 1982 UNCLOS provided for a new legal basis for delimitation in maritime areas where opposing shores are less than 400 nm apart. Articles 74 and 83 of UNCLOS require the application of the equitable principle or, pending final resolution of a dispute, the adoption of provisional arrangements of a practical nature that do not jeopardize or hamper the ability of parties to reach a final agreement. The Timor Gap Treaty (TGT) agreed to by Indonesia and Australia in 1989 divided the Timor Sea into three zones. In the south, Zone B was under the jurisdiction of Australia. In this zone, the proceeds of resource development were to be shared at a ratio of 90 to 10 in favor of Australia. In Zone C in the north, those ratios were reversed in favor of Indonesia. A zone of cooperation (Zone A) formed the center area between Zone B and Zone C and was administered by a joint authority. All jurisdiction, responsibilities, and revenues in Zone A were shared equally. The limits of the zone of cooperation were the respective claims of the two parties, while the Provisional Fisheries Surveillance and Enforcement Line ran along the median line between the Australian mainland and the Indonesian archipelagic baselines. Along with other joint development initiatives—such as those agreed to between Japan and South Korea (1974), Thailand and Malaysia (1979), and Malaysia and Vietnam (1992)—the TGT reaffirmed a strong tendency in practice to use joint development areas as an effective practical arrangement pending agreement on delimitation.

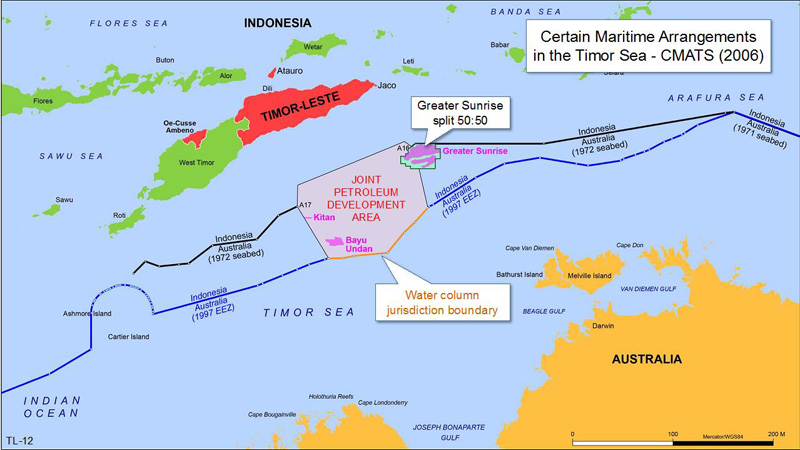

The joint development area in the Timor Sea and the seabed (black) and EEZ (blue) boundaries between Timor-Leste and Australia. This map was originally published in Timor-Leste’s opening statement at the September 2016 hearing of the Conciliation Commission.

The treaty, however, was rapidly extinguished when Timor-Leste seceded and refused to act as a successor to Indonesia’s international obligations in 1998. The Timor Sea Treaty signed between the newly independent Timor-Leste and Australia in 2002 created the Joint Petroleum Development Area (JPDA), similar to the previous Zone A but with a different sharing arrangement in which Timor-Leste received 90% of revenue and Australia only 10%. The new treaty maintained a separate boundary for the water column, which runs along the southern edge of the JPDA.

No sooner had this treaty been finalized than $40 billion worth of oil and gas was discovered in the Greater Sunrise field straddling the eastern border of the JPDA and between the water column and seabed boundaries, triggering renegotiations between the two parties over the unitization of the field. The majority of the Greater Sunrise find (80%) lies outside the JDPA. A new Sunrise International Unitization Agreement signed in Dili in 2003 allocated to Timor-Leste 18.1% of the revenue from the field. The subsequent Treaty on Certain Maritime Arrangements in the Timor Sea (CMATS), signed in Sydney in 2006, corrected this inequality by distributing revenue from the disputed areas of the Greater Sunrise field equally to each party. Australia considered the new sharing arrangement as favorable to Timor-Leste, which could now accrue a petroleum fund worth over $16 billion. In exchange, Article 4 of the treaty established a 50-year moratorium on negotiations on a permanent maritime boundary or referral to a court, tribunal, or other dispute-settlement mechanism. Timor-Leste continues to exercise jurisdiction over the water column within the JPDA.

CMATS did not produce a better outcome for Timor-Leste than the TGT because state practice and jurisprudence would likely consider an adjusted median line, taking all relevant factors into account, as providing the most equitable solution according to the spirit and provisions of UNCLOS. Based on such a line calculated from respective basepoints, Greater Sunrise would lie entirely within Timor-Leste’s exclusive economic zone (EEZ). State practice in implementing UNCLOS prefers a single line for continental shelves and the water columns of EEZs, even if the two maritime zone regimes have a different legal status. In 2012, revelations that Australia conducted espionage on Timorese negotiators triggered a push in Timor-Leste for arbitration as well as simultaneous pursuit of compulsory conciliation toward final settlement of the dispute under UNCLOS (leading to cases 2013-16, 2015-42, and 2016-10, as registered by the Permanent Court of Arbitration).

COMPULSORY CONCILIATION

The conciliation procedure invoked by Timor-Leste for the settlement of disputes was introduced in UNCLOS under Article 284 and Annex V of the treaty. Under Annex V, the conciliators are to “hear the parties, examine their claims and objections, and make proposals to the parties with a view to reaching an amicable settlement,” as well as to prepare a report after a year to record why a settlement could or could not be reached. Timor-Leste’s request for compulsory conciliation of its dispute with Australia marked the first employment of this mechanism. Australia objected to the competence of the commission by invoking Article 4 of CMATS and Articles 281 and 298 of UNCLOS. Article 281 privileges previous bilaterally agreed-on dispute-resolution mechanisms over those contained in UNCLOS, while Article 298 allows states parties to opt out of certain resolution mechanisms. According to Australia’s view, unless and until a decision is reached on the Timor Sea Treaty arbitration to nullify CMATS, the conciliation proceeding must be dismissed because CMATS remains “presumptively valid and must be treated as such.” In that parallel arbitration, Timor-Leste has claimed that Australia’s bugging of its prime minister’s office implied a failure to negotiate CMATS in good faith, rendering the treaty invalid.

Australian Prime Minister John Howard and Timor-Leste Prime Minister Mari Alkatiri watch as their respective foreign ministers, Jose Ramos-Horta and Alexander Downer, sign the CMATS in Sydney, January 12, 2006. (Greg Wood/AFP/Getty Images)

According to Article 13 of Annex V of UNCLOS, the commission decides its own competencies. Timor-Leste’s notification of its request for conciliation argues for the commission’s competence to interpret and apply Articles 74 and 83 of UNCLOS, covering not only the negotiation of permanent maritime boundaries but also transitional arrangements. Further, the request argues that the matters raised by Timor-Leste during hearings are not beyond the scope of its notification and are not barred by Australia’s Article 298 exemption from binding dispute settlement. The Conciliation Commission’s decision of September 19, 2016, rejected the Australian arguments and agreed with Timor-Leste, finding that while the validity of CMATS will be decided by the separate arbitration proceeding, the outcome of that process has no effect on the Conciliation Commission’s competence. The commission decided to initiate the twelve-month compulsory conciliation process on the same day.

The efforts of the commission and goodwill from the two parties can jointly produce an integrated package of measures and conducive conditions for a transitional and final solution in the Timor Sea. In an early signal of sufficient goodwill, the two governments have agreed to terminate the validity of CMATS while keeping the Timor Sea Treaty in its original form. In other words, Timor-Leste regains its right to conduct talks with Australia on a permanent maritime boundary in exchange for temporarily “losing” 50% of the revenue generated from the Greater Sunrise field outside the JPDA.

JOINT DEVELOPMENT AND MARITIME BOUNDARIES

The Timor Sea case produces several observations. First, international law is an important tool for the creation of peace, stability, and equitable outcomes in international relations. Small and developing countries have tended to be most eager to use the new dispute-settlement procedures provided by UNCLOS to safeguard their interests against larger partners. This is demonstrated not only in the case of the Annex V Conciliation Commission invoked by Timor-Leste in 2016 but also by the Annex VII arbitration requested by the Philippines in its case against China. Compulsory conciliation proceedings can be an option for claimants in the South China Sea dispute to overcome deadlock.

Timor-Leste’s Foreign Affairs minister Jose Luis Gutierrez speaks with Australian lawyer Bernard Collaery during proceedings before the International Court of Justice (ICJ) in The Hague, on January 20, 2014. The ICJ case stemmed from Timor-Leste’s accusations regarding Australian spying during the negotiation of CMATS. (Nicolas Delauney/AFP/Getty Images)

Second, the main cause of the dispute in the Timor Sea lies in the two parties’ different standards of equity, with Timor-Leste favoring the adjusted equidistance/median line and Australia the natural prolongation of the continental shelf. The trilateral agreement presents an active shift in the Australian position. Canberra now has an opportunity to avoid controversy and inconsistency in its attitude toward maritime law, when previously it supported the arbitral proceeding for the South China Sea while rejecting the competence of the Conciliation Commission for the Timor Sea. Negotiation of a permanent maritime boundary in the Timor Sea is achievable and would constitute a positive outcome if both parties demonstrate goodwill and a determination to settle the dispute. The boundary dispute between Japan and South Korea in the East China Sea—in which Japan favors delimitation on the basis of a median line, while South Korea argues for natural prolongation of the continental shelf—was put aside in a 1974 joint development agreement. The dispute between China and Japan, which has been managed in part through a 2008 agreement, sees Japan appearing to adopt the Timorese position and China Australia’s position.

Third, a permanent maritime boundary should consider the possibility of single or separate lines for continental shelves and EEZs. There is also the potential for talks with Indonesia to fix the tripoints between the concerned parties. Pending a final solution, the JPDA continues to have validity.

Fourth, joint development is a practical option for deadlocked jurisdictional disputes that provides access to the natural resources in the disputed area for economic purposes. The success of a joint development agreement depends on several factors, including political will, legal basis, economic factors, and the management model. The Timor Sea case demonstrates again that joint development is not a binding option to resolve maritime disagreements. The implementation of a joint development agreement does not release parties from the obligation to conduct negotiations on a permanent maritime boundary. The Timor Sea case has proved that a joint development plan can contain the seeds of its own potential failure. The Japan–South Korea joint development zone and the Japan-China area in the East China Sea, much like the JDPA in the Timor Sea, use a line based on the natural prolongation principle to define the limits of their zones, which can be inequitable in defining the zone of joint development and sharing ratios. Similarly, joint development between the multiple parties to the South China Sea dispute has not been successful because of the excessive claims represented by the nine-dash line and state actions taken to protest those claims. In some cases, the joint development model has adverse effects when it encourages claimants to maximize their unilateral claims for the purpose of expanding the geographic scope of a joint development zone (so as to increase revenue from exploitation activities in the area). This arrangement can only facilitate cooperation and the negotiation of a permanent maritime boundary if concerned parties display goodwill and realize a joint development area based on clear definitions of reasonable claims to maritime jurisdiction in conformity with UNCLOS.

Hong Thao Nguyen is a Professor of International Law at the Diplomatic Academy of Vietnam and the Vietnam National University. He has over 40 years of experience in diplomacy, high-level negotiations, and legal study and practice.

Editor’s Note: On January 24, 2017, Timor-Leste announced that it would drop its case at the International Court of Justice alleging Australian spying during the negotiation of CMATS. The move was framed as a goodwill gesture aimed at facilitating the progress of conciliation talks.

Download a pdf version of this analysis piece here.

Banner Image: © Valentino Dariel Sousa/AFP/Getty Images. East Timorese protesters hold a rally over a maritime boundary between East Timor and Australia, in Dili on March 22, 2016.