Lessons for an Unserious Superpower: Scoop Jackson on National Security and Human Rights in U.S. Foreign Policy (Part 1)

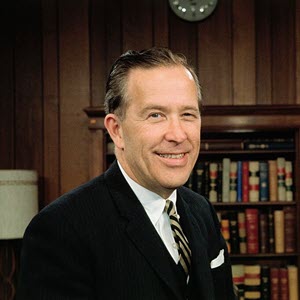

In this third essay in a series on the legacy of Senator Henry M. “Scoop” Jackson, Nicholas Eberstadt lays out the basic tenets of Senator Jackson’s worldview and considers how he might view the global threats and opportunities facing the United States today. This is the first installment of a two-part essay by Dr. Eberstadt.

Introduction

Forty years ago, when Senator Henry M. “Scoop” Jackson passed away, the global arena was vastly different from today. Americans raised in the post-Soviet era may have difficulty recognizing, much less fully comprehending, the enormity of those differences. Back in 1983—and in the decades preceding—the world was a very dangerous place, and serious Americans recognized as much. A Cold War was raging. The globe was largely divided into mutually hostile ideological blocs, led respectively by the United States and the Soviet Union, with very little direct contact, trade, or communication.

The Soviet Union was a formidable adversary, commanding what was widely believed to be the world’s second-largest economy as well as the largest arsenal of nuclear weapons.[1] The prospect of direct superpower conflict was never far off. On September 1, 1983, for example—the very day Scoop passed away—a Soviet jet fighter shot down a South Korean passenger plane that had inadvertently crossed into Soviet airspace, killing its 269 civilians, including a U.S. congressman, precipitating one of many Cold War–era crises that could potentially have spun out of control. Back then nuclear war was not “thinking the unthinkable.” Rather, it was the everyday background noise in both international strategy and public diplomacy, and it was operationalized through such U.S. doctrines as “extended deterrence” to defend otherwise indefensible outposts of freedom such as West Berlin.

Today, however, that great geopolitical saga is in the rearview mirror for most Americans: forgotten altogether, or else treated as quaint and ancient history. When discussed at all, it sometimes elicits irony and eye rolls. But as this great forgetting may in itself suggest, Americans are both less interested in, and seemingly less capable of, strategic thinking today, a generation after the collapse of the Soviet empire and the end of the Cold War, than they were back in Senator Jackson’s day.

That slackening of disposition and thought is not an inexplicable mystery. There are obvious reasons for it. Quite simply, neither the American public nor their elected representatives have needed the geopolitical acumen of their predecessors for quite some time. Our newfound diffidence about national security and international strategy relates directly to the victory of the U.S. alliance in the Cold War. That event was of such monumental significance as to result in a historically unprecedented preponderance of global power—economic, financial, scientific, and military—in the hands of the United States.

But our latest American holiday from history—we have taken such vacations before, remember—may be running its course. The extraordinary, utterly unprecedented surfeit of U.S. power is attenuating. As the U.S. “edge” reverts to more historically familiar proportions, Americans may no longer have the luxury of expensive indulgences and self-delusions in domestic and foreign policy. And so Americans will have to relearn much of what they have unlearned about geopolitics and national security since the Berlin Wall came down.

Jacksonianism of the Scoop Jackson Variety

As we try to regain our strategic bearings at a time when our national security strategy promises once again to have more immediate impact on American life, we could do much worse than to reacquaint ourselves with the basic precepts of “Jacksonianism” of the Scoop Jackson variety. Given that Scoop and his ilk exhibited a now-vanished political tendency—Congress has not had any “Scoop Jackson Democrats” for years—it is necessary to explain what he stood for in foreign policy.

Scoop Jackson’s politics did not wholly fit into intellectual categories familiar today. A member of the transition team after Ronald Reagan’s landslide 1980 electoral victory, staunch Democrat Jackson reportedly was offered the position of defense secretary but declined. While he found much to like in Reagan’s foreign policies, he deeply disagreed with “Reaganomics” domestically.

Jackson’s outlook aligned in some ways with the “neoconservative” intellectual and political movement of the 1970s and 1980s. One admirer even describes Scoop as “the avatar of neoconservatism.”[2] That compliment, alas, will mainly confuse nowadays. “Neocon” has become a term of opprobrium, associated with the unpopular U.S. intervention in Iraq two decades after Scoop’s death rather than with neoconservatism’s Cold War antecedents, whose precepts garnered wide public support. Even during the Cold War, neoconservatism was no monolith. In the late Soviet era, the movement bubbled with debate between those who endorsed Jackson’s foreign policy more or less in toto and those who objected to important parts of it.

So what then was the foreign policy of a “Scoop Jackson Democrat”? As a postwar Cold Warrior and liberal Democrat (a term with a very different connotation back then), Scoop held a worldview comprising three basic tenets.

First, he knew that the world was a dangerous place—full of adversaries and enemies, not just “competitors.” U.S. policy had to work ceaselessly to limit their power and their ability to impinge upon our own prosperity, security, and freedom.

Second, as an internationalist, Jackson was convinced that American prosperity, security, and freedom were best protected through alliances with like-minded states. Under the dictates of exigency, alliances with overseas friends who were rather less than perfect were also needed at times.

There was a third signature element of Scoop’s worldview, and this concerned human rights. Jackson’s deep love for and commitment to the U.S. polity—with its constitutional order, limited governance, rule of law, enshrinement of individual rights, and embrace of the “open society” (not his formulation, but one he would readily endorse)—led him to regard the promotion of human rights abroad as inseparable from the project of defending freedom at home. He understood very well that the international threats to the United States in the postwar era derived not just from the age-old pull of power politics, but from a very modern conflict of values and even ideologies as well. The American creed, and the postwar international order shaped and informed by that creed, was not only anathema to totalitarians and autocrats overseas—it was deeply threatening to their own projects.

To Jackson, the Cold War struggle could not be properly understood—much less won—without championing our own basic political ideals abroad. Thus, from the early years of his Senate tenure in the 1950s, he was already castigating the Soviet Union for its egregious treatment of its subjects and its systematic violation of both religious freedom and freedom of international movement for ideas and people. During the détente era in the 1970s, his Jackson-Vanik legislation conditioned improved U.S. economic relations with the Soviet Union on freedom of emigration from, and other basic human rights in, the country. To Jackson, defense of human rights was not just a moral imperative for U.S. leadership. It was a strategic advantage, thanks to our “American exceptionalism.”

In his day, Jackson had to contend with two powerful sources of opposition to the vision of human rights as a “force multiplier” for U.S. national security policy—perspectives which remain alive and well in U.S. foreign policy circles today. The first came from soi-disant “realists,” who held that ephemeral moralistic aspirations such as human rights had no real place in the agenda for defending and promoting the national interest. To these realists, preoccupation with human rights would be a distraction at best, and an invitation to dangerous blundering at worst.

Intellectually, the most important exponent of such “realist” thinking in Jackson’s day was former Harvard professor Henry Kissinger, a key architect of the détente of the 1970s under both Presidents Richard Nixon and Gerald Ford. Brilliant on paper, charming and persuasive in person, Kissinger preferred to “manage” the “competition” with the Kremlin, seeking a more favorable “equilibrium” for the United States than might otherwise obtain.

To Jackson’s way of thinking, however, a strategy that sought U.S.-Soviet “stability” without placing human rights squarely in the calculus made the United States all but complicit in the Soviet state’s suppression of its own subjects as well as those in “captive nations.” His point was inadvertently but vividly affirmed by Secretary Kissinger and President Ford themselves in the Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn affair of 1975. For fear of displeasing the Kremlin, the famous émigré was denied an audience at the White House, despite pleas from Jackson himself and many others.

Evidently, self-styled “realists” could botch great-power politics and sacrifice moral principle at one and the same time. But, fortunately, at the end of the day President Reagan had no compunction about terming the Soviet Union an “evil empire” or about charting a course for victory over Soviet Communism rather than mere “management of the competition.” Thus, with the end of the Cold War, the Scoop Jacksonian vision won out.

Jackson also faced a second, very different sort of intellectual challenge from a collection of voices in the 1970s that ostensibly favored human rights but were less certain about the propriety of maintaining relations with problematic U.S. allies. Some of these voices even seemed to harbor ambivalence about the propriety of U.S. power itself. This “New Left” point of view was associated with the radical and increasingly influential McGovernite wing of the Democratic Party, and eventually came to be associated with President Jimmy Carter himself, even though he was no man of the Left.

Jackson and his allies had neither patience for nor sympathy with such misguided, and ultimately self-defeating, international posturing under the banner of “human rights.” They recognized that the greatest threat to human rights around the globe was Communist power, and that while some clearly imperfect regimes with which Washington was allied were “reform-able,” Marxist-Leninist rights violators most decidedly were not.[3] For Jackson, pursuit of human rights required discernment—a principled weighing of competing concerns in a complex and dangerous world. Thus, he could favor rapprochement with Communist China, despite Beijing’s own grave rights violations at home, so as to harry Soviet power and check its advance, without entertaining or promoting any illusions about the Chinese regime itself. Morality played a central role in Scoop’s view of U.S. foreign policy. Carter-style moralism, by contrast, he eschewed—and with good reason, since it led not only to confusion in U.S. foreign policy but to setbacks overseas for the causes of freedom and human rights.

Although the Cold War is long over, the debate about the role of human rights in U.S. foreign policy most assuredly is not. Echoes of Kissinger’s “realism” and Carter’s New Left “moralism” reverberate in foreign policy circles today. Both perspectives still have influential proponents. There is still a strong case for Scoop Jackson’s counsel on this matter too, notwithstanding the momentous geopolitical changes of the past four decades.

A Scoop Jacksonian View of the Threats Facing the United States Today

How would Scoop Jackson view the global threats and opportunities facing the United States today? Of course, we cannot answer that question with complete certainty, but the foundations and principles of Senator Jackson’s worldview offer strong hints. They allow us to theorize about what a fusion of national security and human rights concerns in the Scoop Jackson tradition might look like for contemporary America. They would be put in practice in a markedly different world from the one Jackson knew, though—so we would do well to begin by describing the changed geopolitical terrain.

To begin, the world today is dramatically richer and more economically integrated than in 1983. Despite much faster population growth in poor regions, global per capita output has roughly doubled over the past 40 years, and per capita trade has more than tripled, both in real terms.[4] Thanks to growth and globalization, global poverty is at an all-time low. By one World Bank reckoning, the fraction of humanity living in “absolute poverty” plummeted from 45% in 1983 to under 10% in 2019 (and is likely still lower today).[5] The collapse of the Soviet empire and the rise of the Chinese economy both contributed to these trends. Also reinforcing them was a revolution in communications, connecting peoples around the world as never before. In 2019, on the eve of the Covid-19 pandemic, nearly two billion airline passengers flew internationally—ten times as many as in 1983.[6] By 2023, over five billion people (nearly two-thirds of the world’s population) were estimated to have access to the internet,[7] while nearly seven billion people (85% of the world) had access to cell phones.[8] Those two technologies were only nascent in Scoop’s time.

For its part, the United States is now far wealthier. Real U.S. private net worth overall is nearly five times as high as in 1983—more than tripling on a per capita basis. The U.S. dollar is the world’s reserve currency. Wealth is power. U.S. military might is also unrivaled. U.S. universities are still the envy of the world—perhaps even more dominant than in Scoop’s day. And in a form of soft power we seldom consider, the English language is likewise even more dominant in international trade, finance, research, science, and culture than 40 years ago—a reign abetted by the aforementioned communications revolution, in which it is the de facto “lingua franca.”

Yet the U.S. position in the world today reflects an extraordinary juxtaposition of paradoxes. For while the United States is richer than ever before, while enjoying unparalleled unilateral power in the world arena, Washington also demonstrates a continuing fecklessness in foreign policy formulation and execution that earlier generations would not have dared—and would never have been able to afford.

American post–Cold War foreign policy displays a deep and enduring streak of unseriousness, a puzzling but unmistakable proclivity for consistently subpar political leadership both at home and abroad under administrations from both political parties. Any number of examples could be adduced from the international arena: Bill Clinton’s insouciance in the face of the mounting menace of the al Qaeda terror network; George W. Bush’s deep gaze into Vladimir Putin’s “soul”; Barack Obama’s assurance that the United States could “lead from behind”; Donald Trump’s deliberately rude and often antagonistic treatment of U.S. allies; Joe Biden’s willful, completely unnecessary fiasco in Afghanistan. Suffice it to say, the behavior and decision-making of an entire generation of American presidents have been of a quality we might simply describe as uncharacteristic of a superpower. Consider: could any state become a superpower with the sort of leadership Washington has exhibited over the past three decades?

Let us be clear: the United States has had a very good run since the Berlin Wall fell and the Soviet empire collapsed. No country has ever been as prosperous; no economy before has ever been so productive. U.S. power—both hard and soft—is prodigious. All this has been possible despite the aforementioned fecklessness in U.S. policy.

But unseriousness in international affairs is ultimately unsustainable, even for a nation as wealthy and powerful as the United States today. The world is a moving target—and ominous global developments, some of them long underway, promise to force Americans to devote serious, undivided attention to national security and the international balance of power once again.

A number of features of the menacing new developments in the international security landscape would not only catch a Scoop Jacksonian’s eye but sound alarm bells:

- Europe is once again in flames, with a seriously weakened but nonetheless ambitious and assertive Kremlin slogged down in the second year of its invasion of neighboring Ukraine.

- An irredentist Iran has already cultivated an extensive and sophisticated Middle East military/terrorist network, covering or even dominating Syria, Iraq, Lebanon, and Gaza, and is committed to developing both nuclear weapons and the ballistic missiles to deliver them against its designated enemies, chief among them “little Satan” (Israel) and “great Satan” (the United States).

- North Korea, a tiny country with the world’s fourth-largest standing army,[9] is now a declared nuclear weapons state, has tested long-range missiles that can reach the continental United States, and is perfecting shorter-range rockets that could be used for conducting nuclear war against neighboring South Korea, a state it is doctrinally dedicated to eradicating.

- More portentous than any other emerging threat is the rise of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and the totalitarian Chinese Communist Party (CCP) that commands it. With four decades of remarkably rapid transformation, the PRC has emerged as the world’s second-largest economy, the top trade partner for most countries around the world, and a global leader in scientific and technological innovation. Its conventional and strategic forces have also rapidly modernized and continue to grow in both scale and capabilities. The CCP is expressly hostile to the United States and U.S. interests, and increasingly confident in its expressions of this hostility. Taiwan is the most imminent but not the only potential flashpoint for direct Sino-U.S. confrontation. And unlike the Soviet Union in the Cold War era, the PRC is deeply integrated into the economies of the United States and all its allies, affording the CCP opportunities for domestic political leverage against its adversaries that the Soviet Union never enjoyed.

- Finally, these four avowedly hostile actors—Moscow, Pyongyang, Tehran, and Beijing—are increasingly operating in concert. In 2022, Russia and China released a joint “no limits” declaration of their new partnership, just weeks before Putin’s decision to invade Ukraine.[10] North Korean leadership has backed Russian occupation of Ukrainian territories at the United Nations and contracted to supply ammunition to the Russian Army, with Kim Jong-un publicly toasting Putin to wish for Russian victory in Ukraine.[11] Tehran is also supplying drones and possibly other military materiel to Russia for its war in Ukraine.[12] Iran relies on support from North Korea, China, and Russia not only diplomatically but also in its WMD development program. And in the wake of the October 7 pogrom in Israel by Hamas terrorists—Iranian proxy forces—the four states revealed something like a four-way diplomatic coordination in defense of the indefensible that may be just a foretaste of what lies ahead internationally.

How would a Scoop Jacksonian respond to the challenges that the United States faces today in the world arena? How should we marry national security and the promotion of human rights internationally in our current complex global environment? How ought we address the threats posed by today’s aggressive revisionist states, the post–Cold War governments—the PRC chief among them—that ally themselves in opposition to Pax Americana and regard themselves as being in ideological struggle against the United States and its allies?

We can be sure that Scoop Jackson himself would have had answers to today’s pressing international questions. Part 2 of this essay will suggest what a contemporary U.S. foreign policy informed by a Scoop Jacksonian sensibility might look like.

Read part 2 of this essay: Lessons for an Unserious Superpower: Scoop Jackson on National Security and Human Rights in U.S. Foreign Policy (Part 2)

Nicholas Eberstadt holds the Henry Wendt Chair in Political Economy at the American Enterprise Institute and is a member of the Board of Advisors at the National Bureau of Asian Research (NBR). He researches and writes extensively on demographics, economic development, and international security, inter alia publishing numerous studies on Korean affairs. His association with NBR began in the early 1990s.

Endnotes

[1] Hard as this may be to recall today, 40 years ago China was still a decidedly secondary global player, with scant economic, military, or technological capabilities, just starting to “open up” under Deng Xiaoping. In the year of Scoop Jackson’s death, China’s global export totals were comparable to Iran’s or Norway’s, and the Netherlands was exporting over three times as much as China. This is despite the fact that China was already the world’s most populous country. See “World Development Indicators DataBank,” World Bank, https://databank.worldbank.org/reports.aspx?source=world-development-indicators.

[2] Joshua Muravchik, “‘Scoop’ Jackson at One Hundred,” Commentary, July/August 2012, https://www.commentary.org/articles/joshua-muravchik/scoop-jackson-at-one-hundred.

[3] Jackson’s friend and ally Jeane Kirkpatrick made this point to withering effect about the Carter policy in her 1979 essay “Dictatorships and Double Standards,” available at https://www.commentary.org/articles/jeane-kirkpatrick/dictatorships-double-standards.

[4] “World Development Indicators DataBank,” World Bank.

[5] Nishant Yonzon et al., “Estimates of Global Poverty from WWII to the Fall of the Berlin Wall,” World Bank, November 23, 2022, https://blogs.worldbank.org/opendata/estimates-global-poverty-wwii-fall-berlin-wall.

[6] “World Air Passenger Traffic Evolution, 1980–2020,” International Energy Agency, December 3, 2020, https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics/charts/world-air-passenger-traffic-evolution-1980-2020.

[7] Rohit Shewale, “Internet User Statistics In 2023—(Global Demographics),” DemandSage, August 21, 2023, https://www.demandsage.com/internet-user-statistics/#:~:text=There%20are%205.3%20billion%20internet,has%20access%20to%20the%20internet.

[8] Josh Howarth, “How Many People Own Smartphones (2023–2028),” Exploding Topics, January 26, 2023, https://explodingtopics.com/blog/smartphone-stats.

[9] “Military Size by Country 2023,” World Populations Review, https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/military-size-by-country.

[10] Chao Deng et al., “Putin, Xi Aim Russia-China Partnership Against U.S.,” Wall Street Journal, February 4, 2022, https://www.wsj.com/articles/russias-vladimir-putin-meets-with-chinese-leader-xi-jinping-in-beijing-11643966743?mod=article_inline.

[11] Alona Mazurenko, “Kim Jong Un Toasts to Putin’s Health and Wishes Him Victory in War,” Ukrainska Pravda, September 13, 2023, https://www.pravda.com.ua/eng/news/2023/09/13/7419615.

[12] Aamer Madhani, “White House Says Iran Is Helping Russia Build a Drone Factory East of Moscow for the War in Ukraine,” Associated Press, June 9, 2023, https://apnews.com/article/russia-iran-drone-factory-ukraine-war-dfdfb4602fecb0fe65935cb24c82421a.