Perspectives on the South China Sea Dispute in 2018

Hong Thao Nguyen and Binh Ton-Nu Thanh (Diplomatic Academy of Vietnam) summarize the challenges and opportunities confronting claimants and interested parties in the South China Sea after a year of Chinese successes.

In 2017, China strengthened its position in the South China Sea dispute in at least five ways. First, it expanded its construction activities on Fiery Cross, Subi, and Mischief Reefs in the Spratly Islands and on North, Tree, and Triton Islands in the Paracel Islands. Since 2014, China has added a total of 290,000 square meters, or 72 acres, of new landmass. The expansion of artificial islands has reinforced its overall ability to control the South China Sea—for example, by allowing for the deployment of fighter jets in the region. For this reason, Xi Jinping praised this achievement as a “highlight of his first five years” at the 19th Communist Party Congress.

Second, China’s breakthroughs in scientific and technical achievements played an important role in increasing its influence in the South China Sea. The country’s first indigenous aircraft carrier is ready to enter the fleet, while a second may set sail as early as the end of 2018. Remote-sensing satellites to cover the region are also being prepared for sequential launch. The proposed construction of floating nuclear plants, the creation of a deepsea surveillance network to match those of maritime peers, and the launch of two new ultra-deepwater offshore exploration platforms, Bluewhale I and II, further illustrate China’s upgraded capacity to dominate the entire South China Sea in the face of competing claims. Most importantly, economic incentives to expand Chinese control over maritime areas inside the nine-dash line have been revitalized by the development of new technology for finding and exploiting flammable ice, although economically feasible exploitation may be years away.

Third, China has put great effort into launching a large propaganda operation to prevent implementation of the 2016 arbitration award in its dispute with the Philippines. The measures China has taken are various, including promulgating its “four no’s” policy (nonparticipation, nonrecognition of the arbitration panel’s jurisdiction, nonacceptance, and nonenforcement of the award), adopting new laws and regulations (such as a revision of the 1984 Maritime Traffic Safety Law to require prior notification for foreign vessels entering Chinese territorial seas), and reinforcing its claims through the Four Sha doctrine. The latter argues that (1) China has sovereignty over the Nanhai Zhudao (the South China Sea Islands), including the Zhongsha Islands (Macclesfield Bank), Dongsha (Pratas) Islands, Xisha (Paracel) Islands, and Nansha (Spratly) Islands, and (2) these islands are entitled to internal waters, territorial seas, contiguous zones, exclusive economic zones (EEZs), and continental shelves. Thus, China has positioned itself to replace the nine-dash-line claim rejected by the arbitration award with maritime claims emanating from land features that are more consistent with the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). However, China’s claim that tiny, even low-tide, features should be accorded maritime zones exceeding a 12 nautical mile (nm) territorial sea still runs counter to both UNCLOS and the arbitration award. While there are no signals that the tribunal’s decisions will be implemented by the parties to the case, China and the Philippines, in the short term the award has become an important landmark in international law.

Philippines President Rodrigo Duterte (L) shakes hands in Hanoi with Vietnamese Prime Minister Nguyen Xuan Phuc on Sep. 29, 2016. Philippines Presidential Communications Operations Office.

Fourth, China has improved its position in its relations with the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). Applying a policy of presenting an “iron fist in a velvet glove,” China granted economic aid and offered the blissful prospect of infrastructure development through the Belt and Road Initiative, while also applying pressure through threats of the use of force. As a result, ASEAN’s unity was undermined through its own principle of consensus. Chinese prime minister Li Keqiang and Cambodian prime minister Hun Sen issued a joint statement in 2017 calling for relevant parties to adopt a code of conduct (CoC) and to continue implementation of the Declaration of Conduct of Parties in the South China Sea (DoC). The Philippines even seemed to support China’s militarization of artificial islands in the South China Sea, due to a belief that the threat they pose “is not intended for [the Philippines]” but rather for China’s rival states, such as the United States. In addition, China has tried to use the CoC talks to keep extraregional countries out of the dispute, which would help China retain influence over ASEAN countries on this issue.

This is also where China gained its fifth achievement: the successful engagement of its coast guard, paramilitary, and other maritime law enforcement in the exercise of control and assertion of sovereignty over the South China Sea. The presence of Su-35 and J-20 fighter jets in the region can be regarded as Beijing’s “direct response to American provocations.”

THE UNITED STATES AND ASEAN RESPOND

China’s provocative activities in the South China Sea in 2017 contrast with the United States’ and ASEAN’s negligence. Due to its policy of “America first” and concerns about the nuclear crisis on the Korean Peninsula, the Trump administration did almost nothing except for performing five freedom of navigation operations (FONOPs) near China’s military bases. FONOPs are one of the tools used by the U.S. government to challenge excessive maritime claims. Yet in the South China Sea, FONOPs only have had the effect of demonstrating U.S. presence and are unlikely to prevent the construction of artificial islands or enhance the confidence of regional countries.

The USS Carl Vinson in the Arabian Gulf on Dec. 8, 2014. U.S. Navy/Alex King.

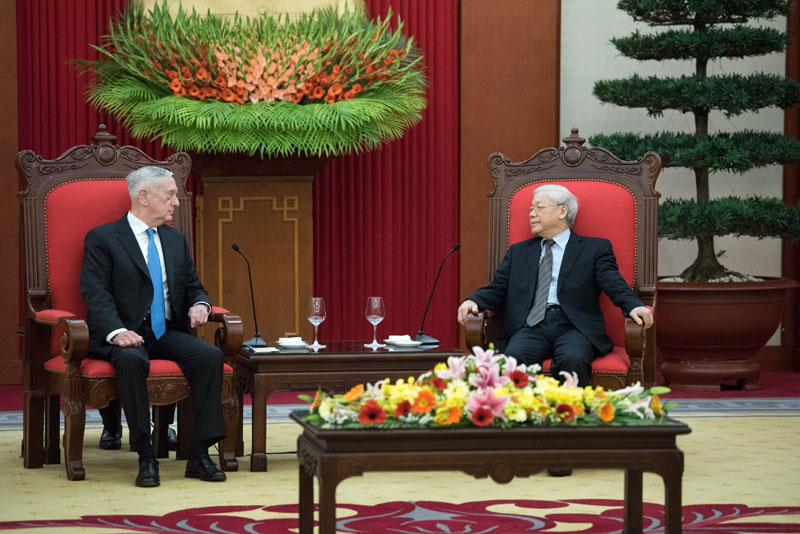

However, the situation may change in 2018. The new U.S. National Security Strategy, released in December 2017, identifies China as a competitor, while the new U.S. National Defense Strategy stresses the importance of cooperation on national defense with other countries. Secretary of Defense James Mattis paid two visits to the region, to Indonesia and Vietnam, in early 2018 to begin implementing this strategy and promoting the new “free and open Indo-Pacific” concept, which replaces the ineffective “rebalancing” strategy of the Obama administration. During his visit to Indonesia, Mattis supported Jakarta renaming part of the South China Sea around the North Natuna Islands as the North Natuna Sea, a symbol of Indonesia’s intention to counter China’s ambitious maritime claims. During Mattis’s trip to Vietnam, it was announced that the aircraft carrier the USS Carl Vinson would visit Da Nang in March 2018, the first time such a symbol of American power has visited the country since the Vietnam War. At around the same time, the USS Hopper missile destroyer was conducting a FONOP within 12 nm of Scarborough Shoal, which provoked strong criticism from China. So far, the U.S. maneuvers in the South China Sea are based on the rules of international law, including the customary right to freedom of navigation. To support the U.S. policy, Australia and the United Kingdom have indicated their intentions to conduct similar operations.

ASEAN, on the other hand, wishes to regain its central position in the region in 2018, with the second ASEAN-India Summit and statements that urge the adoption of a CoC. As ASEAN chair in 2018, Singapore will provide effective leadership, although it will face a range of potential challenges, with elections in Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, and Cambodia; the Rohingya crisis in Myanmar; and continuing tensions in the Philippines. Singapore has maintained an independent policy, despite incidents such as the impounding of Singaporean armored vehicles in Hong Kong, which caused some tension with China. The island state has always been supportive of freedom of navigation and adherence to international law—important contributors to its strong economy. Minister of Foreign Affairs Vivian Balakrishnan stated in December 2017 that the top shared interest of ASEAN members is the right to freedom of navigation and overflight, because all the states are dependent on trade and therefore on peace and stability. According to Balakrishnan, ASEAN countries want a rules-based international order, “not just because international law itself is something so powerful, but because international law provides avenues for the peaceful resolution of disputes.” The ASEAN Foreign Ministers’ Meeting in Singapore on February 5–6 issued a statement expressing concern over China’s land-reclamation activities in the South China Sea and urging negotiations on the CoC.

Philippines Secretary of Defense Delfin Lorenzana (L) poses with his Singaporean counterpart Ng Eng Hen at an ASEAN Defense Ministers meeting on Oct. 24, 2017, in Clark, Philippines. U.S. Department of Defense/Amber I. Smith.

OPTIONS FOR DISPUTE MANAGEMENT

Two measures for settling and managing the dispute in the South China Sea that will surely be discussed in 2018 are joint development and the long-delayed CoC. Joint development under Articles 74 and 83 of UNCLOS is a provisional measure applied only in maritime zones with overlapping claims and is not a tool for resolving sovereignty disputes. Joint development can produce economic benefits in cases of overlapping maritime entitlements absent sovereignty disputes, as exemplified by the 1992 Vietnam-Malaysia joint-development program in the Gulf of Thailand or the joint fishery zone shared by Vietnam and China in the Gulf of Tonkin. However, in the South China Sea, the mixture of maritime and sovereignty claims, together with the implications of the arbitration award in the dispute between China and the Philippines, creates difficulties for joint development due to the absence of common legal ground and interpretations. China uses joint-development proposals to convince countries to recognize its sovereignty claims and reject the arbitration ruling. Its proposal to “set aside disputes and pursue joint development” is conditioned on recognition that “sovereignty belongs to China” and all features in the Spratly Islands are entitled to EEZs and continental shelves.

By contrast, other claimants believe that their 200-nm EEZs and the continental shelves emanating from their mainland territories should be beyond dispute. Vietnam, in particular, will continue to consider the EEZ extending 200 nm from its mainland to be undisputed. This conclusion follows from its interpretation of the arbitration award. Joint activities must be carried out on the basis of Vietnam’s concept of “cooperation for mutual development,” which includes both joint development in areas of real dispute, such as outside the entrance of the Tonkin Gulf, and joint ventures carried out in maritime zones under national jurisdiction. The Philippines has recently suggested that any potential deals between Manila and Beijing on energy exploration in the South China Sea should be agreed on with Chinese firms rather than the government. The Philippines appears to be seeking joint ventures on the continental shelf under its jurisdiction in furtherance of the “principle of mutual interest,” instead of establishing a true joint-development program in disputed zones.

Da Nang harbor, Vietnam, May 9, 2012. Flickr/Creative Commons/Allan Watt.

Negotiations on a CoC between ASEAN and China will begin in March 2018 in Hanoi. The two sides have called for in-depth discussions on the content of the instrument in order to reach an effective and legally binding CoC that contributes to the promotion of peace and stability in the region. However, differences over the scope, rules of application, covered parties, and the degree to which the code will bind states have the potential to dilute the agreement. The CoC could become more like a forum, a channel of communication, than a strong measure in practice. Throughout the negotiations, states also need to fully implement the DoC and apply confidence-building measures.

VIETNAM’S STANCE

With China likely to intensify its civil and military presence in the South China in order to advance its claim that the region is a core interest, alongside Xinjiang, Tibet, and Taiwan, 2018 will not be a calm year. The semiofficial but hawkish Global Times reacted to the visit of the United States’ Carl Vinson aircraft carrier to Vietnam by insisting that the “two countries’ military cooperation should not cross the red line of violating China’s core interests.” While the Philippines has shifted its position closer to China’s, and other countries have voiced inconsistent policies, Vietnam holds to its “three no’s” defense policy (no military alliances, no foreign military bases on Vietnamese territory, and no reliance on any country to combat others). The adherence to international law is a real “core interest” and a “red line” for Vietnam and other countries. It enables them to protect their sovereignty, territorial integrity, and other legal interests to which they are entitled under UNCLOS, while maintaining friendly relations with all countries and creating a new legal order in the South China Sea. Vietnam will deepen its relationships with other countries based on mutual respect and common interests, respect for international law, and recognition of national sovereignty. In this context, conduct such as FONOPs and friendly port calls will be welcomed.

U.S. Secretary of Defense James N. Mattis meets with the General Secretary of the Communist Party of Vietnam Nguyen Phu Trong in Hanoi, Jan. 24, 2018. U.S. Department of Defense/Amber I. Smith.

In 2018, Vietnam and Singapore will both play important roles in pushing for a CoC under the ASEAN framework—Vietnam as an active member and Singapore as the chair. Vietnam’s deputy prime minister and minister of foreign affairs Pham Binh Minh, at the recent ASEAN Foreign Ministers’ Meeting in Singapore, called on member countries to stand up for ASEAN viewpoints on regional and international issues of mutual concern, including those regarding the South China Sea. Countries should support safety of aviation and navigation and reiterate their commitments to resolving disputes via peaceful means and in line with international law, including UNCLOS, he said. He also expressed Vietnam’s hope that ASEAN and China have more practical exchanges to reach an effective and binding CoC, making significant contributions to promoting peace and stability in the region.

Hong Thao Nguyen is an Associate Professor at the Diplomatic Academy of Vietnam.

Binh Ton-Nu Thanh is a Research Assistant at the Bien Dong Institute for Maritime Studies and a Member of the Galileo Society at the Diplomatic Academy of Vietnam.

Download a pdf version of this analysis piece here.

Banner Image: © U.S. Navy/Justin A. Schoenberger. U.S. Navy sailors aboard the USS San Diego at Cam Ranh International Port, Vietnam, on August 6, 2017.