Remembering Scoop

On September 1, 1983, Senator Henry M. “Scoop” Jackson passed away shortly after returning from a trip to China. This essay by Kenneth Pyle, founding president of NBR and Henry M. Jackson Professor Emeritus at the University of Washington, is the first in a series honoring Scoop’s legacy.

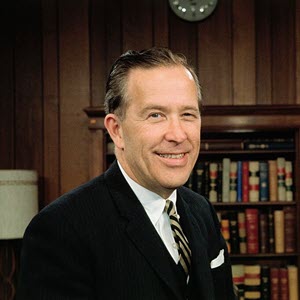

Forty years ago on September 1, 1983, one of our great statesmen and senators died at the relatively young age of 71. His achievements, principles, and personal character are worth remembering. I had the extraordinary privilege of knowing Henry “Scoop” Jackson. He asked me to accompany him on his trips to China when he was the guest of Deng Xiaoping and to keep record of their lengthy discussions, which centered on the Sino-Soviet split. In these and other activities I was able to be with him often in the last years of his life. The National Bureau of Asian Research (NBR) honors his memory as the one who inspired our founding. He believed in the future importance of Asia and in the need for an informed foreign policy for our relations with that region.

In this photograph taken in 1983, just three weeks before his death, Senator Jackson stands next to Deng Xiaoping in the front row. Professor Pyle is on the right standing next to Dorothy Fosdick, Scoop’s foreign policy adviser.

Senator Jackson served in Congress for a half century through the terms of nine presidents, from FDR to Reagan, and was twice himself a candidate for president. He came from a modest background in the working-class town of Everett, Washington, a child of Norwegian immigrants, loved by the overwhelming majority of people in the state. The first election in which I was able to vote for him, 1970, was one of the most divisive because of the Vietnam conflict. Senator Jackson won with 84% of the vote.

People were drawn to him by his personal character as well as his policies. With Scoop there was none of the bitterness and the poisonous partisanship that one finds in Washington today. Although a liberal Democrat, to get things done he was comfortable in working with others of different persuasions, on both sides of the aisle. On the first trip I took to China with Senator Jackson and his family in 1979, a young naval captain John McCain was assigned by the Congress to accompany us. Later, as a Republican candidate for president, McCain wrote:

-

The great Scoop Jackson of Washington was and remains for me a model of what an American statesman should be.…. Few members of Congress have ever accumulated the record of accomplishment and influence Jackson had.… Most of all, Scoop had faith in his country, faith in the rightness of her causes. He had faith that our founding ideals were universal, the principal strength of our foreign policy, and would in time overcome our enemy’s resistance. Until the day he died, he never wavered in his faith…. Although many in his party and mine would fault him for being too stubborn in a world that required subtlety and cunning, he was a hero for our time, the last half of a violent century, and absolutely indispensable for our success [in the Cold War]. Few presidents can claim to have served the Republic as ably, as faithfully as Scoop Jackson did…. He was, to me, and many others, an ideal whose example I revered.

In this photograph from 1979, Senator Jackson’s wife Helen and their children Anna Marie and Peter are in the front row. Professor Pyle is fifth from the left and John McCain is second from the right in the back row.

Scoop’s concern with the common welfare led to his achievements in environmental, energy, land use, and labor legislation. He was largely responsible for an array of remarkable legislation that served the needs of his region and the nation: the National Environmental Policy Act of 1970, which was the pioneer legislation in setting national policy on environmental protection. Then there was his leadership in achieving the legislation that set aside 60 million acres of land for parks and wilderness areas. In addition to pioneering environmental legislation, following the oil shocks of the 1970s he gave leadership as chair of the Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources to passage of the National Energy Act of 1978 and a raft of associated legislation that aimed at conserving natural gas, reducing dependence on foreign oil, increasing usage of renewable energy, and developing hydroelectric power.

Senator Jackson’s significance in American history will be defined by many things, but above all by his critical role in the Cold War. It was what preoccupied his attention at the height of his career. Scoop came to Congress just before Pearl Harbor, but it was at the end of the war that his foreign policy thinking crystallized. At the invitation of General Eisenhower, he visited Buchenwald in the spring of 1945, just eleven days after General Patton’s Third Army had liberated the death camp. There he saw firsthand the evidence of the horror of the Holocaust. His travels in the war-ravaged and demoralized Europe at that time, including a visit to his parents’ native Norway and the Norwegian fear of Soviet expansionism, shaped his thinking. When the Cold War broke out, he believed that only strong U.S. leadership and an internationalist foreign policy that galvanized the democracies would thwart Stalin’s expansionist designs.

Senator Jackson was at the center of three profoundly important turning points in the Cold War, each of which probed and exposed the vulnerabilities of the Soviet system. First, he was the leading critic of the arms control agreements that Nixon and Kissinger were trying to negotiate with the Soviet Union. He insisted that such agreements be based on parity and be aimed at reductions, something the Soviet leaders were loath to grant. Second, Senator Jackson was a leader in pressing for normalization of relations with China, which changed the balance of power in the East-West struggle. Third, through the Jackson-Vanik amendment to the Trade Act of 1974, he introduced the deeply troubling issue for Soviet leaders of how they were to treat their own people. Jackson-Vanik linked trade benefits, which the Soviet Union desperately needed, to an improvement of human rights, especially the right to emigration.

Henry Kissinger’s effort to reach a détente with the Soviet Union would have allowed its leaders to stabilize their relations with the West. Kissinger believed that given the nuclear stalemate it was not feasible to seek victory in the Cold War. The two superpowers should find ways to stabilize their relations through agreements and compromises. If it meant that peoples in the Communist world would be indefinitely denied the liberties that people in the West enjoyed, then that was the price that must be paid for global security. Given what we now know of the vulnerabilities of the Soviet system, the policy of détente seems no longer defensible. The Jackson-Vanik amendment brought to light the internal contradictions of the Soviet system and was a critical blow to the Soviet Union. Senator Jackson was anathema to Soviet leaders. The dissident Natan Sharansky recalled that when the KGB put him on trial for treason

-

there was one name mentioned not once, not dozens, but hundreds of times, the name of the man who was singled out as head of this plot, as my closest and most important comrade in crime. It was the name of a man whom I had never met or spoken to on the telephone, but who symbolized for me all those in the free world who had supported the struggle for Soviet Jewry, the very best that was in the West. It was the name of Senator Henry Jackson.

Many people called Scoop a Cold Warrior or a hawk, but that did not bother or deter him. He had many critics in his own party who viewed his attention to the domestic affairs of the Soviet Union as an obstruction to the pursuit of a peaceful world. Senator J. William Fulbright, a persistent critic of Senator Jackson for focusing on human rights violations in the Soviet Union, said that

-

learning to live together in peace is the most important issue for the Soviet Union and the United States, too important to be compromised by meddling—even idealistic meddling—in each other’s affairs…. It is simply not within the legitimate range of our foreign policy to instruct the Russians in how to treat their own people, any more than it is Mr. Brezhnev’s business to lecture us about race relations or such matters as the Indian protest at Wounded Knee.

Despite such criticism, Senator Jackson held to his strong views on arms limitation talks and human rights.

As Senator Patrick Moynihan said in his eulogy of Scoop, “He lived in the worst of times—the age of the totalitarian state. It fell to him to tell this to his own people and he did so knowing full-well that there was a cost for such truth telling. But he was a Viking also and knew the joy of battle.” I was in the White House Rose Garden several months after his death when President Reagan awarded him the Medal of Freedom posthumously and his widow Helen Jackson accepted it. The president concluded his remarks by describing Senator Jackson as “the greatest bipartisan of our time,” who deserved to be thought of as one of the all-time great senators along with Clay, Calhoun, Webster, LaFollette, and Taft.

The bedrock of Scoop’s character was his devotion to the highest principles of personal and professional conduct. When he died, I remember a stirring eulogy by the columnist George Will who wrote that “heroes make vivid the values by which we try to live. I say unabashedly, with many others: Henry Jackson was my hero…. Henry Jackson mastered the delicate balance of democracy, the art of being a servant to a vast public without being servile to any part of it. He was the finest public servant I have known.” Many people said and thought the same thing. David Broder, the Washington Post correspondent, wrote: “‘Scoop’ Jackson was a protector of the land and its people, an environmentalist (before we knew the word) and a battler for civil rights…. But he was also a strong defense advocate and an implacable anti-communist. Most of all, he was a thoroughly decent, upright public servant who trained a long string of others of similar bent.”

The policy positions Senator Jackson took had a consistency and clarity that leave little doubt about how he would view our struggle with the authoritarian regimes of Xi Jinping and Vladimir Putin. He would be a leader in rallying the democracies and advocating a strong American deterrence, holding hearings to gather views of specialists on foreign policy issues whose judgment he respected. “Judgment,” he said of people in government, “is the most valuable of all qualities—the ability to make good decisions in the face of uncertainty.… Study of history is the foundation of wisdom in decision making. Poor decisions,” he emphasized, “were so often traceable to the failure of people to comprehend the full significance of information crossing their desks, their indecisiveness, or their lack of wisdom.” He was passionate about the importance of understanding the histories and cultures of the countries that the United States had to deal with. Not only by reading but also by extensive travel, he educated himself. When we went to China on these long trips, he would spend weeks in the backwoods and boondocks of that country to get a feel of its people and culture.

Scoop believed that our greatest foreign policy shortcoming in the postwar period was the failure to perceive the Sino-Soviet split, partly as a result of the McCarthy era’s discrediting of China experts. It was his wish that there be an institution to bring together academic expertise on China and Russia to build an intelligent and informed Asia policy. This wish became the inspiration for our founding of NBR after his death.

Kenneth B. Pyle is the Henry M. Jackson Professor Emeritus at the University of Washington and founding president of the National Bureau of Asian Research.