South Korea: The Challenges of a Maritime Nation

This analysis examines South Korea’s maritime security situation, surveying unresolved issues with neighbors—China, Japan, and North Korea—and reviewing Seoul’s contributions to global maritime security.

The spotlight on South Korean security typically shines brightest on concerns over North Korea’s nuclear and ballistic missile programs along with its large conventional forces. Often overlooked are the many maritime issues and security challenges that the Republic of Korea (ROK) faces. Indeed, a cursory look at a map provides a stark reminder that, when including the demilitarized zone (DMZ) as a hard border, South Korea is essentially an “island” with over 2,400 kilometers of coastline. Moreover, in 2018, 44% of the ROK economy was derived from exports that are carried mostly over sea by container ship.[1] Thus, it should be no surprise that South Korea is a maritime nation with important interests as well as worries in the maritime domain. This analysis will address the ROK’s chief concerns with key players in the region—China, Japan, and North Korea—and will conclude by examining its contributions to global maritime security.

CHINA

South Korea and China have a complex relationship. Economic ties with China are very important to the ROK’s prosperity. South Korea’s trade with China accounts for more than the combined total of its trade with the United States and Japan. Yet, South Koreans are also wary of Chinese power and a possible clash of ROK and Chinese interests. Among the sources of friction are ongoing disputes in the maritime domain, particularly those that stem from unresolved demarcation lines with China in the Yellow Sea (known as the West Sea in South Korea).

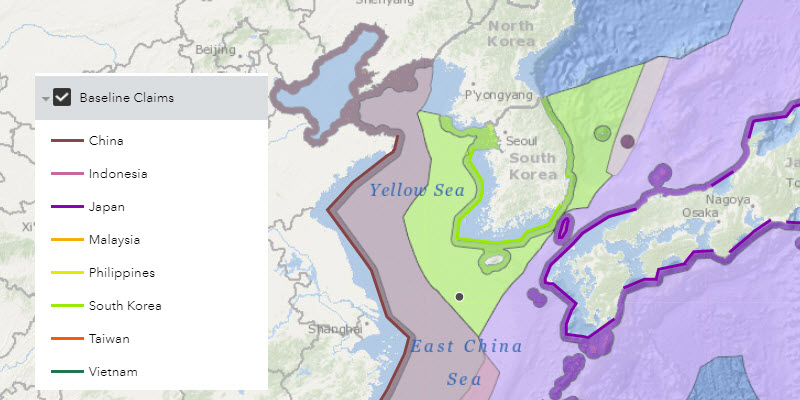

After ratifying the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) in 1996, both countries declared a 200 nautical mile (nm) exclusive economic zone (EEZ), which resulted in significant overlap of the Chinese and South Korean zones. Over the years, Beijing and Seoul have held multiple rounds of meetings to conclude a delimitation agreement, but negotiations have been unsuccessful to date. South Korea maintains that the boundary should be determined by the median line principle (UNCLOS, Article 15) drawn equidistant from the baselines of the concerned states. However, China has argued that the line should be proportional with consideration for China’s larger population and longer coastline.

View of baseline claims and estimated maximum EEZ claims from the Maritime Awareness Project’s interactive map. (Dark shading is the Territorial Sea, and lighter shaded areas are the EEZ claims.)

The lack of a delimitation agreement has generated a related problem concerning illegal fishing. Having overfished its domestic waters, the Chinese fishing fleet must venture farther out to meet growing demand, and vessels regularly cross illegally into South Korean waters, including incursions into South Korea’s 12 nm territorial sea. Without a final EEZ agreement, China and South Korea have managed fishing arrangements through a series of temporary measures that designate fishing zones, set catch limits, and establish quotas for the number of boats allowed in each country’s zone. In November 2018, they reached another fishing pact that establishes rules for both sides.[2]

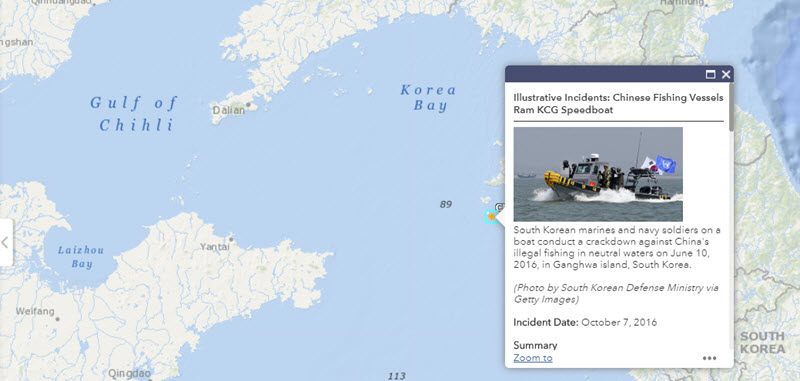

Despite these agreements, illegal fishing—almost solely by Chinese boats around South Korea—has remained a problem. Chinese encroachment has been a regular occurrence over the past ten to fifteen years and in 2018, over one thousand Chinese fishing vessels were chased out of ROK waters.[3] A 2014 ROK estimate calculated that illegal Chinese fishing costs South Korea $1.2 billion.[4] In addition, Chinese navy and coast guard vessels have also crossed into South Korean territorial waters under the guise of policing their fishing fleet. Efforts by the ROK Coast Guard to confront Chinese fishing boats have often turned violent with several ROK Coast Guard crew members and Chinese fishermen killed and injured in altercations. The violence has decreased in the past few years, but Chinese incursions remain a serious concern for ROK maritime authorities.

The Maritime Awareness Project’s interactive map with detail on an October 7, 2016, incident in which Chinese fishing vessels rammed a Korea Coast Guard speedboat.

In addition to this ongoing dispute, China has increased its presence in the Yellow Sea in other ways that have troubled South Korea.[5] Take, for example, efforts by Chinese officials to restrain ROK Navy activities in the region. For many years, China and North Korea have used the 124-degrees east longitude line in the Yellow Sea as a maritime demarcation line. In 2013, China’s navy chief, Admiral Wu Shengli, met the ROK’s chief of naval operations, Admiral Choi Yoon-hee, and insisted that this line should also act as a boundary between the responsibilities and operations of the Chinese and South Korean navies. However, the line has no legal standing, and South Korea has refused to acknowledge it given the necessity of operating farther west to monitor North Korean naval activities and patrol for North Korean merchant vessels that might be transporting material for weapons of mass destruction.[6] Moreover, although China has argued for the 124-degree line, Chinese naval vessels are increasingly crossing that boundary as well.

China has also sought to increase its presence in the Yellow Sea by installing buoys in various locations, including within the disputed EEZs. The first buoy was discovered in 2014 with over a dozen more placed in subsequent years. Beijing has argued that the buoys are a network of sensors to observe weather and ocean currents, but ROK officials fear the chief purpose is to monitor naval traffic and gather data on passing ships and submarines. China has also sent an increasing number of survey ships into these areas to monitor naval activities and conduct topographical surveys. There are concerns that China is doing this to strengthen its negotiating position in future EEZ delimitation talks with South Korea.[7]

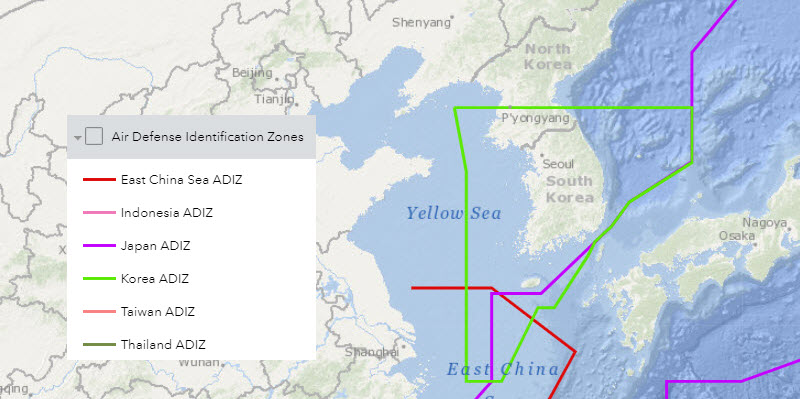

In 2013, China expanded its air defense identification zone (ADIZ), affecting a separate dispute with South Korea and that China calls Suyan Reef.[8] The reef is located approximately 80 nm from the South Korean island Marado, about 70 nm closer than the nearest Chinese island. It is crucial to note that while the Korean name identifies the feature as an island—“do” is Korean for island—both Seoul and Beijing agree that the feature does not meet that definition under UNCLOS, as it is submerged several meters at low tide. Thus, the issue is not considered a territorial dispute. The South Korean government maintains that Socotra Rock should be within its jurisdiction since the feature is located much closer to the Korean Peninsula than China and is part of its continental shelf.[9]

View of ADIZs from the Maritime Awareness Project’s interactive map.

Since the 1950s, South Korea has asserted jurisdiction over Socotra Rock, and in 2003 it constructed the Ieodo Ocean Research Station on the feature to observe weather, ocean currents, and fishing stocks. Chinese authorities have argued that building the facility is illegal since the reef falls within their disputed EEZs and should not have occurred until the dispute was settled. South Korea has countered that construction of the facility was permissible since Socotra Rock is located on its continental shelf, an argument that ROK advocates note is supported by Articles 60 and 80 of UNCLOS, which allow for building structures and installations within a state’s EEZ or on its continental shelf.[10]

In 2013, concerns for jurisdiction over Socotra Rock resurfaced when China extended its ADIZ in the East China Sea. Most attention focused on the inclusion of the disputed islands that Japan calls the Senkaku Islands and China calls the Diaoyu Islands. However, the new zone also encompassed Socotra Rock, and South Korea promptly expanded its ADIZ to include the reef.[11]

JAPAN

ROK-Japan relations are at their lowest point in years, largely due to unresolved historical issues stemming from the 1910–1945 Japanese occupation, which have now veered into trade, economics, and intelligence sharing. Less well known is a maritime dispute over a group of islets, internationally termed the Liancourt Rocks, which the Koreans call Dokdo and the Japanese call Takeshima. The islets are approximately midway between South Korea and Japan. Under UNCLOS (Article 121) and affirmed in the 2016 Permanent Court of Arbitration ruling in the case of the Philippines vs. China, they would be considered rocks that are not entitled to a 200 nm EEZ but only to a 12 nm territorial sea because they “cannot sustain human habitation or economic life of their own.”

Though the claims of both sides go back several hundred years, the core of the dispute began in 1905. Japan maintains it had re-established sovereignty over the islets in February 1905 prior to the establishment of its protectorate over Korea in November 1905. South Korea disagrees, arguing that their sovereignty had long been established over Dokdo/Takeshima. Thus, Japan’s annexation was illegal and did not establish sovereignty, requiring Tokyo to return the islets after World War II. Early versions of the Treaty of San Francisco (1951) that formally ended the war included mention that Dokdo/Takeshima be returned to Korea, but the final version omitted a specific listing of Dokdo creating confusion and uncertainty over their status. Nonetheless, in 1952, President Syngman Rhee announced a “peace line” that drew a maritime boundary that in many places far exceeded the accepted limits of territorial waters and included Dokdo/Takeshima. In 1954, South Korea occupied Dokdo/Takeshima and built a lighthouse, a dock, and barracks for 50 personnel. Twice a year, the ROK military holds exercises in the vicinity of the islets to demonstrate its capability and resolve to defend it.[12] Though Japan protests these exercises and continues to maintain its claim to Takeshima, the likelihood of Japan mounting a military operation to retake the islets is almost nil. However, the dispute is unlikely to be settled anytime soon and remains a part of two countries’ difficult and complicated relationship. Along with continued friction over unresolved historical issues, the Dokdo/Takeshima dispute adds another obstacle to trilateral security cooperation that Washington seeks with these two allies.

NORTH KOREA

Over the years, South Korea’s most deadly maritime challenge has been the disputed boundary with North Korea in the Yellow Sea known as the Northern Limit Line (NLL). The line was drawn shortly after the conclusion of the Korean War armistice. Negotiations settled on a land ceasefire line and the DMZ, but the two sides were unable to agree on maritime boundaries due to disagreements over territorial seas. North Korea insisted on 12 nm while the United States and South Korea maintained it should be only 3 nm. Today, the standard is 12 nm, but at the time 3 nm was the accepted demarcation for territorial seas.

Soon after, it became clear that a maritime boundary was necessary and according to contemporaneous accounts, on August 30, 1953, UN commander general Mark Clark promulgated the NLL. The line is approximately midway between the North Korean coast and five islands controlled by South Korea. However, despite general agreement by researchers on this narrative, the precise document that put forth the NLL has not yet been found.[13] Most likely, the order to establish the line was a routine, low-level operations order that few expected to carry the significance and permanence it does today. South Korea maintains that the NLL is the de facto maritime boundary between the North and South, but North Korea has challenged the line as “bogus” and “illegitimate.”

The NLL has often been a site for violence between the two Koreas. In 1999, 2002, and 2009, the South and North Korean navies clashed with ships sunk and sailors killed on both sides. Hostilities reached an apex in 2010 when a North Korean submarine torpedoed the ROK corvette Cheonan in March off the waters of Baengnyeongdo, South Korea’s northern-most island, killing 46 ROK sailors. In November of that same year, North Korean artillery opened fired on the ROK island Yeonpyeongdo, killing two civilians and two marines while wounding over a dozen others. North Korea had complained that a pending ROK artillery exercise would infringe on its territorial waters. However, the exercise was directed to the seas southwest of the NLL. ROK artillery responded to the North’s shelling and over 170 artillery rounds were exchanged in the clash. Since that time, the NLL has been relatively quiet, though North Korean fishing boats often cross the line illegally.

The issue of the NLL resurfaced in the Panmunjom Peace Declaration that concluded the historic April 2018 inter-Korean summit between Kim Jong-un and Moon Jae-in by calling for the creation of a “maritime peace zone in order to prevent accidental military clashes and guarantee safe fishing activities.”[14] These issues were also included in the Comprehensive Military Agreement signed by both Koreas’ defense officials on September 19, 2018. However, little progress has been made to implement these goals. Until the security situation in the region improves, the NLL is likely to remain as it is.[15]

THE ROK NAVY’S CONTRIBUTIONS TO INTERNATIONAL MARITIME SECURITY

In 2001, ROK president Kim Dae-jung committed South Korea to building an ocean-going navy, and in the years that followed the ROK Navy has added three classes of destroyers, including three Aegis ships along with two large-deck helicopter amphibious assault ships (LPH). South Korea has plans to build three more Aegis destroyers and another LPH. ROK shipbuilding has also included new lines of coastal patrol ships, frigates, and submarines. All these vessels have been built in ROK shipyards, an impressive feat in its own right.

The growth of an oceangoing naval capability has allowed Seoul not only to address regional maritime challenges but also to contribute to international efforts to promote maritime security. In 2009, South Korea deployed its first contingent to the counterpiracy operation, Combined Task Force 151 (CTF-151), the U.S.-led task force that conducts patrols of the Gulf of Aden and waters off the coast of Somalia. Named the Cheonghae Unit, the ROK contribution includes a destroyer and a contingent of ROK SEALs. South Korea also has held the rotating command responsibilities of CTF-151 on a few occasions and received high marks for its command and operational skills.

South Korean Navy sailors salute during a ceremony marking the launch of the “Cheonghae” unit consisting of a 4,500-ton destroyer with 270 crew, a helicopter and 30 special forces in southeastern port city of Busan on March 3, 2009. (Choi Jae-Ho/AFP via Getty Images)

Over the past year, U.S. tensions with Iran have escalated and security concerns have increased in the Strait of Hormuz with Iran’s seizure of a British oil tanker. The Trump administration has responded to this incident with calls for organizing an allied naval coalition to protect these waters from further incident. During a trip to Seoul in July, then national security adviser John Bolton asked for South Korea’s assistance in this effort, and South Korea continues deliberations on how it might support the U.S. mission. [16] The request is a difficult issue for South Korea. While securing these shipping lanes and supporting U.S. efforts, particularly with the next round of alliance burden-sharing talks underway, are important, South Korea has also sought to maintain good relations and economic ties with Iran that include imports of Iranian oil.

Over the past two decades, the ROK Navy has gone from a coastal defense force focused on North Korea to an oceangoing navy with a broader set of capabilities. During this time, South Korea has modernized its navy and balanced the requirements of coastal defense with a fleet that can help protect commercial interests as well as contribute to multilateral maritime security operations.

CONCLUSION

South Koreans live in a challenging security environment. Most attention has been focused on North Korea and the dangers on land. Yet, South Korea also faces serious maritime challenges that require a balancing act between many competing priorities. Security in Northeast Asia is likely to become increasingly complex and uncertain in the years ahead. South Korea will face some difficult choices navigating the possibility of increased competition among the major powers, which will further elevate its role as a maritime nation.

Terence Roehrig is Professor of National Security Affairs and the Director of the Asia-Pacific Studies Group at the U.S. Naval War College. All views expressed here are solely his own, and do not represent the official position of the U.S. Navy, the U.S. Department of Defense or the U.S. government.

Download a pdf version of this analysis piece here.

ENDNOTES

[1] “Export of Goods and Services (% of GDP), Rep. of Korea,” World Bank, 2018, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NE.EXP.GNFS.ZS?locations=KR.https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NE.EXP.GNFS.ZS?locations=KR

[2] “S. Korea, China Reach 2019 Fisheries Agreement,” Yonhap, November 9, 2018, https://en.yna.co.kr/view/AEN20181109006000320.

[3] Wooyoung Lee, “Chinese Vessel Caught Illegally Fishing in South Korea,” UPI, November 26, 2018, https://www.upi.com/Top_News/World-News/2018/11/26/Chinese-vessel-caught-illegally-fishing-in-South-Korea/7511543215895.

[4] Kwang-Nam Lee and Jin-Ho Jung, “Estimating the Fisheries Losses Due to Chinese Illegal Fishing in the Korean EEZ,” Journal of Fisheries Business Administration 45, no. 2 (2014): 73–83.

[5] I am indebted to Lieutenant Commander Lim Jihye of the ROK Navy for some very valuable insights on these issues involving China.

[6] Jeong Yong-su, “China Tried Muscling South Korea in the Yellow Sea,” JoongAng Daily, November 30, 2013, http://koreajoongangdaily.joins.com/news/article/article.aspx?aid=2981288.

[7] “S. Korean Military Keeps Monitoring China’s Installation of Buoys: Ministry,” Yonhap, September 14, 2018, https://en.yna.co.kr/view/AEN20180914008000315.

[8] Chico Harlan, “China Creates New Air Defense Zone in East China Sea amid Dispute with Japan,” Washington Post, November 23, 2013, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/china-creates-new-air-defense-zone-in-east-china-sea-amid-dispute-with-japan/2013/11/23/c415f1a8-5416-11e3-9ee6-2580086d8254_story.html.

[9] “S. Korea Protests China’s Jurisdictional Claim on Ieodo,” Yonhap, March 12, 2012, https://en.yna.co.kr/view/AEN20120312008300315.

[10] “No Territorial Dispute,” Korea Herald, March 13, 2012, http://www.koreaherald.com/view.php?ud=20120313000457&cpv=0.

[11] Choe Sang-Hun, “South Korea Announces Expansion of Its Air Defense Zone,” New York Times, December 8, 2013, https://www.nytimes.com/2013/12/09/world/asia/east-china-sea-air-defense-zone.html.

[12] Jihye Lee and Gearoid Reidy, “South Korea Holds Military Drills at Islets Disputed with Japan,” Bloomberg, August 24, 2019, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2019-08-25/south-korea-starts-military-training-in-disputed-islets.

[13] Terence Roehrig, “The Origins of the Northern Limit Line: Another Piece of the Puzzle,” NK News, January 12, 2017, https://www.nknews.org/2017/01/the-origins-of-the-northern-limit-line-another-piece-of-the-puzzle.

[14] “Panmunjom Declaration for Peace, Prosperity and Unification of the Korean Peninsula,” April 27, 2018, available at https://uk.reuters.com/article/uk-northkorea-southkorea-summit-statemen/panmunjom-declaration-for-peace-prosperity-and-unification-of-the-korean-peninsula-idUKKBN1HY193.

[15] “Agreement on the Implementation of the Historic Panmunjom Declaration in the Military Domain,” September 19, 2018, https://www.ncnk.org/sites/default/files/Agreement%20on%20the%20Implementation%20of%20the%20Historic%20Panmunjom%20Declaration%20in%20the%20Military%20Domain.pdf.

[16] Lee Chi-dong, “S. Korea Mulls over Its Military Role in Strait of Hormuz,” Yonhap, December 13, 2019, https://en.yna.co.kr/view/AEN20191213002200315

Banner image source: © South Korean Defense Ministry via Getty Images. In this handout provided by the South Korean Defense Ministry, South Korean marines and navy soldiers on a boat conduct a crackdown against China’s illegal fishing in neutral waters on June 10, 2016 in Ganghwa island, South Korea.

South Korea in a Challenging Maritime Security Environment

South Korea in a Challenging Maritime Security Environment