Essay in NBR Special Report 110

Strategic Competition in Melanesia

Centering Local Perspectives for Successful U.S. Engagement

This is the Introduction to the report “Navigating Strategic Pathways in Melanesia: Options for U.S. Engagement.”

Over the next decade, Pacific Island nations will face many challenges. Potential solutions will rely, at least in part, on the policy decisions of countries outside the region. Climate change impacts are already occurring, and Pacific Island leaders are proposing various resilience initiatives.[1] The United States has called for “elevating broader and deeper engagement with the Pacific Islands as a priority of U.S. foreign policy” and committed to “working together with the Pacific, and to do so according to principles of Pacific regionalism, transparency, and accountability.”[2] External partners, such as those associated with the Commonwealth, have vowed to support resilience in a way “that transcends the pillars of humanitarian, development, human rights, peace, and security.”[3] Australia, New Zealand, Japan, France, South Korea, and India have also proposed updated engagement strategies for the region.[4]

Yet, despite increased interest in the Pacific, U.S. presence and engagement remain nascent in Melanesia. For the U.S. policy initiatives to be successful, engagement will need to be consistent, and programs should be collaborative if the United States is to achieve the goals of the Pacific Partnership Strategy. Unlike Micronesia, which has long-standing relationships with the United States, Melanesia represents unique security, development, and foreign policy challenges, and coordination is more complex.[5]

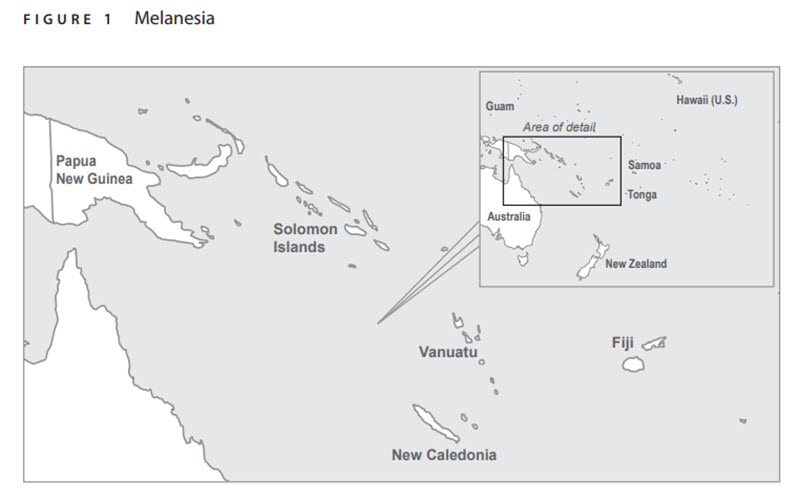

Melanesia is both a geographic region and subregion of the Pacific Islands (see Figure 1), as well as an organizational concept. Despite commonalities across the Pacific Islands region, the countries and communities throughout Melanesia, Micronesia, and Polynesia are not homogenous. Melanesia is particularly diverse in geography, ethnic groups, religious beliefs, customs, and communal systems of organization. Security and stability issues are complicated and often difficult to penetrate for those unfamiliar with the region’s history, culture, and politics. Like in the rest of the Pacific, critical challenges for Melanesia also include climate change, resource constraints, illegal fishing, food security, environmental sustainability, crime, and trafficking. Internal security challenges have the potential to exacerbate these region-wide concerns.

Debates in Washington, Canberra, and Beijing have centered on elements of strategic competition. This report, however, explores key security issues in Melanesia from the perspective of local scholars alongside the perspectives of several U.S. contributors. Collectively, the six essays examine Melanesia’s unique security challenges; assess the impact of strategic competition on countries, governments, and communities; and explore options for how Melanesian nations can manage increased attention from external actors.

This introductory essay serves to highlight the views of Pacific Island representatives, especially those from Melanesia, and explain how Melanesian experts and Pacific Islands–based scholars conceptualize those challenges. The findings presented in this introduction are based in large part on a Track 1.5 dialogue held in April 2023 in Nadi, Fiji.[6] The National Bureau of Asian Research (NBR) convened the 2023 Pacific Islands Strategic Dialogue, with support from the Defense Threat Reduction Agency’s Strategic Trends Research Initiative and the University of the South Pacific, to explore security challenges and perspectives on strategic competition. The dialogue brought together 25 officials, regional experts, and scholars in a hybrid format. NBR asked participants to consider the following questions:

- How are military and security posture changes by the United States, Australia, China, and other countries perceived by Pacific Island countries, especially governments, leaders, and citizens in Melanesia?

- How are Melanesian governments, organizations, and citizens reacting to U.S.-China strategic competition? What are the implications for Melanesia of regional crises?

- What role should the United States and its allies’ militaries play in Melanesia over the next five to ten years? In what areas can security and defense relationships be strengthened, and how?

Before summarizing the findings from the dialogue, I offer some framing remarks that may be useful for a U.S. audience. For those in the Pacific, this background is likely common knowledge. In the United States, however, despite increased attention on the Pacific Islands region, especially from the U.S. government, there is still much to be learned about individual countries in the Pacific and the region more generally. Geographic and cultural boundaries and discussion of subregions are helpful shorthand to understand the differences within the Pacific Islands region, but those generalizations sometimes overshadow the complexity that exists. It is impossible to do justice to the full complexity of this region here, so I concentrate on two central themes: diversity and security.

Key Concepts: Diversity and Security in Oceanic History

Neither diversity nor security are agreed-on concepts; each word means something vastly different depending on the audience. Melanesian individuals, communities, national governments, and regional organizations use these concepts to refer to many distinct ideas. In the United States, scholars often begin with the individual or the nation-state as the unit of analysis for international relations. In Melanesia, by contrast, scholars and practitioners often begin with communities, real and imagined, as the focal point for understanding the issues these nation-states face.

The Pacific Islands region is diverse, but that diversity is often underappreciated. First, regional knowledge remains limited and has historically focused on Polynesia or Micronesia. During the Cold War, the Peace Corps and other U.S. government agencies were active in the region, but over time those programs diminished in size and scope. By 2022, only four countries in the region had Peace Corps programs, down from thirteen at the height of U.S. presence in the region.[7] Second, post–Cold War U.S. foreign policy has focused on managing conflict in Europe and the Middle East, as the current conflicts between Russia and Ukraine and Israel and Hamas illustrate. In our previous Micronesia report, we noted that throughout the 1990s and 2000s, many Pacific Islanders viewed U.S. foreign policy toward the Pacific Islands as a period of benign neglect. Third, because of the relative cultural connectivity of Polynesia, there is an implicit assumption that Pacific Islanders share the same history, languages, worldviews, religions, and social practices. This perception masks the diversity within particular countries and within the Melanesian and Micronesian subregional groupings.

Melanesia is culturally, linguistically, and geographically diverse. For example, in the 900-plus islands in the Solomon Islands archipelago, there are approximately 80 languages spoken.[8] According to Teaching Oceania, an introductory series created by the Center for Pacific Islands Studies at the University of Hawai’i at Mānoa, a location such as “New Guinea became one of the most linguistically diverse places in the world, with more than 800 distinct Papuan languages.”[9] Cultural practices also affected the history of regional organizations, such as the Melanesian Spearhead Group (MSG), as discussed by Ilan Kiloe in his essay for this report. Likewise, William Waqavakatoga describes the role of religious beliefs in foreign policy in the region. There is not sufficient space here to cover all the many forms of regional diversity, so I simply want to emphasize that cultural homogeneity does not exist in Melanesia. Foreign diplomats must take the time to familiarize themselves with the different geographies, national and ethnic histories, languages, religions, and cultural practices within the region. Homogeneity should not be assumed, and steadfast study will be necessary.

Diversity has brought positive benefits to the region, but it has also been a challenge for regional unity. Global challenges, such as climate change, have necessitated regional unity for Pacific Island nations to influence the global discourse,[10] but solutions to Pacific problems do not occur quickly. Pacific Islanders have successfully built platforms for shaping the international discourse on climate change; illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing; nuclear testing; and seabed mining. Yet, because of the diversity in the region, the Pacific Islands Forum has not been able to address all concerns, and subregional organizations, such as the MSG, Micronesian Chief Executives, and the Polynesian Leaders Group remain important. Regional leaders are not monolithic but understand the need for compromise to achieve collective action.[11]

Conceptions of security in the Pacific Islands differ from how security is conceptualized in the United States or Europe. Human-centered security is national security. During dialogue events and consultations in 2023, I heard at least ten different definitions of security that varied based on whether the speaker was starting from the perspective of the individual, community, country, or region. Citizens and civil society organizations convey collective goals to ensure that local voices are heard by national and international leaders. Efforts to fight climate change reflect this need. Yet, there is also a danger in securitizing every issue or making everything a “national security” concern. In China, for example, many aspects of governance have become “securitized,”[12] and this model has led to a security dilemma with the United States and other advanced industrial economies.[13]

Pacific conceptions of security are neither “hard security” as typically understood in the United States,[14] nor the all-encompassing security that has emerged in Xi Jinping’s China.[15] Pacific security is more closely linked to human-centered security as it emerged in Southeast Asia,[16] but with a uniquely Blue Pacific lens.[17] The Boe Declaration on Regional Security expressly notes that Pacific leaders “affirm an expanded concept of security which addresses the wide range of security issues in the region, both traditional and non-traditional, with an increasing emphasis on human security, including humanitarian assistance, to protect the rights, health and prosperity of Pacific people.”[18] Pacific leaders recognize the need to create prosperity while building resiliency. If communities and the individuals who make up those communities are not healthy and safe, then security does not exist.

Dialogue Findings

The security issues in Melanesia are complex and contested, presenting challenges and opportunities for U.S. foreign and defense policy. Melanesia has both political significance and a geographic status, as discussed above, but the immense diversity of the subregion means that it is difficult to generalize. This section emphasizes four main findings from the 2023 dialogue while acknowledging that those views are not necessarily representative of all Melanesian perspectives. We sought a diverse group of participants, but even within our group of academics, experts, scholars, and practitioners, there was significant disagreement on which issues were most profound or in need of solutions.

First, Melanesian countries face significant domestic development challenges and view “incomplete nation-building” as their primary security concern. Unfinished decolonization continues to hamper the creation of coherent national identities. Because domestic development and internal security challenges remain stark, participants noted that Melanesian countries must welcome all forms of aid—from all external partners. Rather than limit their choices, countries in the region want to engage all development partners. One dialogue participant put the matter quite simply: “If the Belt and Road Initiative is an option, they are going to take it” because “building roads, bridges, and airports…are tangible developments everyday people can see.” This is the lens through which many see the development realities. Thus, strategic competition that could limit choices in either foreign or domestic policy is viewed as problematic.

Second, Melanesian countries and their leaders want to maintain strategic autonomy. Some participants noted that if strategic competition does not center on local needs, priorities, and preferences—or if engagement does not include local stakeholders that appreciate on-the-ground realities—such competition could negatively affect domestic interests. In this context, participants raised several related issues, including duplicative foreign aid, lack of coordination among donors, absorptive capacity of governments, and wasted resources. Critically, there is also concern that the media focus on U.S.-China strategic competition is drowning out Melanesian and Pacific voices. While we are grateful to this volume’s contributors from locations such as Papua New Guinea, Vanuatu, and Fiji, much more needs to be done to ensure local voices are reflected in U.S. debates about foreign policy for the Pacific. As I wrote in the report on Micronesia, in the United States we can do better.[19]

Third, Melanesian countries view China as a development partner. The People’s Republic of China (PRC) has provided economic and development assistance, and the average citizen views new infrastructure as positive and welcomes the partnership. Dialogue participants, and several of the contributors to this report, argue that the basic needs of citizens are often secondary to foreign policy. Yet, despite welcoming Chinese aid and official development assistance, participants were realistic about both the positive and negative aspects of China’s engagement in the region. Several dialogue experts noted that Melanesian citizens and their leaders believe that the PRC needs to improve its knowledge of internal country dynamics. The criticisms of Chinese aid have raised additional questions about the overall efficacy of development assistance from all external actors operating in the Pacific.[20] Policymakers and scholars should dedicate additional attention to research on aid, development outcomes, and perceptions of aid.

Fourth, regional leaders believe that Pacific voices need to maintain solidarity. If regional organizations, such as the Pacific Islands Forum, are not cohesive, dialogue participants worried that Pacific leaders may have less capacity to shape the global agenda on critical issues like climate change or other emerging topics. Internally, colonial legacies created contested identities and subregional realities that require country or Melanesian-specific solutions. The MSG, created out of the legacy of decolonization, has been called on to address key internal security challenges, even though the organization was originally meant to become a vehicle for economic cooperation.[21]

Understanding Melanesia in the United States

This report includes essays written by scholars from Fiji, Papua New Guinea, Vanuatu, and New Zealand, as well as by contributors representing U.S. perspectives. The first essay, written by Patrick Kaiku and Vernon Gawi, describes how Melanesian states, in particular Papua New Guinea, are navigating nation-building and political modernization amid great-power rivalry. Despite serious internal security challenges, Kaiku and Gawi offer suggestions for how Melanesian countries might take advantage of strategic competition to build an informed citizenry and better institutional capacity. In the next essay, Ilan Kiloe discusses how the Melanesian Spearhead Group came into existence and how internal security challenges have affected the organization’s evolution. While domestic security and development challenges remain, Kiloe notes how the MSG shapes subregionalism in the Pacific. This is critical knowledge for U.S. policymakers who may be working in these countries or alongside these organizations. Next, the report turns its attention to Solomon Islands, which is a site for competing security stakeholders to achieve their own goals. Anna Powles describes how Australia and China are attempting to provide security assistance and finds that competition could have disruptive consequences.

Moving from assessments of the situation to policy options for engagement, William Waqavakatoga of the University of Adelaide addresses how religious traditions, in particular Christianity, may offer a pathway for diplomatic engagement. He considers the use of cultural and religious traditions by Pacific leaders themselves and explains how that element of diplomacy could build trust and establish a foundation for long-term engagement. Shifting to the U.S. perspective, Yan Bennett expands the discussion for U.S. policymakers by describing the necessity of reframing U.S. perceptions of China in Melanesia while simultaneously increasing U.S. diplomatic engagement across governance, economic, and security programs. Margaret Sparling then describes how specific investments by the United States, particularly in media and information technology connectivity, could have an outsized impact on regional security in Melanesia. The report concludes with Miles Monaco and Darlene Onuorah’s summary of policy options derived from the dialogue itself.

Pacific Island nations are not small, weak, isolated, or lacking in agency. The Blue Pacific concept expressly counters these “disempowering narratives” by emphasizing alternative perspectives, regionalism, and collection action.[22] U.S. policy toward the Pacific should be informed by regional narratives and acknowledge them where appropriate.[23] As discussed in the report on Micronesia, “appreciating the concerns of Pacific Island country leaders is not simply agreeing with them or using their rhetoric.”[24] One set of scholars argues that there is a danger that “strategic narratives may be appropriated,”[25] so the United States and Partners in the Blue Pacific must be cognizant of these potential concerns. To avoid appropriation while advocating for mutual interests, the United States must actively coordinate with Pacific Island leaders in advance of major policy announcements. These options will be discussed further in the report’s conclusion. Active coordination will require strategic patience from U.S. policymakers, but remaining committed to Pacific regionalism is a central tenet of the Pacific Partnership Strategy. U.S. policy announcements should be delayed until proper consultation has occurred with the relevant Pacific partners. Coordination will take presence, patience, consultation, and a long-term pledge to engagement with Melanesia and the broader Pacific Islands region from the United States. But that commitment is one worth making.

April A. Herlevi is a Nonresident Fellow at the National Bureau of Asian Research.

Endnotes

[1] Pacific Islands Forum Secretariat, “Special Forum Economic Ministers Meeting Action Plan,” July 2019. During this meeting, the economic ministers “considered and discussed the revised governance arrangements of the Pacific Resilience Facility.”

[2] White House, Pacific Partnership Strategy of the United States (Washington, D.C., September 2022), 4, 5, https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/Pacific-Partnership-Strategy.pdf.

[3] “Samoa Announces Theme for the 2024 Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting,” Commonwealth, Press Release, September 21, 2023, https://thecommonwealth.org/news/samoa-announces-theme-2024-commonwealth-heads-government-meeting.

[4] Joanne Wallis, Maima Koro, and Corey O’Dwyer, “The ‘Blue Pacific’ Strategic Narrative: Rhetorical Action, Acceptance, Entrapment, and Appropriation?” Pacific Review 37, no. 4 (2024): 797–824.

[5] For analysis of U.S. engagement with Micronesia, see April A. Herlevi, ed., “Charting a New Course for the Pacific Islands: Strategic Pathways for U.S.-Micronesia Engagement,” National Bureau of Asian Research, NBR Special Report, no. 104, March 2023, https://www.nbr.org/publications/charting-a-new-course-for-the-pacific-islands-strategic-pathways-for-u-s-micronesia-engagement.

[6] The Melanesia-focused dialogue included three keynote addresses, four substantive panels, and two interactive sessions. Discussions at the 2023 Pacific Islands Strategic Dialogue built on a Micronesia-focused dialogue held in 2022. See Herlevi, “Charting a New Course for the Pacific Islands.”

[7] “Congressional Letter to the Acting Director of the Peace Corps,” July 19, 2022, https://www.markey.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/letter_to_peace_corps_acting_director_on_the_pacific_islands.pdf.

[8] Kabini Sanga and Martyn Reynolds, “Waka hem no finis yet: Solomon Islands Research Futures,” Pacific Dynamics: Journal of Interdisciplinary Research 6, no. 1 (2022): 30–49.

[9] Alexander Mawyer, ed., Introduction to Pacific Studies, Teaching Oceania 6 (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i at Mānoa, 2020), 27. See Image 11 for a map of the language families in Papua New Guinea. The Teaching Oceania series, compiled jointly by the Center for Pacific Islands Studies and the University of Hawai’i at Mānoa Library, provides extensive open-access materials on topics such as health, the environment, nuclear testing, gender, voyaging, and many other topics within Pacific Studies. The Teaching Oceania volumes are available at https://hdl.handle.net/10125/42426.

[10] Greg Fry and Sandra Tarte, eds., The New Pacific Diplomacy (Acton: ANU Press, 2015).

[11] Gonzaga Puas, “The Proposed Withdrawal of Micronesia from the PIF: One Year Later,” Department of Pacific Affairs, Australian National University, March 25, 2022, https://openresearch-repository.anu.edu.au/server/api/core/bitstreams/a5aad122-f9f0-4438-b542-dcd040665d6b/content.

[12] Sheena Chestnut Greitens, “Xi Jinping’s Quest for Order: Security at Home, Influence Abroad,” Foreign Affairs, October 3, 2022.

[13] Margaret M. Pearson, Meg Rithmire, and Kellee S. Tsai, “China’s Party-State Capitalism and International Backlash: From Interdependence to Insecurity,” International Security 47, no. 2 (2022): 135–76.

[14] Pacific scholars often refer to these types of debates as “militarism” rather than security. See Monica C. LaBriola, ed., Militarism and Nuclear Testing in the Pacific, Teaching Oceania 1 (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i at Mānoa, 2019).

[15] Sheena Chestnut Greitens, “National Security after China’s 20th Party Congress: Trends in Discourse and Policy,” China Leadership Monitor, Fall 2023, https://www.prcleader.org/post/national-security-after-china-s-20th-party-congress-trends-in-discourse-and-policy.

[16] Amitav Acharya, “Human Security: East versus West,” International Journal 56, no. 3 (2001): 442–60.

[17] Pacific Islands Forum Secretariat, 2050 Strategy for the Blue Pacific Continent (Suva, July 2022), https://forumsec.org/sites/default/files/2023-11/PIFS-2050-Strategy-Blue-Pacific-Continent-WEB-5Aug2022-1.pdf; Pacific Islands Forum, “Action Plan to Implement the Boe Declaration on Regional Security,” 2019, https://forumsec.org/sites/default/files/2024-03/BOE-document-Action-Plan.pdf; and Pacific Islands Forum, “Boe Declaration on Regional Security,” 2018, https://forumsec.org/publications/boe-declaration-regional-security.

[18] Pacific Islands Forum, “Action Plan to Implement the Boe Declaration on Regional Security,” Section 7.

[19] April A. Herlevi, “Beyond Presence: What Can the United States Do Better in the Pacific?” in Herlevi, “Charting a New Course for the Pacific Islands.”

[20] Meg Taylor and Soli Middleby, “More of the Same Is Not the Answer to Building Influence in the Pacific,” 9DASHLINE, October 3, 2022. https;//www.9dashline.com/article/more-of-the-same-is-not-the-answer-to-building-influence-in-the-pacific; and Meg Taylor and Solstice Middleby, “Aid Is Not Development: The True Character of Pacific Aid,” Development Policy Review 41, no. S2 (2023).

[21] Ilan Kiloe, “Free Trade in the South Pacific: An Overview,” Journal of South Pacific Law 13, no. 1 (2009): 47–55.

[22] Tarcisius Kabutaulaka, “Mapping the Blue Pacific in a Changing Regional Order,” in The China Alternative: Changing Regional Order in the Pacific Islands, ed. Graeme Smith and Terence Wesley-Smith (Acton: ANU Press, 2021), 41–70.

[23] In our analysis of U.S. engagement in Micronesia, we refer to the “three A’s: acknowledge, appreciate, and actively coordinate.” See Herlevi, “Beyond Presence.”

[2] Wallis et al., “The ‘Blue Pacific’ Strategic Narrative,” 20. Italics are my own for emphasis. For more on how the Partners in the Blue Pacific initiative may have been appropriated without consultation of Pacific leaders, see Greg Fry, Tarcisius Kabutaulaka, and Terence Wesley-Smith, “‘Partners in the Blue Pacific’ Initiative Rides Roughshod over Established Regional Processes,” Development Policy Centre, DevPolicy blog, July 5, 2022, https://devpolicy.org/pbp-initiative-rides-roughshod-over-regional-processes-20220705.