Strengthening U.S. Trade Strategy in the Asia-Pacific

The Role for the Korea-U.S. FTA

Charles Boustany Jr. and Clara Gillispie explore what is at stake in the Korea-U.S. FTA renegotiations and discuss key considerations for sustaining U.S. economic competitiveness and leadership in the Asia-Pacific.

The Korea-U.S. Free Trade Agreement (KORUS FTA) is one of the United States’ most ambitious FTAs, and it should rightly be strengthened but not discarded. After a painstaking six-year negotiation process, KORUS significantly lowered barriers to trade between the countries and is one of only two FTAs that the United States has with any country in Asia. It also reflects our highest ambitions for ensuring robust protection for intellectual property (IP) and offers a template for how other countries might develop robust standards for 21st-century trade.

KORUS has now been in effect for over five years. Five years is a useful period for assessing not only how much progress both countries have made toward full implementation of the agreement, but also what impacts it has had overall. While leaders in both countries have seized on some of the agreement’s drawbacks, our own government has been particularly critical of its results. President Donald Trump has expressed concerns that the agreement has not lived up to its ambitious promises and has questioned whether this and other U.S. trade deals are fair and reciprocal. [1]

This commentary explores what is at stake in the KORUS renegotiations and discusses key considerations for sustaining U.S. economic competitiveness and leadership in the Asia-Pacific.

What Is at Stake? U.S. Leadership in the Asia-Pacific

The Asia-Pacific is the most economically dynamic region in the world, and sound engagement is vital to U.S. competitiveness in increasingly integrated global markets. Yet over the past year, the United States has announced a series of policy stances that have begun to undermine our legitimacy in the Asia-Pacific and seemingly backed us into a corner. Actions such as the withdrawal from the Trans-Pacific Partnership, the constant threats to leave the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and KORUS, and recent efforts to implement Section 201 safeguards and Section 232 investigations have all tarnished the United States’ image as the champion of open markets and free trade. Similarly unfortunate is the sequencing of some of these actions—raising tariffs on South Korea and other partners under Section 201 while at the same time touting during KORUS negotiations that all countries benefit from removing tariffs.

These recent activities have sparked concern not only within South Korea but also among observers who are hoping for the United States to advance a forward-looking and comprehensive economic strategy. Ceding ground for U.S. engagement in the region will likely have long-term repercussions as other countries look to fill any vacuum in U.S. leadership. This withdrawal is also occurring at a time when China is expanding its influence in the region and around the world. As noted in a recent essay in the journal Asia Policy, China’s “multi-decade strategy is bearing fruit as Chinese power and interests are beginning to predominate,” while “U.S. regional interests and leadership are challenged, and U.S. economic and security policies relevant to Asia are incoherent.” [2]

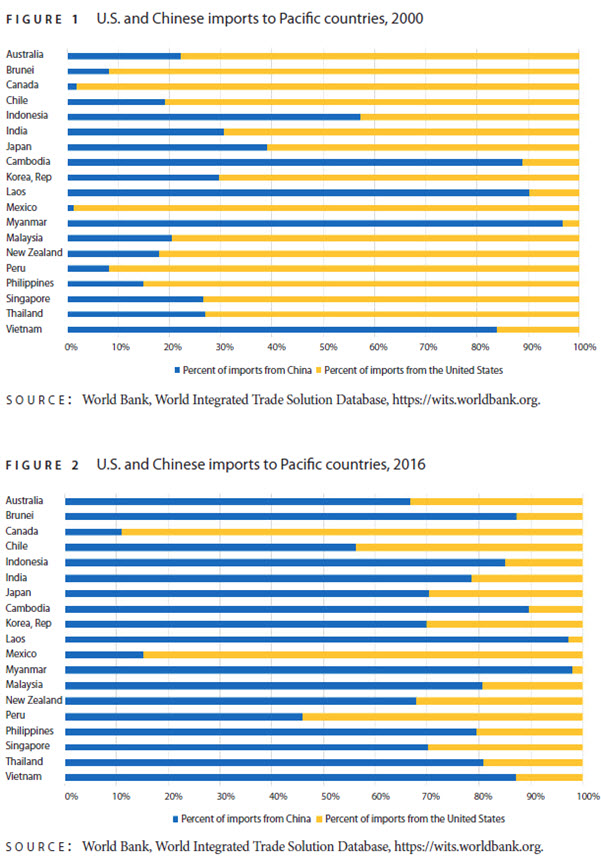

China’s advancement as an economic leader in the Asia-Pacific has been rapidly progressing over the past two decades. Historically South Korea’s largest trading partner, the United States now is second behind China. The balance of exports from the United States and China to South Korea has flipped, with the United States accounting for 70% of South Korean imports from the two countries in 2000 but only 30% in 2016 (see Figure 1 and Figure 2). [3] In fact, among nineteen Asia-Pacific countries, the only markets where the United States maintained a majority of imports in 2016 were Peru, Canada, and Mexico. While this trend can partly be explained by China’s emergence as a major global economy and its proximity to many Asia-Pacific countries, by withdrawing from the region, the United States is ceding even more leadership and standards-setting to China.

KORUS: Getting into the Details

Ultimately, the argument that the United States must stay engaged in regional FTAs to promote U.S. leadership only works to the extent that specific agreements promote U.S. interests. One of the Trump administration’s primary complaints about KORUS is that the agreement has increased the U.S. trade deficit in goods ($27.7 billion in 2016). This concern should not be ignored, but it should be placed in context. First, KORUS has genuinely led to an expansion of Korean imports from the United States—an increase of approximately 3% during 2011–16. [4] This figure sounds insignificant until one notes that South Korea’s overall imports from the world decreased by 22.5% during this same period. [5] Second, part of this deficit in goods is driven by something that should be encouraged in a globalized market: U.S. consumers having greater access to products and other goods, which in turn has boosted U.S. competitive advantages is other areas. Indeed, the United States now has a surplus of $10.7 billion in trade of services with South Korea.

But more specifically, the strength of KORUS is in its details: the high-standards and positive norms from global trade that it promotes. The agreement eliminates 95% of tariffs, and exports of manufactured goods are up 8.4% from levels before it entered into force. It estimated that “for each added billion dollars in exports, roughly 6,000 American jobs are created,” a benefit that is at the center of recent U.S. economic strategy. [6] In addition to the more sweeping benefits of tariff elimination and job creation, KORUS either has already benefitted or has the potential to enhance various industries in the United States.

Intellectual Property. KORUS raised standards for IP and trade secrets protection. This component of the agreement was deemed to be one of the most successful aspects of the original negotiations. By establishing mutually agreed-upon policies for the treatment of IP and trade secrets, the United States and South Korea were creating the “gold standard” for trade. IP theft is a major concern for both countries, which increasingly rely on innovative industries to drive economic growth. As noted by the Commission on the Theft of American Intellectual Property, the cost of counterfeit goods, piracy, and theft of trade secrets to the U.S. economy alone is estimated to exceed $225 billion and could be as high as $600 billion. [7] While some have rightly questioned whether all of the agreement’s IP provisions have been fully realized, this is an area where we should be strengthening our work with South Korea on full implementation—not weakening standards in any new negotiations.

FDI. The investment chapter of KORUS encouraged increased bilateral FDI, and since 2011, South Korean direct investment in the United States has roughly doubled. [8] South Korean companies that have established U.S. offices support almost 52,000 U.S.-based jobs. [9] Protectionist tendencies exhibited by the United States, such as the recent announcement of tariffs on washing machines—which directly affect South Korean industry—threaten this important FDI relationship and could prevent future investments. [10]

Agriculture. Agriculture was one of the more contentious areas of the original KORUS negotiations and continues to be a sensitive issue for both parties. KORUS reopened the South Korean market for U.S. beef and beef products, which had been restricted since 2003. The U.S. beef industry saw an increase in exports of 18.1% from 2011 to 2015 and exported $1.1 billion worth of goods in 2016. [11] Other exports like potatoes and cherries have also seen substantial growth since gaining access to the South Korean market. In Washington State, exports of potatoes and cherries grew 80% and 200%, respectively. [12]

Energy. The Trump administration has rightly indicated that expanding natural gas exports are an important element of how we can promote American competitiveness, and KORUS plays a significant role in realizing this vision. The United States’ legal framework for natural gas exports is guided by the Natural Gas Act, as amended, which considers exports to FTA countries to be in the public interest and that applications should be authorized without modification or delay. [13] For countries with which the United States does not have an FTA, natural gas exports must first be reviewed through a complex, extended process with the Department of Energy and the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission. As the United States transitions to become a net exporter of natural gas, South Korea is also seeking to increase the use of this fuel in its domestic energy mix. Although energy alone is unlikely to eliminate the trade deficit, it can boost U.S. exports while simultaneously bolstering energy security in South Korea.

Where Are We Now?

In light of the many considerations listed above, the outcome of KORUS renegotiations will have a far-reaching impact on U.S. geopolitical and economic influence in the Asia-Pacific and therefore must be monitored closely.

The second round of negotiations concluded on February 1 in Seoul, and by all accounts appears to have been narrow in focus, with discussions centering on investor-state dispute settlements, automobiles, and trade remedies. Public statements from the lead negotiator on the U.S. side, Assistant U.S. Trade Representative Michael Beeman, have largely focused on trade in automobiles. Although U.S. passenger vehicle exports increased from $418 million in 2011 to $1.287 billion in 2015, the South Korean auto industry accounts for 70%–80% of the trade surplus with the United States. [14] The U.S. team wants South Korea to reduce or remove non-tariff barriers to market access for U.S. automobiles, including safety and environmental standards. [15]

The South Korean team is led by Yoo Myung-hee, director-general for the Trade Policy Bureau. His team focused on safeguard measures and anti-dumping tariffs. This was particularly poignant in light of the recent decision by President Trump to implement tariffs on solar panels and washing machines. As noted above, these later tariffs in particular have direct implications for South Korea, even if they were imposed in a broader context than the KORUS negotiations.

The date for the third round of KORUS negotiations has yet to be announced, but it will also be important to track the ongoing NAFTA discussions. Given that it is the first FTA to undergo the Trump administration’s approach to renegotiating trade agreements, many experts and policymakers are looking to NAFTA discussions to predict the outcome of KORUS negotiations. No major advancements have been announced thus far, and any progress will likely be hampered by the campaigns for the upcoming Mexican presidential election in July and U.S. congressional midterms in November.

Moving Forward

As KORUS negotiations continue, there are several key areas that policymakers must consider to ensure a positive outcome. First, modern trade agreements need to keep pace with innovative breakthroughs and advances. Although such technological disruptions occur at a faster pace than FTAs can be negotiated, KORUS must include mechanisms to update and revise sections, particularly pertaining to the growing digital economy.

Second, it is critical for both countries to improve their understanding of the agreement and the benefits it provides. For example, restrictive health technology assessments can impede innovative medical devices from gaining access to the market, with negative consequences for public health. More transparent dialogue may reduce uncertainties that were initially responsible for boundaries.

Finally, it is imperative that the United States not abandon its allies. Security and economics cannot be separated, and KORUS is at heart a landmark agreement for engagement that was built on decades of security cooperation and shared values. Reneging on an agreement with a staunch ally does not inspire confidence for other countries with which the United States may be seeking to negotiate future trade agreements.

Endnotes

[1] Office of the U.S. Trade Representative (USTR), “Statement on the Conclusion of U.S.-Korea (Korus) FTA Meetings in Seoul,” Press Release, January 2018, https://ustr.gov/about-us/policy-offices/press-office/fact-sheets/2018/january/statement-conclusion-us-korea-korus.

[2] Charles Boustany and Richard J. Ellings, “China and the Strategic Imperative for the United States,” Asia Policy 13, no. 1, (2018): 48.

[3] World Bank, World Integrated Trade Solution Database, https://wits.worldbank.org. This collection of data is based on a similar chart published by the U.S. Chamber of Commerce. See Tami Overby, “We Need to Get Back into the Trade Game in Asia,” U.S. Chamber of Commerce, June 6, 2017, https://www.uschamber.com/series/modernizing-nafta/we-need-get-back-the-trade-game-asia.

[4] “South Korea—International Trade and Investment Country Facts,” U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA), Fact Sheet, https://www.bea.gov/international/factsheet/factsheet.cfm?Area=626.

[5] Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy (South Korea), “Trade Balance,” http://english.motie.go.kr/en/if/tb/trade/tradeList.do.

[6] Charles Boustany Jr., “Ex-Im Must Be Reauthorized for Small Business to Succeed,” Hill, July 16, 2014, http://thehill.com/opinion/op-ed/212513-ex-im-must-be-reauthorized-for-small-business-to-succeed.

[7] Commission on the Theft of American Intellectual Property, “The Theft of American Intellectual Property: Reassessments of the Challenge and United States Policy,” National Bureau of Asian Research, February 2017, http://www.ipcommission.org/report/IP_Commission_Report_Update_2017.pdf.

[8] “South Korea—International Trade and Investment Country Facts.”

[9] SelectUSA, “Foreign Direct Investment (FDI): South Korea,” U.S. Department of Commerce, Fact Sheet, August 2017, https://www.selectusa.gov/servlet/servlet.FileDownload?file=015t0000000LKNs.

[10] Ju-min Park, “U.S. Washer Tariffs Put Samsung, LG Supply Chains through the Wringer,” Reuters, January 30, 2018, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-trade-samsung/u-s-washer-tariffs-put-samsung-lg-supply-chains-through-the-wringer-idUSKBN1FJ0LZ.

[11] USTR, “Four Year Snapshot: The U.S.-Korea Free Trade Agreement,” Fact Sheet, March 2016, https://ustr.gov/about-us/policy-offices/press-office/fact-sheets/2016/March/Four-Year-Snapshot-KORUS; and USTR, “U.S.-Korea Free Trade Agreement,” https://ustr.gov/trade-agreements/free-trade-agreements/korus-fta.

[12] Ashley Dutta, “KORUS Five Years Later: Triumphs and Challenges,” Washington Council on International Trade, May 15, 2017, http://wcit.org/korus-five-years-later-triumphs-challenges/#_ftnref4.

[13] U.S. Department of Energy, “15 U.S. Code § 717b—Exportation or Importation of Natural Gas; LNG Terminals,” https://www.energy.gov/sites/prod/files/2013/04/f0/2011usc15.pdf.

[14] USTR, “Four Year Snapshot.”

[15] Cho Kye-wan, “South Korea and U.S. Begin Second Round of Negotiations for Amending KORUS FTA,” Hankyoreh, February 2, 2018.

Charles Boustany Jr. is a Counselor at the National Bureau of Asian Research (NBR). Congressman Boustany served in the U.S. Congress from 2005 to 2017 for Louisiana’s 3rd Congressional District and held leadership positions on the House Ways and Means Committee.

Clara Gillispie is Senior Director for Trade, Economics, and Energy Affairs at NBR.