Taiwan's Policy Evolution after the South China Sea Arbitration

Ting-Hui Lin (Taiwan Society of International Law) discusses Taiwan’s policy evolution and adoption of a new policy framework after the South China Sea arbitration.

On July 12, 2016, an arbitral panel constituted under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) delivered its merits and award in the case brought by the Philippines against China over disputed territory in the South China Sea. In response to the decision, Taiwan’s government stated, “We absolutely will not accept the tribunal’s decision and we maintain that the ruling is not legally binding on the ROC [Republic of China].”

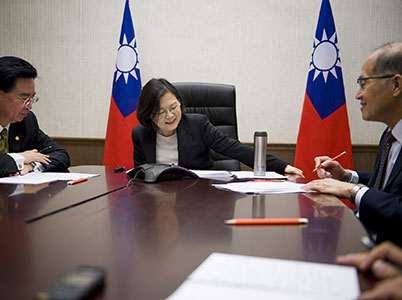

Despite this initial rejection of the ruling, President Tsai Ing-wen approved a new South China Sea policy that does not directly challenge the arbitration decision. This policy is based on four principles—peaceful settlement of disputes in accordance with UNCLOS, inclusion of Taiwan in multilateral mechanisms, freedom of navigation and oversight, and the setting aside of difference to promote joint development—and pursues five actions—to safeguard the rights and safety of Taiwan’s fishermen, to enhance multilateral dialogue with other relevant parties, to invite international scholars to Itu Aba Island (Taiping Island) to conduct scientific research, to develop the island into a base for providing humanitarian aid and supplies, and to encourage more local talent to study maritime law. A key aid, Joseph Wu, formerly secretary-general of the presidential office and now minister of foreign affairs, reiterated these four principles and five actions during a session of the Legislative Yuan, Taiwan’s parliament, on December 14, 2017.

President Tsai Ing-wen delivers her inaugural address. (Creative Commons/Office of the President, Republic of China (Taiwan))

In addition to adopting this new policy framework, the Tsai administration has implemented shifts in its legal positions that further harmonize Taiwan’s approach to the South China Sea dispute with UNCLOS. This essay will examine each of these shifts and draw implications for Taiwan’s policy toward the South China Sea.

ELIMINATION OF “HISTORIC WATERS” AND “HISTORIC TITLES” IN OFFICIAL DOCUMENTS

The first of these shifts involves Taiwan’s approach to its maritime claims. According to the UNCLOS principle that “land dominates the sea,” maritime rights derive from a coastal state’s sovereignty over land. Thus, if Taiwan wishes to claim an exclusive economic zone (EEZ) or continental shelf from islands in the South China Sea, its domestic laws and regulations must concord with this principle. Indeed, Taiwan gradually has eliminated references to historic claims through its legislative process and executive regulations.

If we compare the Tsai administration to its predecessors, this shift becomes clear. In the 1993 Policy Guidelines for the South China Sea, suspended in 2005 during the Chen Shui-bian administration, the first point states that “the South China Sea area within the historic water limit is the maritime area under the jurisdiction of the ROC, in which the ROC possesses all rights and interests.” But in 1998, Taiwan’s Legislative Yuan passed the Law on the Territorial Sea and the Contiguous Zone and the Law on the Exclusive Economic Zone and the Continental Shelf, which are generally consistent with customary international law as reflected in UNCLOS and include no reference to either historic waters or historic titles.

In contrast, the Law on the Exclusive Economic Zone and the Continental Shelf of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) of 1998 states in Article 14 that its provisions shall not affect the historic rights of the PRC. Gao Zhiguo, the Chinese judge at the International Tribunal of the Law of the Sea, and Jia Bing Bing argue that neither historic title nor the law of discovery and occupation can be fundamentally understood in terms of treaty law; instead, they are matters of customary international law. Gao and Jia also consider the relevant provisions of UNCLOS as existing in conjunction with historic rights because the treaty’s preamble states that “matters not regulated by this Convention continue to be governed by the rules and principles of general international law.”

A SHIFTING TERRITORIAL CLAIM

In implementing the Law on the Territorial Sea and the Contiguous Zone in February 1999, Taiwan’s Executive Yuan promulgated the First Set of the Baselines and Outer Limits of the Territorial Sea and the Contiguous Zone of the ROC, which declared that all the islets, reefs, and rocks of the Spratly Islands (known as the Nansha Islands in Chinese) within a traditional U-shaped line were the territories of the ROC. The U-shaped line (or eleven-dash line) was defined in the first set of baseline regulations in 1999 to represent title to the islands and other insular features over which the ROC has sovereignty.

Legislative Yuan of the Republic of China in Taipei, Taiwan. (Creative Commons/Wikimedia)

The Tsai administration has stated that “the ROC is entitled to all rights over the South China Sea Islands and their relevant waters in accordance with international law and the law of the sea.” Two points are important in this formulation. First, the phrase “the law of the sea” is inclusive of both UNCLOS and customary international law. Second, the administration has made its claim more ambiguous by using the formulation “South China Sea Islands,” which is a departure from previous governments’ practice of listing the four island groups (the Spratly Islands, Paracel Islands, Macclesfield Bank, and Pratas Islands). This ambiguity opens the door to future adjustments of the claim. One such adjustment might be to bring the claim into better alignment with international law. For example, because Macclesfield Bank is a low-tide elevation, it cannot be separately claimed as the territory of any state. Instead, the Tsai administration has stated that the South China Sea Islands are claimed in accordance with international law.

Although the Tsai administration has not clarified its definition of the South China Sea Islands, its behavior provides some insights. When the USS Hopper destroyer sailed within 12 nautical miles of Scarborough Shoal on January 17, 2018, China protested and accused the United States of trespassing through its territorial waters. However, unlike past administrations, the Tsai government did not protest or react to this event, even though it has declared a territorial sea baseline for Scarborough Shoal and its domestic laws stipulate that foreign military or government vessels shall give prior notice before their passage through the territorial sea of the ROC. In other words, if the Tsai administration sees Scarborough Shoal as part of the South China Sea Islands, protesting and asking foreign military vessels to give prior notice to Taiwan’s government would become a necessity.

“RELEVANT WATERS”: THE SAME WORDS, DIFFERENT MEANINGS

In adopting the terminology of “the South China Sea Islands and their relevant waters” to replace “the South China Sea Islands and their surrounding waters,” the ROC government has for the first time opted to use the same language as the PRC. In its note verbale to the United Nations Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS) responding to Vietnam’s submission of a continental shelf claim beyond 200 nautical miles in the South China Sea, the PRC claims that it “enjoys sovereign rights and jurisdiction over the relevant waters as well as the seabed and subsoil thereof.”

However, this statement should not be understood as referring to the same maritime zones as Taiwan’s use of this language. Under UNCLOS, a coastal state enjoys sovereign rights in its EEZ and over its continental shelf. Thus, if the Tsai administration intends to claim maritime rights in accordance with UNCLOS, the relevant waters around the South China Sea Islands would be limited to the EEZ and continental shelf. Nonetheless, the Tsai administration has not made this position fully clear.

Former President Ma visits Itu Aba Island (Taiping Island). (Creative Commons/Office of the President, Republic of China (Taiwan))

A DIVERGENCE OF OBJECTIONS AGAINST ARBITRATION

China tried to ignore the arbitration decision and declared that the final award was null and void. Taiwan’s government also dismissed any decisions that undermine the rights of the ROC as having no legally binding force. Yet although Taiwan and China seem to maintain similar positions, in fact they have different reasons for rejecting the decision as nonbinding. Taiwan objected to being treated as part of China as well as to the tribunal’s finding that Itu Aba Island (Taiping Island) has no right to claim an EEZ, all while offering Taiwan no formal avenue to participate in the proceedings. However, the Tsai administration did not deny the legitimacy of the arbitral panel. Instead, the presidential office issued a statement noting that the arbitrators had rendered their award in the case brought by the Philippines under UNCLOS, thereby indicating the government’s recognition of the panel’s legality.

Taiwan is a democratic country and subject to the rule of law. The shifts in its maritime legislation and rhetoric demonstrate that Taiwan no longer advocates historic rights in the South China Sea and is willing to abide by international law and UNCLOS in its sovereignty and sovereign rights claims. If all claimants respect the rule of law, securing peace and stability will be possible in the South China Sea.

Ting-Hui Lin is the Deputy Secretary General of the Taiwan Society of International Law.

Download a pdf version of this analysis piece here.

Banner Image: © Office of the President, Republic of China (Taiwan).